Part 2: Helsinki, Finland to Dubrovnik, Croatia

|

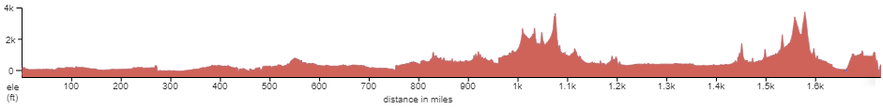

Introduction. In the absence of any established friends along Part 2 of Europa 360, I relied on opportunity whilst I listened to my body to ultimately conclude on where I'd take much needed rest days to conquer the massive and diverse geospatial landscapes between Helsinki and Dubrovnik including the Carpathian Mountains and the Dinaric Alps. Readers will find a complete elevation profile, and stats, for Part 2 to the right and (or) below along with highlights from sections that I had in mind as I rode Part 2 of Europa 360.

|

Dates: 28 September to 16 October (19 days)

Distance: 1,731 miles (2,785 kilometers), 91/108 miles per day including/excluding 3 rest days. Distance and miles per day include a ca. 54 mile (87 km) ferry crossing of the Gulf of Finland from Helsinki to Talinna, Estonia. Climbing: 39,553 (12,056 meters) GPS Details: https://ridewithgps.com/trips/116296582 |

Helsinki to Poland: I rolled-out of Vantaa well before sunrise, making my way, with a persistently runny nose, south to a city I'd last visited in 2009 when I took advantage of proximity, otherwise in Europe to volunteer in Italy and Malta for the Committee Against Bird Slaughter, to go on walking tours of Rome, Herculaneum, Pompeii, and the Amalfi coast, before dropping in on my friend Anna for a one week tour of Finland including Helsinki. Those were fond, crisp memories, which flooded into my consciousness as the sun filtered back into the sky, filling in spaces lit by dim, city lights or none at all. From my 2009 experience, I recalled the Helsinki waterfront in particular, its historic and immaculate character, and conveniently that's where I was headed to catch my next ferry boat to officially set Part 2 of Europa 360 in motion.

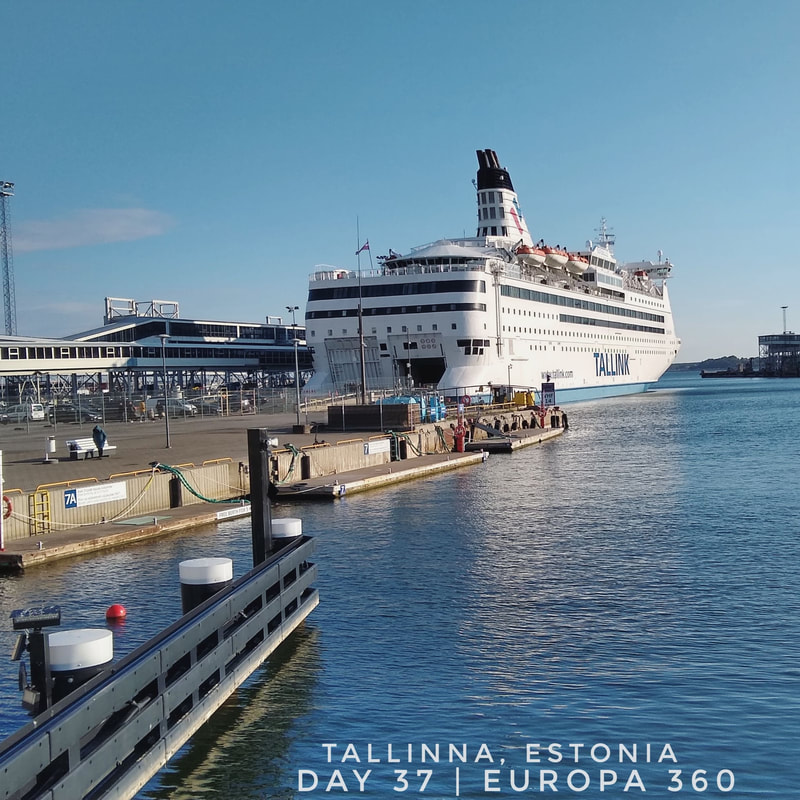

Approaching ferry boats on a bicycle and eventually riding into their vast innards, takes some getting used to, including their steel decks and the often sharp transitions over bridges, etc, that are used to load vehicles and bicycles onto the ship. And even worse, I think, is the associated uneasiness that I sometimes experience, I feel as if I am a lilliputian fully visible in a giant's world, amidst cranes and forklifts and loaded trucks and a ship that dwarfs all of it and especially my light, carbon fiber touring bike. Intimidation is real, even if danger is minimal, nonetheless the friendly chat that I had with the man responsible, that day, for loading the vehicles was a welcome assurance, and my heart rate no doubt settled down, that I would survive one more ship boarding on this tour.

I was en route to Tallinn, which by now I'd grown used to pronouncing like "tal en ah" from conversations with Anna. The Estonian capital was a short sail, directly south across the Gulf of Finland, about two hours and forty miles, from Helsinki. In my heart, I was feeling a mix of curiosity and caution as I approached the Baltic states for the first time in my life. I was also inspired to think about Saint Petersburg, a city I had hoped to visit on this tour prior to the invasion of Ukraine. In those earlier drafts of the tour, instead of taking a ferry boat to Tallinn, I had sketched-out an all-land route from Helsinki to St. Petersburg to Narva, Estonia. As the ship approached the middle of the Gulf, I spent some time leaning over her port rails, on the left side of the ship, in contemplation. Beyond my horizon and far closer than I'd ever been before, Russia, the former Soviet Union, was not far away.

My mind and body slowly warmed-up to the idea of resuming the journey as I made my way onto the first few roads in Tallinn, many of them straight and wide and running along the sea with the town marching upwards on my right. Through tightly packed buildings and confirmed by signage, the oldest district, no doubt formerly walled and otherwise protected, became apparent and as I often do at these junctures I deviated from my route, a bold, purple line staring up at me from my GPS screen, to do some exploring.

The historic significance of this space was all around (video journal update), and in impressive dimensions as the cobbled streets engulfed an ancient hill, climbing and zig-zagging their way to structures that have been here for centuries, back to the Norman Kings in the 12th century and no doubt many more before and after as men fought for the ground under my tires. Rain drizzled at times, and so the light was not fabulous, softening colors and removing shadows, I searched for converging and diverging lines, I always do, and other opportunities to create a worthy representation for myself and my audience, perhaps enough to inspire their own curious mind and adventures.

My extended pause in Tallinn had many effects on my state of mind, all positive and welcome, each one becoming apparent as I transitioned from the city to the countryside, on and off of exceptional bike paths and for the most part, bicycle friendly roads. By now, it was roughly mid-morning and as usual, I still hadn't taken lodging very seriously, only sketched-out the periphery of where I might reach to get a sense of what was possible if I did (or didn't) get that far, a habit I maintained all the way to Dubrovnik, through unfamiliar countries and terrain, for 19 days.

A dry, pine forest with a healthy, dense understory closed in around me and I smiled at my good fortune to be in this far-flung part of the world, risking nothing it turned out, to live a Boston suburb kid's dream of exploring three former states of the Soviet Union, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and much to that kid's surprise, to do it all by bicycle. The ground beneath me, between the old city and Pärnu, on the Gulf of Riga, swelled and flattened and swelled again, never sharply. And for the most part, I made this ca. 80 mile (125 km) transect of the Estonia heartland, through small towns and forests in rotation or conservation, without elevated anxiety, thanks to an absence of high speed hrududus and their kin for most of the journey.

The Gulf of Riga is spectacular in the nearly complete protection, including its outermost buttress, Saaremaa Island, that it provides to its coastal communities, including its namesake Riga, the Capital of Latvia, and Pärnu among them. I approached Pärnu alongside the river that shares its name, until I was kicking up beach sand on paved, coastal roads above Pärnu Bay, adjacent to Pärnu, where I stopped to assess proximate camping options, a process that usually requires about 20 minutes of searching and a few false positives before a suitable, e.g., open and inexpensive ideally, option is found. A few kilometers away, I pitched my tent at the friendly Konse Motel and Caravan Park, where the motel staff suggested and ordered a pizza for me in their native Estonian language and I paid for with my credit card when the delivery service arrived.

For parts or whole of five days, I stuck to the coast and otherwise explored the Baltic states that no longer were just places on a map, places I often paused to explore, wide-eyed with a globe in my hands, in classrooms and libraries in my youth. Two days after departing Helsinki, I rolled into Latvia from Estonia at Ainaži; and two days later, a few kilometers south of Blankenfelde, Latvia, I began my exploration of Lithuania, a complete transect of all three countries that ultimately concluded at the Polish border town, as nightfall was approaching, of Budzisko.

The coastal forests, including former dunes that by now are all but hidden by plant communities that moved into the area since the conclusion of the last glacial maximum (Pleistocene epoch), of all three Baltic countries were similar in character, including forest type, ground cover, and soil. As were the coastal communities, many of which inspired me to imagine that those communities would be an enviable, peaceful, exceptionally clean, and friendly place to raise children or live into a person's golden age.

The infrastructure, even when it was at its most uncomfortable from the perspective of a bike saddle and the pace of passing vehicles, was also well put together, seemingly a priority of all levels of governments in these countries from high speed roadways to village sidewalks. These are impressive spaces to explore, from the perspective of natural history or anthropology, by any means and no doubt many more treasures abound in the inner reaches of all three former, Baltic states that I was unable to sample on my ambitious Europa 360 bicycle tour.

In this video journal update, I offer thoughts and a visual introduction to a typical coastal, conservation area, Kabli Nature Preserve on the Gulf of Riga in Estonia. My explorations in these countries were not always comfortable, thanks to strong opposing or cross-winds, high speed roads that I was unable to avoid at times, and rough forest two-tracks. This video, recorded in Laņi, Latvia; and this one, from Šapnagiai, Lithuania capture a wide swath of those challenges but anyone curious to learn more should listen to the other videos in my video journal playlist from days 37-41 for many more insights.

For anyone curious about how I handled logistics, on this tour and others, including food and lodging this video journal update, from Kunioniai, Lithuania, will be helpful. I want to thank the owners of Sunny Nights Camping and Hostel (Gataučiai, Lithuania), for sharing their wonderful facility with me, a late season guest that was also given the privilege to sleep in the owners, cozy and dry caravan for no extra cost! That kindness aside, I'd still easily rank this experience, their facilities, etc, inside of my top three list from Europa 360. Several locals including the clerk at the nearby, village grocery store are also fond memories.

Approaching ferry boats on a bicycle and eventually riding into their vast innards, takes some getting used to, including their steel decks and the often sharp transitions over bridges, etc, that are used to load vehicles and bicycles onto the ship. And even worse, I think, is the associated uneasiness that I sometimes experience, I feel as if I am a lilliputian fully visible in a giant's world, amidst cranes and forklifts and loaded trucks and a ship that dwarfs all of it and especially my light, carbon fiber touring bike. Intimidation is real, even if danger is minimal, nonetheless the friendly chat that I had with the man responsible, that day, for loading the vehicles was a welcome assurance, and my heart rate no doubt settled down, that I would survive one more ship boarding on this tour.

I was en route to Tallinn, which by now I'd grown used to pronouncing like "tal en ah" from conversations with Anna. The Estonian capital was a short sail, directly south across the Gulf of Finland, about two hours and forty miles, from Helsinki. In my heart, I was feeling a mix of curiosity and caution as I approached the Baltic states for the first time in my life. I was also inspired to think about Saint Petersburg, a city I had hoped to visit on this tour prior to the invasion of Ukraine. In those earlier drafts of the tour, instead of taking a ferry boat to Tallinn, I had sketched-out an all-land route from Helsinki to St. Petersburg to Narva, Estonia. As the ship approached the middle of the Gulf, I spent some time leaning over her port rails, on the left side of the ship, in contemplation. Beyond my horizon and far closer than I'd ever been before, Russia, the former Soviet Union, was not far away.

My mind and body slowly warmed-up to the idea of resuming the journey as I made my way onto the first few roads in Tallinn, many of them straight and wide and running along the sea with the town marching upwards on my right. Through tightly packed buildings and confirmed by signage, the oldest district, no doubt formerly walled and otherwise protected, became apparent and as I often do at these junctures I deviated from my route, a bold, purple line staring up at me from my GPS screen, to do some exploring.

The historic significance of this space was all around (video journal update), and in impressive dimensions as the cobbled streets engulfed an ancient hill, climbing and zig-zagging their way to structures that have been here for centuries, back to the Norman Kings in the 12th century and no doubt many more before and after as men fought for the ground under my tires. Rain drizzled at times, and so the light was not fabulous, softening colors and removing shadows, I searched for converging and diverging lines, I always do, and other opportunities to create a worthy representation for myself and my audience, perhaps enough to inspire their own curious mind and adventures.

My extended pause in Tallinn had many effects on my state of mind, all positive and welcome, each one becoming apparent as I transitioned from the city to the countryside, on and off of exceptional bike paths and for the most part, bicycle friendly roads. By now, it was roughly mid-morning and as usual, I still hadn't taken lodging very seriously, only sketched-out the periphery of where I might reach to get a sense of what was possible if I did (or didn't) get that far, a habit I maintained all the way to Dubrovnik, through unfamiliar countries and terrain, for 19 days.

A dry, pine forest with a healthy, dense understory closed in around me and I smiled at my good fortune to be in this far-flung part of the world, risking nothing it turned out, to live a Boston suburb kid's dream of exploring three former states of the Soviet Union, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and much to that kid's surprise, to do it all by bicycle. The ground beneath me, between the old city and Pärnu, on the Gulf of Riga, swelled and flattened and swelled again, never sharply. And for the most part, I made this ca. 80 mile (125 km) transect of the Estonia heartland, through small towns and forests in rotation or conservation, without elevated anxiety, thanks to an absence of high speed hrududus and their kin for most of the journey.

The Gulf of Riga is spectacular in the nearly complete protection, including its outermost buttress, Saaremaa Island, that it provides to its coastal communities, including its namesake Riga, the Capital of Latvia, and Pärnu among them. I approached Pärnu alongside the river that shares its name, until I was kicking up beach sand on paved, coastal roads above Pärnu Bay, adjacent to Pärnu, where I stopped to assess proximate camping options, a process that usually requires about 20 minutes of searching and a few false positives before a suitable, e.g., open and inexpensive ideally, option is found. A few kilometers away, I pitched my tent at the friendly Konse Motel and Caravan Park, where the motel staff suggested and ordered a pizza for me in their native Estonian language and I paid for with my credit card when the delivery service arrived.

For parts or whole of five days, I stuck to the coast and otherwise explored the Baltic states that no longer were just places on a map, places I often paused to explore, wide-eyed with a globe in my hands, in classrooms and libraries in my youth. Two days after departing Helsinki, I rolled into Latvia from Estonia at Ainaži; and two days later, a few kilometers south of Blankenfelde, Latvia, I began my exploration of Lithuania, a complete transect of all three countries that ultimately concluded at the Polish border town, as nightfall was approaching, of Budzisko.

The coastal forests, including former dunes that by now are all but hidden by plant communities that moved into the area since the conclusion of the last glacial maximum (Pleistocene epoch), of all three Baltic countries were similar in character, including forest type, ground cover, and soil. As were the coastal communities, many of which inspired me to imagine that those communities would be an enviable, peaceful, exceptionally clean, and friendly place to raise children or live into a person's golden age.

The infrastructure, even when it was at its most uncomfortable from the perspective of a bike saddle and the pace of passing vehicles, was also well put together, seemingly a priority of all levels of governments in these countries from high speed roadways to village sidewalks. These are impressive spaces to explore, from the perspective of natural history or anthropology, by any means and no doubt many more treasures abound in the inner reaches of all three former, Baltic states that I was unable to sample on my ambitious Europa 360 bicycle tour.

In this video journal update, I offer thoughts and a visual introduction to a typical coastal, conservation area, Kabli Nature Preserve on the Gulf of Riga in Estonia. My explorations in these countries were not always comfortable, thanks to strong opposing or cross-winds, high speed roads that I was unable to avoid at times, and rough forest two-tracks. This video, recorded in Laņi, Latvia; and this one, from Šapnagiai, Lithuania capture a wide swath of those challenges but anyone curious to learn more should listen to the other videos in my video journal playlist from days 37-41 for many more insights.

For anyone curious about how I handled logistics, on this tour and others, including food and lodging this video journal update, from Kunioniai, Lithuania, will be helpful. I want to thank the owners of Sunny Nights Camping and Hostel (Gataučiai, Lithuania), for sharing their wonderful facility with me, a late season guest that was also given the privilege to sleep in the owners, cozy and dry caravan for no extra cost! That kindness aside, I'd still easily rank this experience, their facilities, etc, inside of my top three list from Europa 360. Several locals including the clerk at the nearby, village grocery store are also fond memories.

Across Poland to Oświęcim: In fading light, under grey skies, and on a busy roadway, I crossed the border from Lithuania into Poland, threading a needle between Russia's Kaliningrad Oblast to the west and a Russian aggression, sympathetic Belarus government to the east. As the initial hills of an extensive, Polish hill country replaced relatively flat ground on the other side of the border, prevailing visualizations replayed in my mind of remote villages locked in timelessness embedded in expansive stretches of agricultural wilderness; a cycling experience on the periphery of modern humanity and perhaps still rooted in preindustrial times.

Those heavily weighted, Bayesian priors lodged somewhere in my frontal cortex, turned-out to be quite good as predictions for simulations yet to come to my proximate here and now. But neither visualization nor consistency between 'priors and data' prepared me for the heart felt depth and admiration that I would plunge into over the next six days, a 600 mile journey, to the outskirts of Krakow, the former Nazi concentration camp, Auschwitz, and the Carpathian Mountains where I would make my next geopolitical transition, to Slovakia, a complete north to south transect of the beautiful country of Poland.

There was no border, a familiar, open European Union scenario. But there certainly had been, not far from Lithuania, on my route, that was now a massive construction site amidst Soviet-era infrastructure that seemed abandoned but had not yet fallen down. The usual construction had to be navigated, torn up roads, sometimes loose gravel, sharp edges, among them; and all whilst dodging trucks of all sizes including semi-tractor trailers. At the conclusion of this trial, I was relieved to find a space to safely pull over and give way to a truck that had been close to my rear tire for a kilometer or more. The occupant waved, beeped, and smiled, as far as I could gauge through dusty, sweaty sunglasses, and it has ever since been a fond memory.

There were quite a few rooms nearby, of the motel, hostel, and pension variety, I stopped at one location along the way but its proximity to the nearby roadway in particular encouraged me to ride-on to Suwalki where I managed, after quite a bit of waiting and discussion before the Ukrainian house manager arrived, to rent a room for about twenty Euro, cash, at Hostel Texas. Those complications withstanding, I enjoyed all of the characters that were involved, their kindness and good intentions were never in doubt or short supply including my housemate Robert (shown in the thumbnail preview of this video journal update), a polish truck driver at that time and father that I established a connection with on Facebook.

Not long after my thoughtful, neutralized roll-out the next morning, my Polish experience truly began as I gradually transitioned east, still traveling primarily south, of the main traffic artery that connects Krakow to Warsaw and Warsaw to the Lithuanian border where I'd crossed the day before. Out here, on the periphery, where Jim Morrison was wrong about the stars, for there were plenty in the evenings that I viewed from camps and other spaces that I migrated to, in all cases by a wonderful myriad of chances including geography, turns in the road, and conversations that despite knowing no Polish at all, or any other language that I encountered crossing 18 countries in 84 days from Barcelona to Barcelona, did not distract the outcome from positive, well intended kindness.

After my first day in the wilderness of eastern Poland, where I was on and off of enviable agricultural and forest gravel tracks with few breaks on asphalt to recover and find resources such as food, I found myself closing in on a large town, for the area where I'd been traveling. Wizna sits safely above, on the west bank of the meandering, deeply entrenched but seemingly, based on it's wide and unencumbered plain, flood prone Narew River. I'd been following that river, on the same side, for many miles and occasionally getting my tires into the water and wetlands drained by its tributaries. The community has a population size ca. 1300 and is the namesake of the 1939, Battle of Wizna, a realization of the opening assault by Germany into the Republic of Poland.

Despite the chances of arriving here, feeling the way I did, tired as a soldier from the retreating, 1939 Polish army, somehow that's what had unfolded and now amidst Wizna's small footprint, a town square that encompassed one block, a small central park, the local police station, pharmacy, and a few more shops, I was contemplating making this village my home for the next two nights to get some much needed, proper rest. Wizna was a Goliath when compared to many of the villages that I visited throughout the day, including Łojki, Pluty, and Sieburczyn, population sizes ca. 80, 130, and so few it hasn't been published, respectively; and it's grocery stores (plural!) and other shops would be welcomed additions to any rest day.

This is how I came to rest, my first break after riding 600 miles in 6 days from Helsinki, hosted by three women, a grandmother, mother, and granddaughter, at the unusually named (for an English speaker) U Wileńskich guest house for ca. 35$ a night. The first two spoke loving kindness with their eyes and gestures but only Polish with their words. However, the granddaughter was an English master. Her mother quickly reached her by cell and handed the phone to me. Like Robert back in Suwalki, the granddaughter and I established a connection for our perpetuity on popular social media apps.

For the next two days (video journal update), I primarily stayed put, catching up on many tour-related tasks, or went whilst always under the watchful care of these ladies, especially the grandmother. In a shop nearby, I replaced a pair of readers that I'd unintentionally ejected somewhere on a forest track. On each of the two nights, as supper approached, I wandered to the nearest grocery shop, across the street, and bought food without concern for weight and other consequences, a blissful realization of the otherwise mundane that I thoroughly enjoyed.

More of Poland's remote countryside, a wilderness other than the presence of agriculture, forest tracks in rotation, and wee villages persisted on the 44th day of the tour, a day shy of the midpoint of my 90 day, allowable, EU stay in any 180 day period. Occasionally, the land rose into a small set of, otherwise, monolithic hills that I climbed in awareness, using breath and other aspects of my meditation practice to keep at bay the minds terrible habit of flooding consciousness with the source of all true suffering.

I crossed the Narew for the last time at Podnarew, bidding my new friend farewell, as I had the Meuse in Namur, Belgium, making my way south towards Warsaw; and in Brok (video journal update), I was introduced to another drainage, another friend on this of tour of countless cherished memories, similar in character to the Narew. On the south side of the Bug River, I crossed the expansive Rezerwat Przyrody Mokry Jegiel nature preserve and its beating heart, the village of Sadowne, by now in east-central Poland.

Those experiences were repeated many times on my trajectory to a suburb of Warsaw where I tucked my tent and bicycle into an enclosed and gated camping facility, shaded by a few magnificent trees that reminded me of ponderosa pines. A bar, restaurant, showers of course, and a kitchen for guests were all included with the entrance fee and I celebrated by having a rare, bar-side draft of beer (or two) on the tour.

It had been another long day, another 100+ miles in my legs, when I rolled into camp, and I spent part of the night and the next morning trying to decide if I would ride into Warsaw or not. When the analysis concluded, I chose to continue south and months later still have no regrets. There is simply no way a cyclist, on a 90 day tour, through eighteen countries can explore every urban center they approach. On this tour, I sacrificed the slow downs associated with going into and out of Warsaw to continue southward progress towards my goals. Hopefully I'll return someday and preferably on a walking tour of that famous city, without the navigational challenges that are associated with city touring by bicycle.

Unbeknownst to me, a sign of deep fatigue no doubt, and despite my often expressed, admiration for rivers, I was surprised to discover that I was not far, when I set out the next morning, to the Vistula, Poland's longest river and an impressive 9th, overall in Europe. I took an extended pause on the Anna Jagiellonka South Bridge overlooking the Warsaw cityscape with the Vistula River below, to behold and capture the scene, using still and video photography, and somewhere along the way triggered acquisition of a fond memory from the tour.

With the Vistula at my back, but soon farther and farther to the east, beyond the horizon over my left shoulder, it was time to ride on which I did for the next two days (video journal update), by now heading southwest, towards Oświęcim, the village that is home to the former, notorious for their cruelty and extensive extinguishing of life, Nazi concentration camps I and II, Auschwitz-Birkenau. I split the ca. 200 mile (320 km) ride, primarily through the same inspired and rural spaces that I'd navigated elsewhere in Poland, into two days, resting at the clean, comfortable, and friendly Hostel Eldorado, part-way, in Końskie.

Before I descend into the sadness of Auschwitz-Birkenau and my visit, I want to conclude this portion of my travelogue, which could easily stand alone as a book chapter if I was to recall the complete story, by highlighting a few of my encounters with local people: a shop owner that surprised me with a coffee as I was otherwise taking shelter from a hot, afternoon sun in her covered garden, not far from a kitten, that was playing below the shops doorstep and otherwise making me a bit anxious (video journal update); the covy of ladies that watched me with curiosity and concern as I rode directly into a marsh where the roads quickly turned to tractor tracks, sometime flooded, sometimes deeply trenched with muddy tracks; the people that I caught a glimpse of amidst their hand tools, weathered, wooden sheds, and gardens, all of it an assemblage of museum artifacts that remain as much in use today as they were centuries ago.

I cherished those brief glances and months later still do, between carefully cultivated fruit trees, among them a woman resting on a bench that didn't seem to notice me as I passed by or perhaps she was already reading my open heart with no ill intentions of her own. I want to thank each one of them for showing me where we have been and how much we have deviated from what's good for our happiness and overall wellbeing as a species. Because of these and other complex, often interwoven, collections of experiences, my journey across Poland was a highlight of my cycling adventures to date. This video journal update from day 46 of the tour, recalls highlights of the tour from the Lithuanian border to Oświęcim where the video was recorded on a sandy gravel track.

Those heavily weighted, Bayesian priors lodged somewhere in my frontal cortex, turned-out to be quite good as predictions for simulations yet to come to my proximate here and now. But neither visualization nor consistency between 'priors and data' prepared me for the heart felt depth and admiration that I would plunge into over the next six days, a 600 mile journey, to the outskirts of Krakow, the former Nazi concentration camp, Auschwitz, and the Carpathian Mountains where I would make my next geopolitical transition, to Slovakia, a complete north to south transect of the beautiful country of Poland.

There was no border, a familiar, open European Union scenario. But there certainly had been, not far from Lithuania, on my route, that was now a massive construction site amidst Soviet-era infrastructure that seemed abandoned but had not yet fallen down. The usual construction had to be navigated, torn up roads, sometimes loose gravel, sharp edges, among them; and all whilst dodging trucks of all sizes including semi-tractor trailers. At the conclusion of this trial, I was relieved to find a space to safely pull over and give way to a truck that had been close to my rear tire for a kilometer or more. The occupant waved, beeped, and smiled, as far as I could gauge through dusty, sweaty sunglasses, and it has ever since been a fond memory.

There were quite a few rooms nearby, of the motel, hostel, and pension variety, I stopped at one location along the way but its proximity to the nearby roadway in particular encouraged me to ride-on to Suwalki where I managed, after quite a bit of waiting and discussion before the Ukrainian house manager arrived, to rent a room for about twenty Euro, cash, at Hostel Texas. Those complications withstanding, I enjoyed all of the characters that were involved, their kindness and good intentions were never in doubt or short supply including my housemate Robert (shown in the thumbnail preview of this video journal update), a polish truck driver at that time and father that I established a connection with on Facebook.

Not long after my thoughtful, neutralized roll-out the next morning, my Polish experience truly began as I gradually transitioned east, still traveling primarily south, of the main traffic artery that connects Krakow to Warsaw and Warsaw to the Lithuanian border where I'd crossed the day before. Out here, on the periphery, where Jim Morrison was wrong about the stars, for there were plenty in the evenings that I viewed from camps and other spaces that I migrated to, in all cases by a wonderful myriad of chances including geography, turns in the road, and conversations that despite knowing no Polish at all, or any other language that I encountered crossing 18 countries in 84 days from Barcelona to Barcelona, did not distract the outcome from positive, well intended kindness.

After my first day in the wilderness of eastern Poland, where I was on and off of enviable agricultural and forest gravel tracks with few breaks on asphalt to recover and find resources such as food, I found myself closing in on a large town, for the area where I'd been traveling. Wizna sits safely above, on the west bank of the meandering, deeply entrenched but seemingly, based on it's wide and unencumbered plain, flood prone Narew River. I'd been following that river, on the same side, for many miles and occasionally getting my tires into the water and wetlands drained by its tributaries. The community has a population size ca. 1300 and is the namesake of the 1939, Battle of Wizna, a realization of the opening assault by Germany into the Republic of Poland.

Despite the chances of arriving here, feeling the way I did, tired as a soldier from the retreating, 1939 Polish army, somehow that's what had unfolded and now amidst Wizna's small footprint, a town square that encompassed one block, a small central park, the local police station, pharmacy, and a few more shops, I was contemplating making this village my home for the next two nights to get some much needed, proper rest. Wizna was a Goliath when compared to many of the villages that I visited throughout the day, including Łojki, Pluty, and Sieburczyn, population sizes ca. 80, 130, and so few it hasn't been published, respectively; and it's grocery stores (plural!) and other shops would be welcomed additions to any rest day.

This is how I came to rest, my first break after riding 600 miles in 6 days from Helsinki, hosted by three women, a grandmother, mother, and granddaughter, at the unusually named (for an English speaker) U Wileńskich guest house for ca. 35$ a night. The first two spoke loving kindness with their eyes and gestures but only Polish with their words. However, the granddaughter was an English master. Her mother quickly reached her by cell and handed the phone to me. Like Robert back in Suwalki, the granddaughter and I established a connection for our perpetuity on popular social media apps.

For the next two days (video journal update), I primarily stayed put, catching up on many tour-related tasks, or went whilst always under the watchful care of these ladies, especially the grandmother. In a shop nearby, I replaced a pair of readers that I'd unintentionally ejected somewhere on a forest track. On each of the two nights, as supper approached, I wandered to the nearest grocery shop, across the street, and bought food without concern for weight and other consequences, a blissful realization of the otherwise mundane that I thoroughly enjoyed.

More of Poland's remote countryside, a wilderness other than the presence of agriculture, forest tracks in rotation, and wee villages persisted on the 44th day of the tour, a day shy of the midpoint of my 90 day, allowable, EU stay in any 180 day period. Occasionally, the land rose into a small set of, otherwise, monolithic hills that I climbed in awareness, using breath and other aspects of my meditation practice to keep at bay the minds terrible habit of flooding consciousness with the source of all true suffering.

I crossed the Narew for the last time at Podnarew, bidding my new friend farewell, as I had the Meuse in Namur, Belgium, making my way south towards Warsaw; and in Brok (video journal update), I was introduced to another drainage, another friend on this of tour of countless cherished memories, similar in character to the Narew. On the south side of the Bug River, I crossed the expansive Rezerwat Przyrody Mokry Jegiel nature preserve and its beating heart, the village of Sadowne, by now in east-central Poland.

Those experiences were repeated many times on my trajectory to a suburb of Warsaw where I tucked my tent and bicycle into an enclosed and gated camping facility, shaded by a few magnificent trees that reminded me of ponderosa pines. A bar, restaurant, showers of course, and a kitchen for guests were all included with the entrance fee and I celebrated by having a rare, bar-side draft of beer (or two) on the tour.

It had been another long day, another 100+ miles in my legs, when I rolled into camp, and I spent part of the night and the next morning trying to decide if I would ride into Warsaw or not. When the analysis concluded, I chose to continue south and months later still have no regrets. There is simply no way a cyclist, on a 90 day tour, through eighteen countries can explore every urban center they approach. On this tour, I sacrificed the slow downs associated with going into and out of Warsaw to continue southward progress towards my goals. Hopefully I'll return someday and preferably on a walking tour of that famous city, without the navigational challenges that are associated with city touring by bicycle.

Unbeknownst to me, a sign of deep fatigue no doubt, and despite my often expressed, admiration for rivers, I was surprised to discover that I was not far, when I set out the next morning, to the Vistula, Poland's longest river and an impressive 9th, overall in Europe. I took an extended pause on the Anna Jagiellonka South Bridge overlooking the Warsaw cityscape with the Vistula River below, to behold and capture the scene, using still and video photography, and somewhere along the way triggered acquisition of a fond memory from the tour.

With the Vistula at my back, but soon farther and farther to the east, beyond the horizon over my left shoulder, it was time to ride on which I did for the next two days (video journal update), by now heading southwest, towards Oświęcim, the village that is home to the former, notorious for their cruelty and extensive extinguishing of life, Nazi concentration camps I and II, Auschwitz-Birkenau. I split the ca. 200 mile (320 km) ride, primarily through the same inspired and rural spaces that I'd navigated elsewhere in Poland, into two days, resting at the clean, comfortable, and friendly Hostel Eldorado, part-way, in Końskie.

Before I descend into the sadness of Auschwitz-Birkenau and my visit, I want to conclude this portion of my travelogue, which could easily stand alone as a book chapter if I was to recall the complete story, by highlighting a few of my encounters with local people: a shop owner that surprised me with a coffee as I was otherwise taking shelter from a hot, afternoon sun in her covered garden, not far from a kitten, that was playing below the shops doorstep and otherwise making me a bit anxious (video journal update); the covy of ladies that watched me with curiosity and concern as I rode directly into a marsh where the roads quickly turned to tractor tracks, sometime flooded, sometimes deeply trenched with muddy tracks; the people that I caught a glimpse of amidst their hand tools, weathered, wooden sheds, and gardens, all of it an assemblage of museum artifacts that remain as much in use today as they were centuries ago.

I cherished those brief glances and months later still do, between carefully cultivated fruit trees, among them a woman resting on a bench that didn't seem to notice me as I passed by or perhaps she was already reading my open heart with no ill intentions of her own. I want to thank each one of them for showing me where we have been and how much we have deviated from what's good for our happiness and overall wellbeing as a species. Because of these and other complex, often interwoven, collections of experiences, my journey across Poland was a highlight of my cycling adventures to date. This video journal update from day 46 of the tour, recalls highlights of the tour from the Lithuanian border to Oświęcim where the video was recorded on a sandy gravel track.

Auschwitz-Birkenau: The ability to feel sympathy for another living organism and especially as this applies to human-to-human interactions, in essence to detect and appreciate the emotional well being of others, is known as empathy in the English language. Narcissists for example, famously lack empathy, as they otherwise go about their day-to-day seemingly locked in a continuous focus that never deviates from their own needs and desires. But despite the harm that narcissists might be responsible for, especially the worst cases of that condition, elsewhere on the spectrum of this empathy disorders far worse outcomes can occur.

Whether or not the motivation comes from a sociopath or a psychopath, cases of the first being unaware of their lack of empathy disorder and the second being aware and denying their condition to the outside world, either case can generate outcomes involving other living organisms that seem to the majority of us, each bound by a strong sense of empathy, to be unfathomably cruel. Cases from my own life that easily come to mind include the famous serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, whose gruesome, unfathomable crimes certainly suggest a lack of empathy towards other human beings. Whether or not that man and others like him lacked empathy or not I cannot say, but there is no doubt that a lack of empathy could explain, in part, why crimes that seem unfathomable to the empathy-bound observer ever occur.

It is estimated that over a million lives were extinguished at Auschwitz, the majority of them at Camp II, Auschwitz-Birkenau, a camp that was designed for mass murder and on a scale that, to my knowledge, has no close comparison from recorded history. I entered the Auschwitz experience, as most do, at Auschwitz I, a former Polish army barracks that was converted to a prisoner of war camp shortly after the Nazi army captured Poland in 1939. By 1940, the camp had many more occupants, and also "functionaries", notorious prisoner guards that were responsible for epic cruelty to other prisoners. Elsewhere in the horror of these and other Nazi concentration camps, only the Nazi SS oversaw the gas chambers including those established at Auschwitz-I in 1941 and Auschwitz-Birkenau (camp II) in 1942.

"It wasn't this way when the camps were in operation", I reminded myself as I walked between the buildings of Auschwitz-I, on a thick bed of grass below the shade of gorgeous, autumn foliage bursting outwardly from oversized trees, each one taking advantage of their unnatural environment, absorbing bountiful light and soil nutrients in the absence of competitors. The original, red-brick constructed buildings, despite their morbid past, also shone in the glory of careful maintenance and elicited a touch of melancholy, in remembrance of the former glory of vanishing construction techniques involving fine craftsman and raw materials.

As part of the overall museum at Auschwitz I-II, many of the buildings (or "blocks") at Auschwitz-I have been converted to museums of different types and purposes. I made my way, guided by an Auschwitz educator, from one to the next. On display were mounds of shoes, formerly worn by children that were forced to strip down prior to heading into a gas chamber disguised as a shower. Once inside, Zyklon B, a cyanide-based pesticide, was deposited into the chambers from above, through vents in the ceiling. The suffering that followed defies imagination, and perhaps that's a good thing for our unchained REM minds.

How it kills is simple in concept, Zyklon B shuts down energy production in our bodies, our bodies can no longer manufacture adenosine triphosphate (ATP). But death is far from instantaneous and imagine how it would feel to experience the simultaneous shutdown of more than 50 trillion cells, each one starving as the oxygen carrying, heme (iron) component of our blood was destabilized. The words don't inspire a comfortable visualization, but apparently the reality was far worse, according to my guide, as all of the fluids normally contained in the human body are ejected outward from a multitude of forces from one epically suffering, violently convulsing human to the next in a dark, crowded chamber of death. Some victims took several minutes to succumb to the poison.

To stand in a gas chamber as I did at Auschwitz-I, or adjacent to the ruined remains of the ovens at Auschwitz-II that were used to hide the crimes, provides no justice for the victims, we cannot bring them back; and we could never, then or now, apply a punishment to the perpetrators that any empathy-feeling being could approve of. Under those constraints, I stood at the places where over one million died and was aware of the crimes and the lives extinguished and I'll never be the same. It was a rare, transformative moment in my life, of the saddest kind.

What happens to me beyond the ground truthing encounters that I had at those camps, e.g., the platforms and the tracks that still lead to the former railway station at Auschwitz-II where so many victims arrived, I cannot say but I am sure that every observation of injustice that I encounter moving forward will be amplified and motivated by those experiences, a modest expression that hopefully will find its way to a sea of many more compassionate observers that when need arises can generate a tsunami wave that dislodges peripheral ideologies that intend to do harm or by their very nature cannot avoid it.

In this extended, video journal update, I reflect on my experience and thoughts from three visits to the camps, over two days, as I was preparing to depart Auschwitz-I for the last time on the tour. And in this video, from inside and outside of the Queen's House, a wonderful, inexpensive guest house in Oświęcim (highly recommend), I provide a lesson in pronunciation of the seemingly unpronounceable Oświęcim and then go into rare detail, for my video journal updates, about many, everyday bike touring topics such as food, laundry, route building and weather.

Whether or not the motivation comes from a sociopath or a psychopath, cases of the first being unaware of their lack of empathy disorder and the second being aware and denying their condition to the outside world, either case can generate outcomes involving other living organisms that seem to the majority of us, each bound by a strong sense of empathy, to be unfathomably cruel. Cases from my own life that easily come to mind include the famous serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, whose gruesome, unfathomable crimes certainly suggest a lack of empathy towards other human beings. Whether or not that man and others like him lacked empathy or not I cannot say, but there is no doubt that a lack of empathy could explain, in part, why crimes that seem unfathomable to the empathy-bound observer ever occur.

It is estimated that over a million lives were extinguished at Auschwitz, the majority of them at Camp II, Auschwitz-Birkenau, a camp that was designed for mass murder and on a scale that, to my knowledge, has no close comparison from recorded history. I entered the Auschwitz experience, as most do, at Auschwitz I, a former Polish army barracks that was converted to a prisoner of war camp shortly after the Nazi army captured Poland in 1939. By 1940, the camp had many more occupants, and also "functionaries", notorious prisoner guards that were responsible for epic cruelty to other prisoners. Elsewhere in the horror of these and other Nazi concentration camps, only the Nazi SS oversaw the gas chambers including those established at Auschwitz-I in 1941 and Auschwitz-Birkenau (camp II) in 1942.

"It wasn't this way when the camps were in operation", I reminded myself as I walked between the buildings of Auschwitz-I, on a thick bed of grass below the shade of gorgeous, autumn foliage bursting outwardly from oversized trees, each one taking advantage of their unnatural environment, absorbing bountiful light and soil nutrients in the absence of competitors. The original, red-brick constructed buildings, despite their morbid past, also shone in the glory of careful maintenance and elicited a touch of melancholy, in remembrance of the former glory of vanishing construction techniques involving fine craftsman and raw materials.

As part of the overall museum at Auschwitz I-II, many of the buildings (or "blocks") at Auschwitz-I have been converted to museums of different types and purposes. I made my way, guided by an Auschwitz educator, from one to the next. On display were mounds of shoes, formerly worn by children that were forced to strip down prior to heading into a gas chamber disguised as a shower. Once inside, Zyklon B, a cyanide-based pesticide, was deposited into the chambers from above, through vents in the ceiling. The suffering that followed defies imagination, and perhaps that's a good thing for our unchained REM minds.

How it kills is simple in concept, Zyklon B shuts down energy production in our bodies, our bodies can no longer manufacture adenosine triphosphate (ATP). But death is far from instantaneous and imagine how it would feel to experience the simultaneous shutdown of more than 50 trillion cells, each one starving as the oxygen carrying, heme (iron) component of our blood was destabilized. The words don't inspire a comfortable visualization, but apparently the reality was far worse, according to my guide, as all of the fluids normally contained in the human body are ejected outward from a multitude of forces from one epically suffering, violently convulsing human to the next in a dark, crowded chamber of death. Some victims took several minutes to succumb to the poison.

To stand in a gas chamber as I did at Auschwitz-I, or adjacent to the ruined remains of the ovens at Auschwitz-II that were used to hide the crimes, provides no justice for the victims, we cannot bring them back; and we could never, then or now, apply a punishment to the perpetrators that any empathy-feeling being could approve of. Under those constraints, I stood at the places where over one million died and was aware of the crimes and the lives extinguished and I'll never be the same. It was a rare, transformative moment in my life, of the saddest kind.

What happens to me beyond the ground truthing encounters that I had at those camps, e.g., the platforms and the tracks that still lead to the former railway station at Auschwitz-II where so many victims arrived, I cannot say but I am sure that every observation of injustice that I encounter moving forward will be amplified and motivated by those experiences, a modest expression that hopefully will find its way to a sea of many more compassionate observers that when need arises can generate a tsunami wave that dislodges peripheral ideologies that intend to do harm or by their very nature cannot avoid it.

In this extended, video journal update, I reflect on my experience and thoughts from three visits to the camps, over two days, as I was preparing to depart Auschwitz-I for the last time on the tour. And in this video, from inside and outside of the Queen's House, a wonderful, inexpensive guest house in Oświęcim (highly recommend), I provide a lesson in pronunciation of the seemingly unpronounceable Oświęcim and then go into rare detail, for my video journal updates, about many, everyday bike touring topics such as food, laundry, route building and weather.

Oświęcim to Budapest, Hungary: Despite all that I'd seen in Poland so far, I was still unprepared to predict what I would encounter as I approached and rode into the Carpathians for the first time in my life. Poland extends into the northern third of that range, eventually giving way to far more of the Carpathians in adjacent Ukraine and Slovakia. The High Tatras or Tatra Mountains, a famous range in the western Carpathians, provide a natural border between Poland and Slovakia.

I chose the drainage of the Soła, the same river that runs through Oświęcim on its way to the Vistula, as my access point into the Carpathians. Climbing began at Porąbka and a series of climbs followed, each one comfortably spaced by a flat stretch of road overlooking expansive reservoirs. As I ascended these opening climbs, the distant, High Tatras, snow covered and beckoning adventures like myself as sirens do for the the sailers she hunts, became a familiar feature of the skyline over my left shoulder.

In between, in this far southern region of Poland, villages clung to hillsides that were otherwise a patchwork of pastures and forests that collectively generated a scene reminiscent of the stunning vistas of the Swiss Alps that I'd first encountered on my 2016, 7 countries in 16 days bicycle tour. The Carpathians, at this juncture, certainly didn't match the scale of the Swiss Alps but that didn't detract much from the similarity and the powerful affect the setting had on my central nervous system. Farther along, ski resorts abounded, as they would have in the same setting in Switzerland. Up close, as I rolled through one village after another, the architecture reminded me of another region in the Alps, Austria, wood construction finished in soft reds, blues, and yellows and often accented by prominent window planters and flowers.

Above the largest of three reservoirs, at the village of Żywiec, I left the Soła and enjoyed a short-lived reprieve from climbs to Korbielów where the road pitched up again and continued this way to a pass and the Slovakian border where I paused for worship (video journal update). Not far away, a man traveling by motorcycle did the same. There were few structures here, and a modest parking area, conveniently located close to the EU border sign that marked the transition between Slovakia and Poland.

By now I'd ridden into cool air, held a little longer in the morning by dense, towering pines, and a myriad of small drainages protected under their foliage. On my naked skin, I felt an uncomfortable chill but I knew from previous experience that at the pace I would subsequently descend the coolness wouldn't last long and so I settled into my breath and focused on gratitude as I glided my loaded bicycle along many enviable twists and bends, eventually over a few more ascents, and ultimately to a palatial reservoir, formed by a dam on the Polhoranka river, on the western end of an extensive intermontane valley.

Not far away, to the west, I could have easily ridden back into Poland, but I turned east and resumed the patience that I had been cultivating all morning, as I initiated the next climb. Like the col at the border crossing, this one ascended to about 2700 feet, a gradual climb to a prominent pass between higher ground a few kilometers south of Hruštín, a village in the Námestovo District, Žilina Region of northern Slovakia. I paused at the top of this climb for reflection (video journal update), by chance finding an enviable vantage, down a short gravel track that led to the upper slopes of a massive meadow, much of it seemingly in hay production.

The subsequent descent, more like a plummet from the Heavens, more or less concluded at Oravský Podzámok, at the impressive, clear and fast flowing Orava River that seemed unimpeded by the debris that had fallen down from the surrounding mountains for millennia. Instead, the river churned and pounded its passengers, of all sizes, patiently turning sharp-edged stones into smooth river cobbles that so many of us enjoy picking up and rolling in our hands and sometimes putting in our pockets as a fond memento.

I left the stones in the river on the 49th day of my bicycle journey and my reward, or so it seemed, was an encounter with the meticulously cared for Orava Castle. Built on a crag overlooking the Orava and not long after the Mongols invaded Hungary in 1241 CE, the view from it's parapets and towers must be truly extraordinary. At this juncture, there are high, forested mountains all around, only broken by the stalwart Orava River where, on both banks, craftsmen have plied their craft in exquisite stone work and other, preferred building modalities from a former age. The setting is fabulous, from any perspective, even from below which is the closest advance that I could allocate on a journey as ambitious as Europa 360.

I took advantage, whilst in the route building phase of this portion of my tour (in Oświęcim), to allow myself to glide along, moving downstream with the Orava, for many kilometers, knowing that by this juncture in the day, following one climb after another, my legs would appreciate the gentle assistance of the river. Above her banks, enviable villages amplified the gratitude I was already feeling, each one accented with dots and dashes and their kin in ways that overwhelmed my language training but I nonetheless attempted to pronounce with my inner voice as, e.g., signs with the Slovak places names Široká, Kňažia, and Záskalie came into view.

My vigil with the river and its quaint, inviting villages concluded at Dolný Kubín where I turned south, into another drainage, part of the watershed of the Orava, the Váh, and the Danube that drains into the Black Sea hundreds of miles east of my southward trajectory. Beyond the next summit, my third ascent to 2400+ feet in a day, I easily descended into the largest town in my tour so far of Slovakia, Ružomberok.

By then I'd developed a significant hunger, which I was hoping to satisfy with a trip to a local grocery store. When that search didn't conclude well, it was after all past midday on a Sunday, I "settled" for a pizza shop but not before I went exploring in Ružomberok's old town center, expertly laid pavers gently encouraged tourists to move according to geometric lines, towards ice cream shops and shaded benches and a cornucopia of retail sellers.

This time of day, the Váh could not be heard above the street sounds. Nonetheless, it wasn't far away and no doubt creating a cacophony of pleasant noise, twenty four hours a day and night, soothing to anyone close by, just beyond a window, in the darkness when stillness prevailed and machinery took a break. For the town and its neighbors, the Váh created a natural border to invading armies coming from the north and also solo, wandering cyclist that intended no harm to anyone. But from the perspective of the river, it was here for no reason other than to capture the Revúca, at the juncture that I went searching for to initiate my most significant ascent in the Carpathians, nearly into the Alpine zone and by its conclusion, also well inside of the deep chill that comes to those high spaces in October.

Among those external forces that inspire my adventurous spirit is a muse that beckons me to mountain tops, where timeless fractured stone and the lichens that cling to them await the few that go there, above the dens of little beast that sing on its weathered, scree slopes. I had not sensed the presence of this familiar muse as I began to drift into a flow state, between forest patches in gorgeous autumn color, on either side of the Revúca, following a dedicated bicycle path, sometimes paved but often surfaced in crushed stone.

Farms and their infrastructure came and went, comforting and modest, taking only what they needed and often giving much more. And each kilometer more, the Revúca grew louder, the sun sank a little lower, and my meditation deepened. Unaware of the ruse and satisfied beyond words, I was feeling true bliss despite fatigue from a massive journey over 49 days and its consequences for my mind and body.

Where the bike trail ended, so too did, inconveniently for my safety and navigational convenience, the majority of light that I could see by, beyond the capacity of my Sinewave Beacon headlight powered by a Son 28 dynamo hub. My meditation was subconsciously put on hold, as I took on one more the warriors task for the journey, to reach the summit at Donovaly where many gravel tracks entered the woods and I would depart the main route for what I anticipated would be a memorable wilderness experience spent alone on a mountain.

Those expectations withstanding, I did pause to consider, when I reached the turn-off glowing on my Garmin 1030 Edge GPS screen, many, nearby off-season lodging opportunities, including Snow Park Donovaly. It's likely, that for no more than 40 Euro, I could have enjoyed a hot meal and a warm bed, perhaps breakfast too, after what had already been a packed day of excitement and physical commitments on my bicycle tour. But instead, a slave to my muse, I rode towards the lonely mountains from the base of Snow Park Donovaly, into the dark.

I had been without water for many kilometers and unwilling to stop, especially on the paved section of fast, though lightly trafficked, road that concluded at the Snow Park. Once back in the woods, and beyond the edges of those recreational areas, the sound of flowing water was a relief to my systems. I couldn't see it, but it was there, as anyone without headphones, something I never use in general, and certainly never when cycling, when my headlight illuminated my quarry, a spring seemingly managed, in part, for adventure seekers like myself. I drank to my satisfaction and a bit more, before filling my bottles. Here's a video journal update that captures that moment in the woods.

I had by chance, routed myself, unnecessarily it turned out, from the spring up a steep, gnarly with tree roots, slope that despite my gratitude at the spring took I took some time to warm-up to as I slipped into a momentary state of discontent. My camp, and the heart of my siren's song, wasn't far away and I suspect I closed that gap, once I topped the short hand over foot trial and relocated the trail, in less than ten minutes.

Up here, in a wide, palatial meadow between forest patches and hardy trees that eek out their lives just below the alpine zone, enough light remained to setup my Big Agnes Fly Creek tent before I had to rely 100% on my Black Diamond, USB rechargeable headlamp for all other tasks, including laying out dinner on newspaper scraps that, I've found, work well for that purpose and can easily be recycled or repurposed as an additional insulating layer above the cyclists heart when descending, etc, through cold air. I was still carrying newspaper that I'd swiped, to use as insulation under my cycling jersey, from a recycle bin in Estonia, the morning that I road out of Pärnu.

Far above Donovaly, my highest ascent in the Carpathians, to over 3400 feet, I laid my bike on the grass and crawled into my tent, already below an enormous sky that was lit by the Milky Way Galaxy's estimated 100 billion suns. I listened eagerly for the sounds of my neighbors, and simultaneously hoped that I'd not dropped any morsels, of cheese or meat in particular, that could attract a bear. Drifting off into sleep, I recall only leaves and branches, from a patch of forest about 100 feet away, rustling in a light wind, already wearing all of my sleeping layers, plus my down jacket, as the temperature quickly plummeted to below freezing.

The next morning, I lay still, and warm, within those layers, for far longer than I otherwise would have. The chill outside was considerable, as my nose and cheeks reported back. I was waiting for the sun to reach my tent, a vigil (video journal update) that I fully realized, eventually, standing and watching as a massive shadow line, cast by a hill to the east of my camp, quickly moved towards my line of longitude.

It was an incredible moment, when a wall of light, photons traveling from our sun through 93 million miles of space at lightspeed crashed into and through my anticipating body. Dressed all in black, not an accident for a light-touring cyclist that has thoughtfully considered the pluses and minuses of not only gear but also their color too, the heat sunk in quickly and like a pika awaiting the same on slopes familiar to me back in Colorado every cell in my body quickly came alive, its mitochondrial, fat burning engines and the processes they fire transformed in an immeasurable instant.

Fifty days had passed since I navigated the infrastructure of busy, Barcelona International Airport, eventually into the Spanish foothills of the Pyrenees, the initiation of a journey that had already been epic for a solo traveler on a carbon fiber bicycle carrying minimal gear and expectations. This morning in the Carpathians, not far from the snow covered High Tatras, added to that experience as much as any other day on the tour, copiously watering eyes and a runny nose withstanding, minor inconveniences that were unavoidable for an aging man standing and grinning beyond the edges of his, a marvel of technology, synthetic puffy coat, at 3500 feet, on a cold, and delicious, autumn morning.

Adorned with the same puffy coat and a second layer of gloves, among other items I normally would have packed away by now even on the coolest mornings, I began the descent towards Slovakia's populated towns and villages in the region. The descent was rough at times, often steep and fast. Below single track that I followed across fragile alpine meadows, I made my way on two-track roads used primarily by heavy machinery to extract lumber. At a particularly messy two-track intersection, deeply rutted, idle machines and stacked lumber all around, and moving quickly, I unknowingly made a left where I should have gone "straight on" as Ann Wilson reminds us to do in Heart's mega-hit song.

The result was a mix of good and not so bad. The not so bad was cutting out a section of forest two-track that I was otherwise looking forward to. The good was a left-turn route that led to a little less dirt but nonetheless quite a bit of enviable exploration alongside fast running creeks, steep walled, forested mountains of straight, towering conifers on either side, and isolated, villages, peppered along narrow, lightly used asphalt roads. In each village, wood smoke struggled to rise into the cold morning atmosphere and instead sunk and drifted, between buildings and fence lines, generating a cozy impression that made me envious of occupants by hearths, some of them no doubt sipping Slovakian čaj.

Beyond Baláže, Priechod, and Selce, I exited into the big town of Banská Bystrica and from there navigated primarily on lightly trafficked roads, often riding for many miles in the absence of any of the mind destabilizing sounds of hrududus and their kin. Throughout the remainder of the day, I was far below the cool upper slopes of the mountains, riding instead over and between smooth domed, monolithic hills, cleared for food production or covered in deciduous forests including European beech and oaks of many varieties.

It was in this space, embedded primarily in the smells and sounds that feed our human souls, and as that implies usher in a harmful, starvation in their absence, that I rode through a border region of Hungary, and then out again, a handful of miles later, unawares. The first border crossing had gone unnoticed during my route building sessions, back in Poland, and almost unnoticed on the ground, only becoming clear when signs warned me that I was riding back into Slovakia from Hungary.

The second, in contrast, was anticipated and unmistakable, it also marked my life's first encounter with the celebrated Danube as I climbed up and onto the impressive Mária Valéria Bridge between Štúrovo, Slovakia and Esztergom, Hungary. From here, what remained as far as significant obstructions, other than distance, to reach Dubrovnik, were the bold, sharp, Dinaric Alps, a monumental series of lightly populated, spirited mountains and valleys, and a relatively inconsequential region of foothills that would accompany me as I closed the remaining gap, the next day, to the most famous city of antiquity on the Danube, Budapest.

I chose the drainage of the Soła, the same river that runs through Oświęcim on its way to the Vistula, as my access point into the Carpathians. Climbing began at Porąbka and a series of climbs followed, each one comfortably spaced by a flat stretch of road overlooking expansive reservoirs. As I ascended these opening climbs, the distant, High Tatras, snow covered and beckoning adventures like myself as sirens do for the the sailers she hunts, became a familiar feature of the skyline over my left shoulder.

In between, in this far southern region of Poland, villages clung to hillsides that were otherwise a patchwork of pastures and forests that collectively generated a scene reminiscent of the stunning vistas of the Swiss Alps that I'd first encountered on my 2016, 7 countries in 16 days bicycle tour. The Carpathians, at this juncture, certainly didn't match the scale of the Swiss Alps but that didn't detract much from the similarity and the powerful affect the setting had on my central nervous system. Farther along, ski resorts abounded, as they would have in the same setting in Switzerland. Up close, as I rolled through one village after another, the architecture reminded me of another region in the Alps, Austria, wood construction finished in soft reds, blues, and yellows and often accented by prominent window planters and flowers.

Above the largest of three reservoirs, at the village of Żywiec, I left the Soła and enjoyed a short-lived reprieve from climbs to Korbielów where the road pitched up again and continued this way to a pass and the Slovakian border where I paused for worship (video journal update). Not far away, a man traveling by motorcycle did the same. There were few structures here, and a modest parking area, conveniently located close to the EU border sign that marked the transition between Slovakia and Poland.

By now I'd ridden into cool air, held a little longer in the morning by dense, towering pines, and a myriad of small drainages protected under their foliage. On my naked skin, I felt an uncomfortable chill but I knew from previous experience that at the pace I would subsequently descend the coolness wouldn't last long and so I settled into my breath and focused on gratitude as I glided my loaded bicycle along many enviable twists and bends, eventually over a few more ascents, and ultimately to a palatial reservoir, formed by a dam on the Polhoranka river, on the western end of an extensive intermontane valley.

Not far away, to the west, I could have easily ridden back into Poland, but I turned east and resumed the patience that I had been cultivating all morning, as I initiated the next climb. Like the col at the border crossing, this one ascended to about 2700 feet, a gradual climb to a prominent pass between higher ground a few kilometers south of Hruštín, a village in the Námestovo District, Žilina Region of northern Slovakia. I paused at the top of this climb for reflection (video journal update), by chance finding an enviable vantage, down a short gravel track that led to the upper slopes of a massive meadow, much of it seemingly in hay production.

The subsequent descent, more like a plummet from the Heavens, more or less concluded at Oravský Podzámok, at the impressive, clear and fast flowing Orava River that seemed unimpeded by the debris that had fallen down from the surrounding mountains for millennia. Instead, the river churned and pounded its passengers, of all sizes, patiently turning sharp-edged stones into smooth river cobbles that so many of us enjoy picking up and rolling in our hands and sometimes putting in our pockets as a fond memento.

I left the stones in the river on the 49th day of my bicycle journey and my reward, or so it seemed, was an encounter with the meticulously cared for Orava Castle. Built on a crag overlooking the Orava and not long after the Mongols invaded Hungary in 1241 CE, the view from it's parapets and towers must be truly extraordinary. At this juncture, there are high, forested mountains all around, only broken by the stalwart Orava River where, on both banks, craftsmen have plied their craft in exquisite stone work and other, preferred building modalities from a former age. The setting is fabulous, from any perspective, even from below which is the closest advance that I could allocate on a journey as ambitious as Europa 360.

I took advantage, whilst in the route building phase of this portion of my tour (in Oświęcim), to allow myself to glide along, moving downstream with the Orava, for many kilometers, knowing that by this juncture in the day, following one climb after another, my legs would appreciate the gentle assistance of the river. Above her banks, enviable villages amplified the gratitude I was already feeling, each one accented with dots and dashes and their kin in ways that overwhelmed my language training but I nonetheless attempted to pronounce with my inner voice as, e.g., signs with the Slovak places names Široká, Kňažia, and Záskalie came into view.

My vigil with the river and its quaint, inviting villages concluded at Dolný Kubín where I turned south, into another drainage, part of the watershed of the Orava, the Váh, and the Danube that drains into the Black Sea hundreds of miles east of my southward trajectory. Beyond the next summit, my third ascent to 2400+ feet in a day, I easily descended into the largest town in my tour so far of Slovakia, Ružomberok.

By then I'd developed a significant hunger, which I was hoping to satisfy with a trip to a local grocery store. When that search didn't conclude well, it was after all past midday on a Sunday, I "settled" for a pizza shop but not before I went exploring in Ružomberok's old town center, expertly laid pavers gently encouraged tourists to move according to geometric lines, towards ice cream shops and shaded benches and a cornucopia of retail sellers.

This time of day, the Váh could not be heard above the street sounds. Nonetheless, it wasn't far away and no doubt creating a cacophony of pleasant noise, twenty four hours a day and night, soothing to anyone close by, just beyond a window, in the darkness when stillness prevailed and machinery took a break. For the town and its neighbors, the Váh created a natural border to invading armies coming from the north and also solo, wandering cyclist that intended no harm to anyone. But from the perspective of the river, it was here for no reason other than to capture the Revúca, at the juncture that I went searching for to initiate my most significant ascent in the Carpathians, nearly into the Alpine zone and by its conclusion, also well inside of the deep chill that comes to those high spaces in October.

Among those external forces that inspire my adventurous spirit is a muse that beckons me to mountain tops, where timeless fractured stone and the lichens that cling to them await the few that go there, above the dens of little beast that sing on its weathered, scree slopes. I had not sensed the presence of this familiar muse as I began to drift into a flow state, between forest patches in gorgeous autumn color, on either side of the Revúca, following a dedicated bicycle path, sometimes paved but often surfaced in crushed stone.

Farms and their infrastructure came and went, comforting and modest, taking only what they needed and often giving much more. And each kilometer more, the Revúca grew louder, the sun sank a little lower, and my meditation deepened. Unaware of the ruse and satisfied beyond words, I was feeling true bliss despite fatigue from a massive journey over 49 days and its consequences for my mind and body.

Where the bike trail ended, so too did, inconveniently for my safety and navigational convenience, the majority of light that I could see by, beyond the capacity of my Sinewave Beacon headlight powered by a Son 28 dynamo hub. My meditation was subconsciously put on hold, as I took on one more the warriors task for the journey, to reach the summit at Donovaly where many gravel tracks entered the woods and I would depart the main route for what I anticipated would be a memorable wilderness experience spent alone on a mountain.

Those expectations withstanding, I did pause to consider, when I reached the turn-off glowing on my Garmin 1030 Edge GPS screen, many, nearby off-season lodging opportunities, including Snow Park Donovaly. It's likely, that for no more than 40 Euro, I could have enjoyed a hot meal and a warm bed, perhaps breakfast too, after what had already been a packed day of excitement and physical commitments on my bicycle tour. But instead, a slave to my muse, I rode towards the lonely mountains from the base of Snow Park Donovaly, into the dark.

I had been without water for many kilometers and unwilling to stop, especially on the paved section of fast, though lightly trafficked, road that concluded at the Snow Park. Once back in the woods, and beyond the edges of those recreational areas, the sound of flowing water was a relief to my systems. I couldn't see it, but it was there, as anyone without headphones, something I never use in general, and certainly never when cycling, when my headlight illuminated my quarry, a spring seemingly managed, in part, for adventure seekers like myself. I drank to my satisfaction and a bit more, before filling my bottles. Here's a video journal update that captures that moment in the woods.

I had by chance, routed myself, unnecessarily it turned out, from the spring up a steep, gnarly with tree roots, slope that despite my gratitude at the spring took I took some time to warm-up to as I slipped into a momentary state of discontent. My camp, and the heart of my siren's song, wasn't far away and I suspect I closed that gap, once I topped the short hand over foot trial and relocated the trail, in less than ten minutes.

Up here, in a wide, palatial meadow between forest patches and hardy trees that eek out their lives just below the alpine zone, enough light remained to setup my Big Agnes Fly Creek tent before I had to rely 100% on my Black Diamond, USB rechargeable headlamp for all other tasks, including laying out dinner on newspaper scraps that, I've found, work well for that purpose and can easily be recycled or repurposed as an additional insulating layer above the cyclists heart when descending, etc, through cold air. I was still carrying newspaper that I'd swiped, to use as insulation under my cycling jersey, from a recycle bin in Estonia, the morning that I road out of Pärnu.

Far above Donovaly, my highest ascent in the Carpathians, to over 3400 feet, I laid my bike on the grass and crawled into my tent, already below an enormous sky that was lit by the Milky Way Galaxy's estimated 100 billion suns. I listened eagerly for the sounds of my neighbors, and simultaneously hoped that I'd not dropped any morsels, of cheese or meat in particular, that could attract a bear. Drifting off into sleep, I recall only leaves and branches, from a patch of forest about 100 feet away, rustling in a light wind, already wearing all of my sleeping layers, plus my down jacket, as the temperature quickly plummeted to below freezing.

The next morning, I lay still, and warm, within those layers, for far longer than I otherwise would have. The chill outside was considerable, as my nose and cheeks reported back. I was waiting for the sun to reach my tent, a vigil (video journal update) that I fully realized, eventually, standing and watching as a massive shadow line, cast by a hill to the east of my camp, quickly moved towards my line of longitude.