21-29 August 2019

Duncansby Head to Port Ellen, Islay on a Route that Celebrates the Journey

542.9 miles on the bike with 33,081 feet of climbing, equivalent to one ascent up Mount Everest from sea level plus 3000 bonus feet!

Duncansby Head to Port Ellen, Islay on a Route that Celebrates the Journey

542.9 miles on the bike with 33,081 feet of climbing, equivalent to one ascent up Mount Everest from sea level plus 3000 bonus feet!

Left, my route through Scotland from Edinburgh Airport to Waverley Train Station Wick to Duncansby Head, and onward through Scotland ultimately to Port Ellen, Islay, Inner Hebrides, in total 542.9 miles covered on the bike (not including ferry crossings) with 33,081 feet of climbing (a bit more than one trip to the top of Mt Everest from sea level); right-top, taking a moment to absorb the start of my tour at Duncansby Head; and approaching the northwest highlands close to Heilam, Scotland.

By air and rail, I arrived to Wick, Scotland a day earlier than originally planned, on the 20th of August. The next morning I slept in, amassing as much rest as I could after a sleepless vigil on a red-eye flight from Newark the night before. Before departing Wick, I dropped a package to my former girlfriend, to Hamburg, Germany, some things I had already decided I didn’t need. Then I visited an ATM machine, followed by a bike shop to properly air-up my tires. Back at Edinburgh International Airport, the previous day, inside the baggage claim area, I had assembled my bike and then inflated each of my tubeless tires using a hand-pump without a gauge other than my opposing index finger and thumb on my right hand. Before setting off, I was comforted to be able to check my tire pressure before initiating my longest journey to date on a bicycle.

I said goodbye to Brian, the local bike shop owner, at about 11:20 am, made a 180 degree turn, and then glided down a modest hill to a bridge over the River Wick and then back into the village centre, a short stretch of shops on both side of the road where I'd been earlier in the morning to visit an ATM and the post office. At the north end of town, the road turned sharply left then gradually right where it quickly transitioned onto a gently rolling, agricultural landscape.

It was a bit of a shock to my system to be riding on European roads, especially a primary road, the A99, after so much time away from my former winter home in Germany, and of course riding on the left side of the road had to be carefully negotiated for a guy from North America, especially intersections - looking left rather than right might result in a trip to the hospital or worse in the United Kingdom. As I’ve done in the past, whilst riding in the UK, I spoke using my outside voice as I negotiated each intersection, “look right then look left”, moving my head with my words and repeating two or three times. Traffic density on the A99 was moderate, but even worse, most of the cars, lorries, and moto-bikes were intent on getting somewhere as quickly as possible, a lunch reservation perhaps, even if that meant passing a cyclist at high speed on a hill or a corner.

Exiting Wick, I was expecting to find a comfortable secondary road, or ideally a tertiary road such as a tractor track (a variety of surfaces smooth to jarring) or smooth, paved single track. Single track roads are, in general, abundant in Europe including the UK, and collectively they provide an extensive network of one lane roads with pullouts for passing that is ideal for bicycle touring. By chance, in this remote northeast corner of Scotland, where modest Wick was the largest village around and not "large" in any true sense, there was only one road from Wick to John O'Groats, the A99, roughly eighteen miles with only one, brief (a few miles), opportunity to shave off some highway on a combination of single- and tractor-track roads. Quite remarkably, shortly after transitioning onto this exception, which effectively cut a corner off the main road, my rear tire blew completely off the rim. The gauge back in Wick must have been reading lower than reality, enough to blow the tire off the rim in one exciting, messy, and loud explosion. Instantly the sealant that normally sloshed around in my tubeless tire was airborne and then all over me and the bike. Seemingly a tragedy, I instead laughed out loud as I peacefully went to work installing a tube on the road side, all the while feeling grateful that I was by chance off the busy and frenetic A99.

About an hour later, at a junction and a small shop in John O’Groats, I turned right off the A99 and immediately plunged into the peacefulness of single track and easily closed the gap to Duncansby Head, about two miles ahead. When I arrived, I found myself perched high on a hill, amidst many sheep and a few tourists, officially at land's end in northeast Scotland. Whizzing this way and that way through the atmosphere were many old friends, from my days working as a seabird biologist, a type of marine bird known as the northern fulmar; they were nesting on nearby cliffs. Herring gulls and black-legged kittiwakes were also easy to detect by sight and sound. A light tower and house balanced the scene, each perched at the top of the hill a short walk from roads-end and the primary visitor parking area. Below their stone foundations, green pastures descended to the North Sea. To the north, the not-so-distant Orkney Islands were plainly visible on the horizon.

From this spot, and for the next 10-12 weeks, my plan was to pedal from Duncansby Head, first trending west, then south, then east all the way to Istanbul. If 10 weeks wasn't enough, then I had already given myself permission to extend my ticket reservation by as many as four weeks, but for now I anticipated departing Turkey on 28 October using my return 'multi-city' ticket purchased from United and their partner, Turkish Airlines, the same booking that carried bike rider and bike over the Atlantic to Edinburgh.

On the first afternoon of my tour, at Duncansby Head, the universe and its quirky quantum physics was already sending friends my way. Shortly after a young couple kindly used my camera to capture the image of me, with bike, resting on a bench overlooking the Orkney Islands, two couples inquired about my journey and were shocked to hear that my goal was Istanbul. Images followed, for which I was flattered. Bjorn et al. wished me well and soon I was officially on my way.

When a person sets-out to accomplish something difficult inevitable challenges arise, and some of these threaten the outcome of the journey. I was only a half mile or so from Duncansby Head when I discovered that both of the top clips on one of my saddle bags had broken. Fortunately the bag would still hang from the rear rack on the remaining plastic mounts but without some sort of fix the bag would otherwise swing so much that I wouldn’t be able to control the bike. I was carrying cable ties and enough of them to deal with this sort of unwelcome problem, at least temporarily. The bags, from Blackburn Design's Barrier Outpost series, were new when I departed Denver International Airport. It certainly made me a little sad to have this happen at the outset of my tour but I nonetheless had plenty of reserves of energy and motivation to ride on and quickly set any serious concerns aside.

With a second problem in less than twenty miles resolved, I returned to the A99 then quickly transitioned to the A836. Heading west from here, for about twenty-five more or less comfortable miles, I arrived at the biggest town on the north Scottish coast, Thurso, a name with obvious Norse roots (pronounced with a hard T, like "Turso"). I hailed a youngster, then another, until I eventually located a bike shop. Sam and Sean were quick to come to my aid. I wanted to remove the tube and return the bike to a tubeless state. This way I had the maximum number of options for dealing with any punctures. Two tubes, a spare tire, and a patch kit were subsequently back in my Oveja Negra frame bag where I hoped they'd stay, at least until my rear tire was worn down from many miles versus a momentary encounter with a sharp object.

Donald Rumsfeld popularized four categories involving knowns and unknowns. Each of the four would eventually make themselves known on my tour and the first was an "unknown unknown" that likely would have, if not detected by Sean, left me stranded somewhere between Thurso and Durness, where there were no bicycle repair shops. When the bike breaks in places between, like the one just described, the only option is to hitchhike, something I've had to do only one time on all of my bike tours. It turned out that the sudden departure of my tire from its rim was actually serendipitous, because Sean ultimately discovered a few other problems.

Of particular and noteworthy concern, my lower derailleur pulley was completely stripped of all its teeth! Also on the "not so nice" list of unhappy discoveries, my derailleur hanger appeared to be bent, just slightly, a gift from the baggage handlers and likely the reason why my pulley wheel was obliterated. Foolishly, I wasn't carrying a spare hanger on the tour so the existing one would have to be carefully straightened. As Sean searched the shops bins for new pulley wheels that would fit my 11 speed, Ultegra drive-train I waited with nervous anticipation. when he eventually held up my prize I expelled plenty of nervous energy whilst Sean went to work repairing the problem.

I probably spent an hour inside or outside of the shop, possibly a bit more. During this time, I walked to a hardware store and purchased extra large cable ties, sufficient for a more-or-less permanent fix for the broken clips on my pannier. I wouldn’t be able to remove that bag very quickly but the ties were reusable. Jumping ahead, for the remainder of the tour I was able to remove the ties using a small pair of needle-nosed pliers that were part of my kit. And just one pair of these durable, wide, black cable ties survived the entire journey.

Almost giddy with satisfaction that my wheel was back to tubeless and other, previously "unknown unknown" problems were resolved, at least for now, I rode through downtown Thurso in light rain and a strong southerly side wind over my left shoulder as I resumed my trajectory west towards Durness. An intentional late start earlier in the day followed by bike issues set me way back on this opening day of my tour. Nonetheless, I managed a solid block of miles before arriving to what seemed like a sensible village to rest, Bettyhill or Betty’s Hill or Bett’s Hill as I often heard it spoken by the locals. I dropped into the local hotel for a pint, a hot dinner, and to ask about affordable lodging nearby. Fortunately, the hotel was full and so by asking I certainly wasn’t going to offend anyone. The hostess was generous with her smile and her resources. She not only recommended a place but also phoned-up the owner and, once I confirmed my interest, booked me a bed for the evening at Lorna’s Bed & Breakfast, aka, Thistle Cottage.

Lorna’s compound, a collection of buildings intended for sheep, goats, horse, and man, is at the bottom of the hill below the hotel, and just over the River Naver. A short walk away from her compound is a beach where people often camp. Above the beach and adjacent to the buildings, about 100 sheep wander and distribute their droppings with very little intervention. In extensive pastures above the living area, her retired herd of about thirty horses enjoys an enviable life for horse or man. Lorna was formerly an equestrian guide.

Kindred spirits have a way of finding each other, and Lorna was my first, of this variety, for my 2019 autumn cycling tour. Our conversations had no beginning or end, they were seamless, in each case we entered a parallel, pleasurable flow state that neither of us noticed, our introduction took most of an hour. The next morning we resumed with no difficulty as she cooked me breakfast in the space that I had rented from her, formerly the house where she lived with her husband and daughter, presently she’s living in a garden shed close by.

Among the topics I won’t forget, she went into detail about a “leopard” that’s been eating her sheep, a female in her opinion but there is another “leopard”, a male, which also comes to dine from time-to-time. I found the details absolutely convincing, including how the animals arrived to this far away, for the species, outpost – a critical mass, to support reproduction in the wild, of leopards that were illegally kept and eventually released. It’s fascinating to think that such a gigantic and predatory cat is flourishing in the UK. That is, until you come face-to-face with one as you’re exiting your tent for a pee, as could happen on the beach below Lorna’s pastures. Let's hope not.

Fattened and smiling, I headed west from Thistle Cottage the next morning out onto a landscape that was beginning to transition from gently rolling agricultural fields interrupted only by stone walls to low-lying fields separated by the foothills of the approaching northwest highlands. I followed the coast, which sometimes routed me far north and then south, and back again, as I repeatedly plunged into deep fjords and out onto adjacent peninsulas. Those unavoidable features of the coastline withstanding I was nevertheless often riding west with a strong wind between my left shoulder and ear, a struggle but by no means a significant struggle. When I briefly turned south I was brought, in contrast, nearly to a standstill! Followed by a fast, fun, downwind grin that never lasted long enough.

At Heilam, I transitioned from plains to mountains, and fairly quick as I plunged into a valley and then began my first ascent of many. I was now officially in the highlands. At this stage, I also rode into light rain, a premonition of what was to come even though I remained relatively comfortable in the here-and-now on a road that despite being designated an A-road was lightly trafficked and otherwise bike friendly.

Although Durness was just ca. 92 miles from Duncansby Head, it nonetheless was a significant point on my tour, for two reasons, one distant and the other quite proximate. For the tour as a whole, this was the point where I’d turn south, a trajectory that I would subsequently maintain all the way to the town of Lismore in the south of Ireland (where I hoped to meet the famous travel writer and cyclist, Dervla Murphy) before "finally", as anyone following my cross-Europe tour might insert, turning east towards my overall goal for the tour, Istanbul.

The proximate, "in my face" you might say, significance of Durness was that it was here, on a high hill overlooking the turbulent confluence of the Atlantic and the North Sea, that I turned south into a very strong headwind that would, jumping ahead, remain the norm all the way to Lismore, a distance of several hundred miles. Sustained winds were ca. 20 mph with gusts that nearly brought me to a complete stop. And worse, about ten miles south of Durness, as I approached a long climb, the rain began to come down in drenching format. The combination of wind, rain, and cool temperatures stung my naked skin, especially my face. Well before I reached the first pass, I was wet and chilled. However, it was a survival situation I knew well from racing in exposed, alpine, spaces such as the Colorado Trail high above Durango. As I had done in those situations before, I focused on smooth, efficient breathing and pushing back any negative thoughts that my mind generated.

Fortunately, the night before I’d slept well and this contributed, no doubt, to what I was feeling even under such difficult conditions – enthusiasm for the journey. I leaned over the bike as best I could and focused on releasing tension from those parts of my body that I did not need, such as face and shoulders; I told my mind that all was well and I took one step to the left or right, mentally, out of the chaos. From this vantage I watched the storm as if I was outside of the milieu. Using these tricks, I made progress and eventually transitioned, at the top of the pass, into a world that seemingly resided, comfortably, in the upper atmosphere, at cloud level, a world away from where I’d come from in Durness and east of there, and where I was eventually headed. It was an exceptional privilege to feel so much and so early on the tour, on the surface of terra firma in the "high" lands of northwest Scotland.

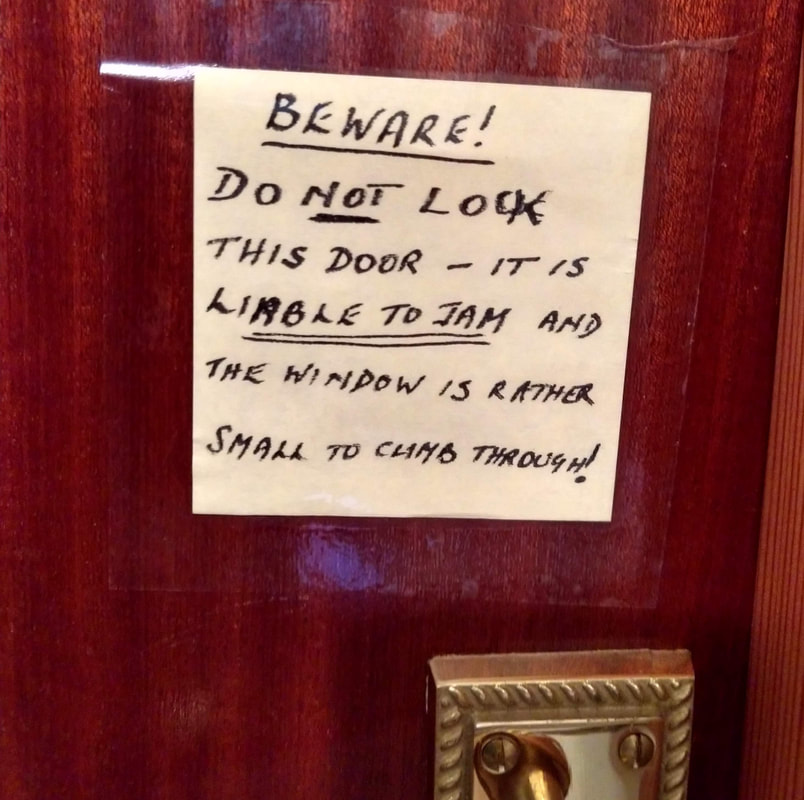

I arrived quite chilled to Kylesku and the hotel of the same name at close to five pm, wearing no clothing at all on my legs and only light gear under my raincoat, nothing more than a wind breaker by this point. Inside, I purchased a hot meal and inquired about lodging at the hotel and budget-friendly, nearby, alternatives. Like the hotel back in Bett's Hill the night before, this place was also full. They offered to let me pitch my bivy in the forest not far from the bar, an idea that sounded pretty good to me before I had a chat, using the Hotel's phone, with Mary, a bnb owner located one mile to the south. By the way, this hotel was nearly the full extent, weeks beyond the busy tourist season, of civilization between Unapool, the location of Mary’s home, and larger Ullapool where I was scheduled to hop on a ferry to Stornoway, Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides (Scotland) the next morning at 9:35 am.

Mary was advanced in age, wisdom, and kindness. She informed me that all her rooms were booked; but then with only a moment of hesitation, said “if you’re stuck” she would make room for me in her living room. Everyone will have a different reference point where unstuck transitions to stuck and those will change from moment-to-moment. At this particular moment, “stuck” for me was a wet forest in a bivy sack following a very difficult day of cycling through rain and wind on top of Scotland’s remote, northwest highlands. After dinner, I closed the gap to Mary’s and settled in as she watched a cricket match and educated me on the details of the game, unfamiliar to a guy that grew up close to Boston, Massachusetts. The couch was far better than the forest above Loch Gleann Dubh and I slept not-so-great but well enough to wake early, about 5 am, eat a quick breakfast, with coffee of course (dreadful instant) and be on my way towards Ullapool.

During the night, the weather had actually worsened. The wind had increased; the rain seemed constant and heavy at times. I walked to the top of Mary’s steep driveway, made my way through the gate, clipped into the bike and accepted my fate as best I could. The next 33 miles were unforgettable, thorough difficult terrain and the worst weather of any of my bike tours. Anticipating that it wouldn’t be a fair weather morning, I’d departed very early, giving myself over three hours to reach the ferry at Ullapool. Normally, I could have managed about 12 mph, maybe a bit more or less, in mountainous terrain. However, this morning I barely managed 10, enough to comfortably arrive, purchase a ticket, and line my sodden bike and body in its designated location at the ferry terminal.

I met a traveler and cyclist in the boarding area, a young fellow from Switzerland that was advanced in all ways except age, and we talked most of the way to Stornoway where we purchased groceries together before going separate ways. Sodden remained the status quo for me, other than the crossing when I put on dry street clothes, but at least my route took me west-northwest across the Isle of Lewis during which I enjoyed a strong push from a southerly wind until I reached the Atlantic Ocean, about 20 miles west of Stornoway. At that point, whilst overlooking the waves running up onto pristine, sandy beaches, and with somewhat dreaded anticipation, I turned south and once again faced a steady 15-20 mph wind with gusts well above 25-30. Fortunately, the rain was intermittent and never heavy.

At Carloway, about twenty miles from the junction that led back to Stornoway, far from where I might have otherwise concluded in the absence of cold, rain, and a cruel wind, I turned into a business area where I by chance found a bench behind the buildings and had a time-out, to clear my head, and replenish a few calories. Nearby, I noticed an open door, and I had noticed a few cars in the parking lot on the way to the bench. I assumed the owners were inside, and friendly. After a makeshift second lunch, I made my way through the open door in search of a local. I not only found that but also a full pot of tea and biscuits! Friendly people are the rule and their kindness, stories, and more, are a big part of what makes a journey so special. I departed about thirty minutes later, by this point already booked into a very unusual hostel, Gearrannan Blackhouse Village, that I never would have found on my own and it wasn’t far away.

The next morning, I was up by 5:30 am and immediately planning, scheming, concluding and subsequently revising potential routes over and over again. I checked the weather and it was more of the same, wind and rain from the south and southwest. By 9 am, a rather insane, certainly unusual, conclusion prevailed: I decided to stay one more night at the hostel, for just 20 quid, and then depart at 3 am the following morning. Weather reports suggested the wind would subside to less than 5 mph and stay this way all the next day. And by mid-day, sunshine through partly cloudy skies was anticipated. All of this did in fact transpire and with it a bike rider that was feeling the elements, and far too early for a long tour, was filled with joy. This feeling of joy that comes following a positive change in the weather was a reminder of why I do what I do, going outside of my comfort zone and beyond, the rewards far outweigh the comfort that comes from otherwise avoiding periods of physical hardship.

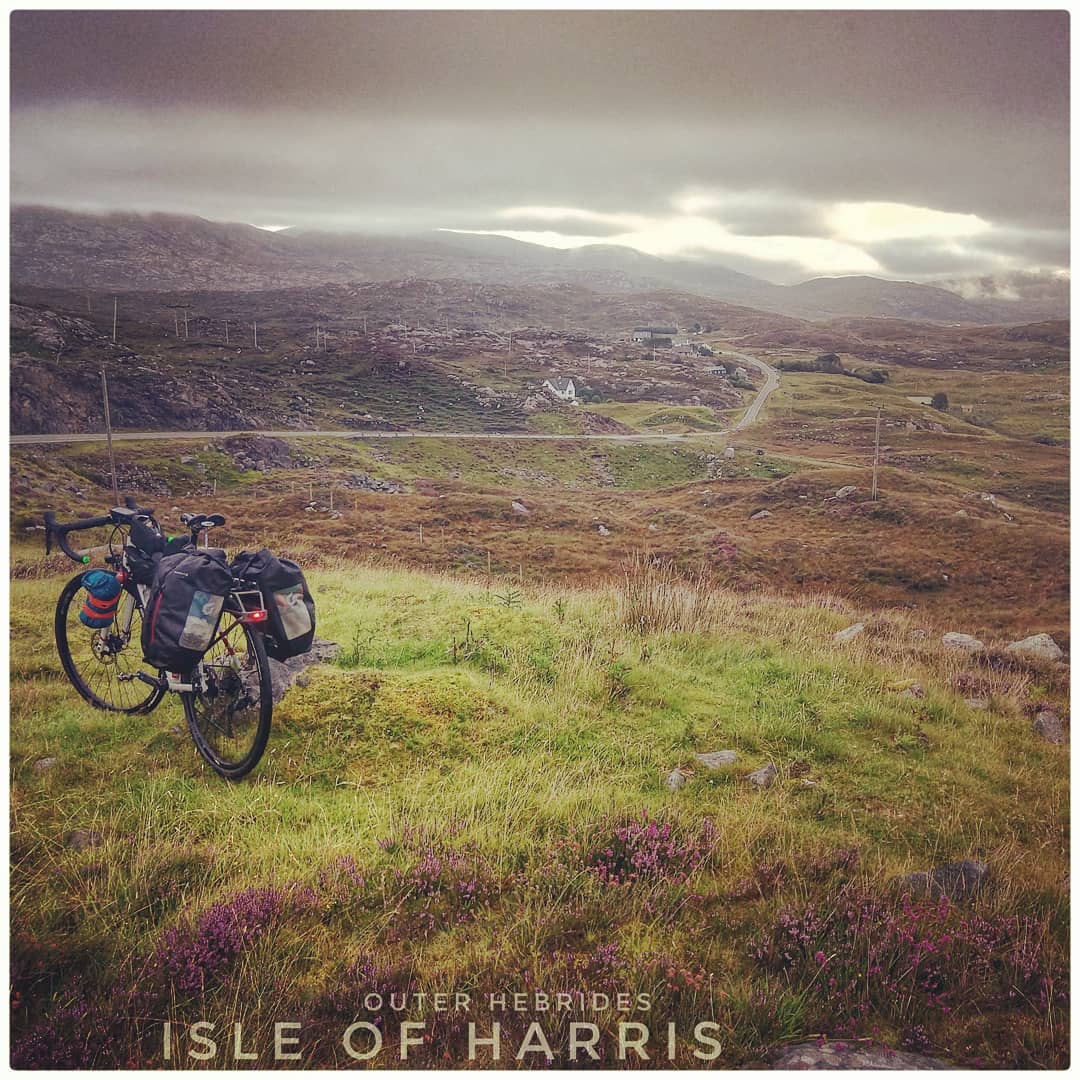

Hours later, as I was passing through the hostel gate, a quick look at my GPS confirmed I was on-schedule, 3:09 am. A few hours later in full darkness other than my headlight, constantly burning bright thanks to my Sinewave dynamo, I stopped at a road-sign that read “Welcome to the Isle of Harris.” Just beyond, I ascended and ascended until I was back in highlands, above the primarily rolling plains of the Isle of Lewis to the north. When I could finally see without lights, I discovered an extension of the misty world that I first encountered, on this tour, in the northwest highlands. I was not alone, sheep were everywhere, and red deer, many with massive and impressive antlers. My Lycra clad body split the clouds as they drifted past. Wonderland was all around and I felt gratitude to have the space nearly all to myself. From Carloway to Harris, I encountered three cars and a van. Not bad for 60-ish miles. My new lightening system from Sinewave worked splendidly, so much so that riding through the night inspired excitement, in my heart, reminiscent of my childhood "swamp" exploration days. Much to my pleasure, there was also neither wind nor rain to negotiate, a much welcome physical reality no doubt shared by my mammalian companions, many of them lying on their sides, on and off the road, content to watch me roll past with partially open eyes.

Beyond these high places and the clouds, I descended much faster than I'd climbed back down to the Atlantic Coast. On the Isle of Harris, I discovered impressive, in part because of their expanse, white sand beaches that with few exceptions were completely empty of any souls. I enjoyed the ride and the view as I made my way, along an otherwise rocky coastline, to my next ferry stop, and the reason for my early departure. I arrived to Leverburgh with time to spare, somewhat unfortunate given the midges were flying, a consequence of a day with very little wind. To avoid the majority of them, I circled the facilities on my bike, creating some wind of my own.

The ferry departed on time, boats rarely drift unlike their bus cousin, and by about 11 am I was in Bereray on North Uist, the next island in my north to south tour of the Outer Hebrides. The character of this island, and South Uist, was completely different from Harris and Lewis. There were isolated and impressive bits of highlands here and there, but otherwise the land rolled gently from coast to coast and the vegetation was predominantly grass, a prairie complex that was very familiar given where I've lived the last ten years on North America's Great Plains. Like Harris, I also encountered extensive white sand beaches, all deserted, on North and South Uist. From Carloway to my destination for the evening, the village of Lochboisdale, I covered a whopping 140 miles not including the ferry crossing. The weather was exceptionally kind to me relative to the previous week. I absorbed the sunshine and a bit of a tailwind as I cranked my Niner Bikes RLT 9 Steel up to an enviable speed and raced across a beautiful landscape created by man and nature.

At Lochboisdale, I arrived to Patsy's Airbnb exhausted despite the good weather and ready to eat anything in sight. As usual, I had stocked-up earlier in the day at a grocery store, enough food for an evening meal and breakfast. The next morning, about a mile from Patsy's home, I loaded onto the Lochboisdale ferry bound for Mallaig, a village where tourists often come to catch a ferry to the Isle of Skye and, in general, a significant cross-roads in the Scottish Highlands. From Mallaig travelers can travel by boat, train, or bus to many locations, near and far, such as Fort William, Oban, and Inverness. Of course, I'd be traveling by other means, the very best in my biased view, by bicycle.

My route from Mallaig to Kilchoan, where I caught a ferry to the Isle of Mull and its hub, Tobermory, was mountainous throughout and spectacularly scenic. Despite the difficulty, about 5000 feet of climbing in 60 miles, it was a fabulous day on the bike, in fine weather. Approaching Kilchoan from the east, not far from Glenbeg, I climbed over a col to the north of Ben Hiant. On all three sides, the sea being the fourth, the landscape below this enchanted mountain was worthy of praise, every shade of green imaginable, a fairyland that easily made its way into my deepest impressions.

A primary effect of all this scenery was a slowing of time, and inside that wormhole a bike and rider slowed as well. On the descent into Kilchoan I laid the bike on the non-drivetrain side and captured many photos of the mountain and its talus slopes, mostly covered in mosses, grasses, and shrubs; in this area I also encountered a large group of touring cyclists, a chase van followed with all of their gear. When I reluctantly reached the Kilchoan ferry dock overlooking a wide inlet, to the south, I had narrowly missed the next ferry to Tobermory. I found a place to hide from some of the wind and enjoyed a couple of apples that I'd found along the roadside, and eventually fell into conversation with travelers from far and wide, including an Italian from Palermo.

As night approached, the next boat arrived and about 30 minutes later I rolled into Tobermory where I simultaneously arrived to the Inner Hebrides for the first time in my life. It was late afternoon by this point, and so I didn't hesitate to go looking for lodging. Quickly I found a hostel, and everything else was close by too, less than a minute walking including restaurants and grocery shops, all of this on the main street, almost literally the only street "in town".

The setting was wonderful, consistent with my hopes, a beautiful village above the sea where homes were often painted with bright colors reminiscent of scenes from Norway and Newfoundland. The marina, adjacent to main street, was a mix of fishing and pleasure boats. Amidst this scenery, I inquired at the Hostel which had just one bed available in a 4-bed, male dorm room for about 25 quid. As usual for my experiences at hostels, I was left feeling like I owed the facility something more when I departed the counter, after paying. This uncomfortable feeling is one of the reasons that I rarely stay in a hostel, a feeling that also hasn't been rewarded with anything special within these compounds, which are also as expensive or more so than a private room and shared bath at a guest house, Airbnb, or similar in the same area. And foremost among my list of complaints at hostels, it's rare that a shared room doesn't have at least one outrageous snorer.

Fortunately, my three roommates were ideal in this case, all of them went to bed by 10 pm and none of them snored! With the window open and the non-street side behind us, I slept better here than I have in any similar situation. Not far away, on the bunk below and across from my own, Lloyd slept well too, and the next morning we met by chance and established a connection that [jumping ahead] lasted beyond the tour. Lloyd coached me on how I might navigate through his part of Ireland, not far from Belfast and Dublin; and he also generously invited me to stay with him when I passed through the area.

The area for storing bikes, open above but otherwise inside the walls of the hostel, was a beautiful, watery garden, where the often overlooked mini-flora, many lichens and mosses, flourished amidst a community of travelers from just about everywhere. The next morning, I rolled my bike down to a more convenient place for packing. Just before I was ready to roll-out Lloyd rejoined me, he was planning a rest day, he wished me well and held the door as I rolled the bike back into the bustle of a much loved village, by locals and tourists. From here I rode directly to the ferry terminal at Craignure, about 20 miles in 1 hour 30 minutes.

When I arrived, I was hoping to quench my desire for coffee. Sadly, a seemingly fabulous option, based on a quick tour, was closed and no other options were available until I boarded the ship. Instead, I made my way to the front of the line where Leo and his bike were waiting, a Russian that's lived in the UK for many years. I don't recall ever meeting a Russian in Europe, and certainly, firsts aside, what followed was the most intimate discussion I've had with a person that grew up in the suburbs of Moscow. As this implies, I enjoyed every minute of his company which extended to the crossing as well, in fact he bought me a coffee once we were on board. At one point, before we boarded the ship, I mentioned to him that I was struggling to keep my travelogue up-to-date because of fatigue and otherwise long days on the bike. His advice was simple, "just ride." Looking ahead, weeks into the tour, far from Craignure, I never forgot this simple suggestion and I was grateful each time I recalled his advice. The crossings from Kilchoan to Tobermory and Craignure to Oban were about the same, distance and time, about thirty minutes, even without a seamless and enjoyable conversation the crossing was quick and soon I was saying goodbye to Leo.

As I departed the ship, I was hoping to get a photo of the famous town, something worth sharing, so I went first in search of an enviable vantage. Not far away I found a small park, about a quarter-acre in size. I made my way through its iron gate and then across a green, cut lawn to the waterside, the park was perched above a modest cliff but still the vantage was pretty good. I snapped a few photos then fell into conversation with a fellow that had apparently, my conclusion anyway, slept on the bench he was sitting on.

He was about my age, long hair and beard, very Scottish, including a genuine friendliness. He told me part of his story, including his ongoing search, after leaving a life of constant work as a fisherman, to make more of a short life. Although we had different ideas about where to go and how to get there, and he wasn't on his way to anywhere by the way, he was just going, we agreed on the underlying reason for embarking: a general discomfort with the standard offered to anyone that embeds, start to finish, into society's normal.

Robert was dressed all in green and browns, his luggage was a bag that he carried over his shoulder, he was dirty, teeth and skin, and wet, but none of that mattered. He was free and that's what he celebrated the most. Like so many meetings with strangers, this meeting was brief, but it was also significant, as many of those short visits tend to be. I never did get a satisfying image of Oban; perhaps my supposed search for a vantage was actually a search for a Robert, in hindsight.

Beyond the park, I followed a route that I assembled the day before. I used single-track to navigate around a portion of the main road that headed south out of town and along the way was passed by a road cyclist clad in Lycra. I caught him on the next climb and we stayed together for a handful of miles. Along the way he asked a lot of questions, I did the same, in the process I learned a few more valuable details about where I was headed and where I'd been. Local knowledge should never be undervalued; it's far richer, for example, than any Google search. Far from Oban, jumping ahead in this story, this fellow would continue to check in with me from time-to-time. Sadly, I've not heard, through my website, from Leo; and certainly, the fate of Robert I will never know.

I didn't realize it at the time, because throughout this day like most others I made plans as the day unfolded including where to stay, but I was on my way to a night in Tarbert, a village very similar to Tobermory where brightly colored buildings from a former fishing heyday are lined-up side-by-side along a quaint waterfront. Typically on my bike tours, I try to book a bed, using a variety of sources but especially Airbnb, between 4 and 5:30 pm. When camping, which I rarely did on this tour, I look for a campsite after six. My route from Oban to Tarbert was as scenic, and through similar terrain, as the day before, an enviable ride by any measure. At times, trapped on the primary road, no smaller routes available in this part of the Highlands, I had to negotiate high speed traffic but it was rarely more than an occasional car or truck. Overall, the experience was peaceful, a route I could easily recommend to just about any cyclist.

Based on recommendations from "D" back on the Isle of Lewis, I was able to avoid a large section of primary road, the A816 between Kilninver and Kilmelford. Instead I took "the scenic route", in truth all of Scotland's Highlands are scenic, which turned out to be far rougher than "D" had suggested. Beyond the paved, fast, single track, from Ardmaddy, where the road ended at a pubic gate, to Degnish I negotiated many more gates on, more significantly, some of the roughest tractor track I've encountered on any of my tours, including some very steep climbs where the road degraded even more, to bedrock and loose gravel. It was only about six miles, but I earned every inch on my steel bike, packed for touring.

When I reached the other side I was grateful for the experience but also relieved to be on a surface that was not constantly threatening the integrity of my tires and rims. the last section was a steep descent with large stones scattered here and there, each of them an awaiting tragedy. I did my best to navigate at a pace that nonetheless inspired me to smile. At the bottom, the road turned hard left, or gentle right. I took the left option onto deeply potholed but otherwise much more favorable paved single track. Nearby, a bench awaited no one but me. I stopped for a memory photo and then continued towards Melfort Village, a charming community on the water that was obviously favored by the sailing community, and nearby eventually rolled back onto the A816.

If not for ferry boats, my advance south out onto a long peninsula that contained Tarbert and the much more well known town of Campbeltown, would have been a very long, and unadvised, out-n-back for a guy that was trying to cycle to Istanbul. Pausing for a moment on that thought, arriving to Tarbert for a guy that was on his way to Istanbul was also not advisable! But on this trip, like my other adventures by boot, boat, motorbike, and, bicycle, I was here to celebrate the journey and with that in mind Tarbert and it's far flung peninsula were excellent places to explore.

A few miles before arriving to Tarbert, I nearly rode directly to the location of my next ferry boat, the village of Kennacraig where I planned to travel by ferry boat to Islay, the southernmost island of the Inner Hebrides, the following morning. Instead, i made a u-turn, thinking about that end-of-day grocery shop for dinner this evening and breakfast tomorrow. It turned out this was a good last minute decision for at least two reasons, lodging in Kennacraig was sparse and there was no food to be had, no grocery shops or restaurants. In contrast, the village of Tarbert, despite its modest proportions, not only had many shops but also a rich history, involving a well preserved remnant of a castle, high above the town, and a story that included Robert the Bruce and other famous characters from Scottish history.

On this evening, I came up short using my favored Airbnb smart phone app. There were options but nothing fit comfortably into my daily travel budget and those that came close were sparse. The best, cheapest, Airbnb option was in Kennacraig but I quickly discovered that the inn keeper was sick and so was not taking guests for the evening. In a setting like Tarbert, a bustling little town, a sensible plan b is always "ask the locals." Soon I was chatting with a man one level above the street, just outside of one of the town's primary fish processing plants. He advised me on some affordable options and also directed me to the best fish and chip shop in town, which didn't open for about another hour.

Unfortunately, his tips all turned out to be either booked or not responsive, ring the bell a few times and no one arrives to greet you. I went back to my smart phone for a deeper search, using Google maps and key words, like "guest house." And also talked to another local. All this led to the Tarbert Hotel, which I feared would be well above my budget. However, I was thrilled when the bar keep said it was 40 or 45 pounds. Not cheap, but certainly comfortable given the day was nearing its conclusion and I had a significant number of miles and hills climbs in my legs since departing Wick.

I stashed my bike in the Hotel's primary storage area, amidst empty kegs and abandoned furniture, an eclectic space inside the walls of the hotel. Then settled into the town, starting with a tour of the castle, then photos as the sun reached its lowest point before dropping below the hills north of town. The photos that transpired were some of the best from the tour, including crisp reflections of the colorful main street on an active fishing harbor below the town. Tarbert was as serendipitous as any town that I arrived to, late in the day, when it was time to find a bed or a piece of ground. I celebrated my good fortune with a pint in the Hotel bar and a fish-n-chip that I brought to my room, so not to offend the kitchen connected to the bar.

It was only five miles, twenty-two minutes of cycling it turned out, to Kennacraig from Tarbert, so close that I was far from "in the zone" before dismounting, purchasing a ticket, and lining-up with about six other bicycles and many more motorbikes, cars, and lorries. I made some more friends as I waited, and our conversations continued on the ship and for a few minutes before I departed into the mist on the other side where I set-off alone en route to Islay's southernmost port, Port Ellen. The ride from Port Askaig, where I crossed to from Kennacraig, to Port Ellen was just twenty miles and most of it was without topography, flat as the name implies. But beyond the road and the valleys that it passed through, the highlands were here as well, rising above the plains on Islay as they had on North and South Uist in the Outer Hebrides, not dominant but still prominent components of this islands geography.

At the outskirts of Port Ellen, I drifted into the first gas station that I encountered, a very small shop with a few items for sale inside. I was hoping to confirm the existence of the ferry that I'd booked on line a day or two before. Although booking and websites gave me confidence, I remained less than 100% convinced that a small boat hauled passengers from Islay to Northern Ireland across the strait south of Port Ellen until the shop owner easily confirmed my inquiry. From here, with directions to the boat, only a mile or less from the gas station, stashed away in my neurons I made my way into town at a very slow pace, stopping for photos and eventually food, bought at a grocery store, and water, bottles filled from the tap at a local pub and two more acquaintances made and established in the process. I arrived early, at least an hour before the boat was scheduled to depart. Early withstanding, I felt there wasn't time to go exploring beyond Port Ellen where I could otherwise have easily visited two famous distilleries, Laphroaig and Lagavulin, two of my favorites among Scottish whiskies.

Islay had a charm, stitched into its open spaces, which I suspect has been the primary source of its attraction for man and beast through the ages, and I have no doubt a small part of my wanderlust will continue to be inspired by that visit until my conclusion on Planet Earth. In the meantime, a long journey requires a commitment to schedules, at least part of the time. And so I made my way from the local pub to a dock and the Kintyre Express well before departure and then settled into conversation with the first mate and then the captain. In my next entry, I'll pick-up the story of my crossing to Ireland, the friends I visited along the way and the journey south from Ballycastle to Lismore and east to Rosslare Harbor, my departure point for the crossing to Wales and England...

I said goodbye to Brian, the local bike shop owner, at about 11:20 am, made a 180 degree turn, and then glided down a modest hill to a bridge over the River Wick and then back into the village centre, a short stretch of shops on both side of the road where I'd been earlier in the morning to visit an ATM and the post office. At the north end of town, the road turned sharply left then gradually right where it quickly transitioned onto a gently rolling, agricultural landscape.

It was a bit of a shock to my system to be riding on European roads, especially a primary road, the A99, after so much time away from my former winter home in Germany, and of course riding on the left side of the road had to be carefully negotiated for a guy from North America, especially intersections - looking left rather than right might result in a trip to the hospital or worse in the United Kingdom. As I’ve done in the past, whilst riding in the UK, I spoke using my outside voice as I negotiated each intersection, “look right then look left”, moving my head with my words and repeating two or three times. Traffic density on the A99 was moderate, but even worse, most of the cars, lorries, and moto-bikes were intent on getting somewhere as quickly as possible, a lunch reservation perhaps, even if that meant passing a cyclist at high speed on a hill or a corner.

Exiting Wick, I was expecting to find a comfortable secondary road, or ideally a tertiary road such as a tractor track (a variety of surfaces smooth to jarring) or smooth, paved single track. Single track roads are, in general, abundant in Europe including the UK, and collectively they provide an extensive network of one lane roads with pullouts for passing that is ideal for bicycle touring. By chance, in this remote northeast corner of Scotland, where modest Wick was the largest village around and not "large" in any true sense, there was only one road from Wick to John O'Groats, the A99, roughly eighteen miles with only one, brief (a few miles), opportunity to shave off some highway on a combination of single- and tractor-track roads. Quite remarkably, shortly after transitioning onto this exception, which effectively cut a corner off the main road, my rear tire blew completely off the rim. The gauge back in Wick must have been reading lower than reality, enough to blow the tire off the rim in one exciting, messy, and loud explosion. Instantly the sealant that normally sloshed around in my tubeless tire was airborne and then all over me and the bike. Seemingly a tragedy, I instead laughed out loud as I peacefully went to work installing a tube on the road side, all the while feeling grateful that I was by chance off the busy and frenetic A99.

About an hour later, at a junction and a small shop in John O’Groats, I turned right off the A99 and immediately plunged into the peacefulness of single track and easily closed the gap to Duncansby Head, about two miles ahead. When I arrived, I found myself perched high on a hill, amidst many sheep and a few tourists, officially at land's end in northeast Scotland. Whizzing this way and that way through the atmosphere were many old friends, from my days working as a seabird biologist, a type of marine bird known as the northern fulmar; they were nesting on nearby cliffs. Herring gulls and black-legged kittiwakes were also easy to detect by sight and sound. A light tower and house balanced the scene, each perched at the top of the hill a short walk from roads-end and the primary visitor parking area. Below their stone foundations, green pastures descended to the North Sea. To the north, the not-so-distant Orkney Islands were plainly visible on the horizon.

From this spot, and for the next 10-12 weeks, my plan was to pedal from Duncansby Head, first trending west, then south, then east all the way to Istanbul. If 10 weeks wasn't enough, then I had already given myself permission to extend my ticket reservation by as many as four weeks, but for now I anticipated departing Turkey on 28 October using my return 'multi-city' ticket purchased from United and their partner, Turkish Airlines, the same booking that carried bike rider and bike over the Atlantic to Edinburgh.

On the first afternoon of my tour, at Duncansby Head, the universe and its quirky quantum physics was already sending friends my way. Shortly after a young couple kindly used my camera to capture the image of me, with bike, resting on a bench overlooking the Orkney Islands, two couples inquired about my journey and were shocked to hear that my goal was Istanbul. Images followed, for which I was flattered. Bjorn et al. wished me well and soon I was officially on my way.

When a person sets-out to accomplish something difficult inevitable challenges arise, and some of these threaten the outcome of the journey. I was only a half mile or so from Duncansby Head when I discovered that both of the top clips on one of my saddle bags had broken. Fortunately the bag would still hang from the rear rack on the remaining plastic mounts but without some sort of fix the bag would otherwise swing so much that I wouldn’t be able to control the bike. I was carrying cable ties and enough of them to deal with this sort of unwelcome problem, at least temporarily. The bags, from Blackburn Design's Barrier Outpost series, were new when I departed Denver International Airport. It certainly made me a little sad to have this happen at the outset of my tour but I nonetheless had plenty of reserves of energy and motivation to ride on and quickly set any serious concerns aside.

With a second problem in less than twenty miles resolved, I returned to the A99 then quickly transitioned to the A836. Heading west from here, for about twenty-five more or less comfortable miles, I arrived at the biggest town on the north Scottish coast, Thurso, a name with obvious Norse roots (pronounced with a hard T, like "Turso"). I hailed a youngster, then another, until I eventually located a bike shop. Sam and Sean were quick to come to my aid. I wanted to remove the tube and return the bike to a tubeless state. This way I had the maximum number of options for dealing with any punctures. Two tubes, a spare tire, and a patch kit were subsequently back in my Oveja Negra frame bag where I hoped they'd stay, at least until my rear tire was worn down from many miles versus a momentary encounter with a sharp object.

Donald Rumsfeld popularized four categories involving knowns and unknowns. Each of the four would eventually make themselves known on my tour and the first was an "unknown unknown" that likely would have, if not detected by Sean, left me stranded somewhere between Thurso and Durness, where there were no bicycle repair shops. When the bike breaks in places between, like the one just described, the only option is to hitchhike, something I've had to do only one time on all of my bike tours. It turned out that the sudden departure of my tire from its rim was actually serendipitous, because Sean ultimately discovered a few other problems.

Of particular and noteworthy concern, my lower derailleur pulley was completely stripped of all its teeth! Also on the "not so nice" list of unhappy discoveries, my derailleur hanger appeared to be bent, just slightly, a gift from the baggage handlers and likely the reason why my pulley wheel was obliterated. Foolishly, I wasn't carrying a spare hanger on the tour so the existing one would have to be carefully straightened. As Sean searched the shops bins for new pulley wheels that would fit my 11 speed, Ultegra drive-train I waited with nervous anticipation. when he eventually held up my prize I expelled plenty of nervous energy whilst Sean went to work repairing the problem.

I probably spent an hour inside or outside of the shop, possibly a bit more. During this time, I walked to a hardware store and purchased extra large cable ties, sufficient for a more-or-less permanent fix for the broken clips on my pannier. I wouldn’t be able to remove that bag very quickly but the ties were reusable. Jumping ahead, for the remainder of the tour I was able to remove the ties using a small pair of needle-nosed pliers that were part of my kit. And just one pair of these durable, wide, black cable ties survived the entire journey.

Almost giddy with satisfaction that my wheel was back to tubeless and other, previously "unknown unknown" problems were resolved, at least for now, I rode through downtown Thurso in light rain and a strong southerly side wind over my left shoulder as I resumed my trajectory west towards Durness. An intentional late start earlier in the day followed by bike issues set me way back on this opening day of my tour. Nonetheless, I managed a solid block of miles before arriving to what seemed like a sensible village to rest, Bettyhill or Betty’s Hill or Bett’s Hill as I often heard it spoken by the locals. I dropped into the local hotel for a pint, a hot dinner, and to ask about affordable lodging nearby. Fortunately, the hotel was full and so by asking I certainly wasn’t going to offend anyone. The hostess was generous with her smile and her resources. She not only recommended a place but also phoned-up the owner and, once I confirmed my interest, booked me a bed for the evening at Lorna’s Bed & Breakfast, aka, Thistle Cottage.

Lorna’s compound, a collection of buildings intended for sheep, goats, horse, and man, is at the bottom of the hill below the hotel, and just over the River Naver. A short walk away from her compound is a beach where people often camp. Above the beach and adjacent to the buildings, about 100 sheep wander and distribute their droppings with very little intervention. In extensive pastures above the living area, her retired herd of about thirty horses enjoys an enviable life for horse or man. Lorna was formerly an equestrian guide.

Kindred spirits have a way of finding each other, and Lorna was my first, of this variety, for my 2019 autumn cycling tour. Our conversations had no beginning or end, they were seamless, in each case we entered a parallel, pleasurable flow state that neither of us noticed, our introduction took most of an hour. The next morning we resumed with no difficulty as she cooked me breakfast in the space that I had rented from her, formerly the house where she lived with her husband and daughter, presently she’s living in a garden shed close by.

Among the topics I won’t forget, she went into detail about a “leopard” that’s been eating her sheep, a female in her opinion but there is another “leopard”, a male, which also comes to dine from time-to-time. I found the details absolutely convincing, including how the animals arrived to this far away, for the species, outpost – a critical mass, to support reproduction in the wild, of leopards that were illegally kept and eventually released. It’s fascinating to think that such a gigantic and predatory cat is flourishing in the UK. That is, until you come face-to-face with one as you’re exiting your tent for a pee, as could happen on the beach below Lorna’s pastures. Let's hope not.

Fattened and smiling, I headed west from Thistle Cottage the next morning out onto a landscape that was beginning to transition from gently rolling agricultural fields interrupted only by stone walls to low-lying fields separated by the foothills of the approaching northwest highlands. I followed the coast, which sometimes routed me far north and then south, and back again, as I repeatedly plunged into deep fjords and out onto adjacent peninsulas. Those unavoidable features of the coastline withstanding I was nevertheless often riding west with a strong wind between my left shoulder and ear, a struggle but by no means a significant struggle. When I briefly turned south I was brought, in contrast, nearly to a standstill! Followed by a fast, fun, downwind grin that never lasted long enough.

At Heilam, I transitioned from plains to mountains, and fairly quick as I plunged into a valley and then began my first ascent of many. I was now officially in the highlands. At this stage, I also rode into light rain, a premonition of what was to come even though I remained relatively comfortable in the here-and-now on a road that despite being designated an A-road was lightly trafficked and otherwise bike friendly.

Although Durness was just ca. 92 miles from Duncansby Head, it nonetheless was a significant point on my tour, for two reasons, one distant and the other quite proximate. For the tour as a whole, this was the point where I’d turn south, a trajectory that I would subsequently maintain all the way to the town of Lismore in the south of Ireland (where I hoped to meet the famous travel writer and cyclist, Dervla Murphy) before "finally", as anyone following my cross-Europe tour might insert, turning east towards my overall goal for the tour, Istanbul.

The proximate, "in my face" you might say, significance of Durness was that it was here, on a high hill overlooking the turbulent confluence of the Atlantic and the North Sea, that I turned south into a very strong headwind that would, jumping ahead, remain the norm all the way to Lismore, a distance of several hundred miles. Sustained winds were ca. 20 mph with gusts that nearly brought me to a complete stop. And worse, about ten miles south of Durness, as I approached a long climb, the rain began to come down in drenching format. The combination of wind, rain, and cool temperatures stung my naked skin, especially my face. Well before I reached the first pass, I was wet and chilled. However, it was a survival situation I knew well from racing in exposed, alpine, spaces such as the Colorado Trail high above Durango. As I had done in those situations before, I focused on smooth, efficient breathing and pushing back any negative thoughts that my mind generated.

Fortunately, the night before I’d slept well and this contributed, no doubt, to what I was feeling even under such difficult conditions – enthusiasm for the journey. I leaned over the bike as best I could and focused on releasing tension from those parts of my body that I did not need, such as face and shoulders; I told my mind that all was well and I took one step to the left or right, mentally, out of the chaos. From this vantage I watched the storm as if I was outside of the milieu. Using these tricks, I made progress and eventually transitioned, at the top of the pass, into a world that seemingly resided, comfortably, in the upper atmosphere, at cloud level, a world away from where I’d come from in Durness and east of there, and where I was eventually headed. It was an exceptional privilege to feel so much and so early on the tour, on the surface of terra firma in the "high" lands of northwest Scotland.

I arrived quite chilled to Kylesku and the hotel of the same name at close to five pm, wearing no clothing at all on my legs and only light gear under my raincoat, nothing more than a wind breaker by this point. Inside, I purchased a hot meal and inquired about lodging at the hotel and budget-friendly, nearby, alternatives. Like the hotel back in Bett's Hill the night before, this place was also full. They offered to let me pitch my bivy in the forest not far from the bar, an idea that sounded pretty good to me before I had a chat, using the Hotel's phone, with Mary, a bnb owner located one mile to the south. By the way, this hotel was nearly the full extent, weeks beyond the busy tourist season, of civilization between Unapool, the location of Mary’s home, and larger Ullapool where I was scheduled to hop on a ferry to Stornoway, Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides (Scotland) the next morning at 9:35 am.

Mary was advanced in age, wisdom, and kindness. She informed me that all her rooms were booked; but then with only a moment of hesitation, said “if you’re stuck” she would make room for me in her living room. Everyone will have a different reference point where unstuck transitions to stuck and those will change from moment-to-moment. At this particular moment, “stuck” for me was a wet forest in a bivy sack following a very difficult day of cycling through rain and wind on top of Scotland’s remote, northwest highlands. After dinner, I closed the gap to Mary’s and settled in as she watched a cricket match and educated me on the details of the game, unfamiliar to a guy that grew up close to Boston, Massachusetts. The couch was far better than the forest above Loch Gleann Dubh and I slept not-so-great but well enough to wake early, about 5 am, eat a quick breakfast, with coffee of course (dreadful instant) and be on my way towards Ullapool.

During the night, the weather had actually worsened. The wind had increased; the rain seemed constant and heavy at times. I walked to the top of Mary’s steep driveway, made my way through the gate, clipped into the bike and accepted my fate as best I could. The next 33 miles were unforgettable, thorough difficult terrain and the worst weather of any of my bike tours. Anticipating that it wouldn’t be a fair weather morning, I’d departed very early, giving myself over three hours to reach the ferry at Ullapool. Normally, I could have managed about 12 mph, maybe a bit more or less, in mountainous terrain. However, this morning I barely managed 10, enough to comfortably arrive, purchase a ticket, and line my sodden bike and body in its designated location at the ferry terminal.

I met a traveler and cyclist in the boarding area, a young fellow from Switzerland that was advanced in all ways except age, and we talked most of the way to Stornoway where we purchased groceries together before going separate ways. Sodden remained the status quo for me, other than the crossing when I put on dry street clothes, but at least my route took me west-northwest across the Isle of Lewis during which I enjoyed a strong push from a southerly wind until I reached the Atlantic Ocean, about 20 miles west of Stornoway. At that point, whilst overlooking the waves running up onto pristine, sandy beaches, and with somewhat dreaded anticipation, I turned south and once again faced a steady 15-20 mph wind with gusts well above 25-30. Fortunately, the rain was intermittent and never heavy.

At Carloway, about twenty miles from the junction that led back to Stornoway, far from where I might have otherwise concluded in the absence of cold, rain, and a cruel wind, I turned into a business area where I by chance found a bench behind the buildings and had a time-out, to clear my head, and replenish a few calories. Nearby, I noticed an open door, and I had noticed a few cars in the parking lot on the way to the bench. I assumed the owners were inside, and friendly. After a makeshift second lunch, I made my way through the open door in search of a local. I not only found that but also a full pot of tea and biscuits! Friendly people are the rule and their kindness, stories, and more, are a big part of what makes a journey so special. I departed about thirty minutes later, by this point already booked into a very unusual hostel, Gearrannan Blackhouse Village, that I never would have found on my own and it wasn’t far away.

The next morning, I was up by 5:30 am and immediately planning, scheming, concluding and subsequently revising potential routes over and over again. I checked the weather and it was more of the same, wind and rain from the south and southwest. By 9 am, a rather insane, certainly unusual, conclusion prevailed: I decided to stay one more night at the hostel, for just 20 quid, and then depart at 3 am the following morning. Weather reports suggested the wind would subside to less than 5 mph and stay this way all the next day. And by mid-day, sunshine through partly cloudy skies was anticipated. All of this did in fact transpire and with it a bike rider that was feeling the elements, and far too early for a long tour, was filled with joy. This feeling of joy that comes following a positive change in the weather was a reminder of why I do what I do, going outside of my comfort zone and beyond, the rewards far outweigh the comfort that comes from otherwise avoiding periods of physical hardship.

Hours later, as I was passing through the hostel gate, a quick look at my GPS confirmed I was on-schedule, 3:09 am. A few hours later in full darkness other than my headlight, constantly burning bright thanks to my Sinewave dynamo, I stopped at a road-sign that read “Welcome to the Isle of Harris.” Just beyond, I ascended and ascended until I was back in highlands, above the primarily rolling plains of the Isle of Lewis to the north. When I could finally see without lights, I discovered an extension of the misty world that I first encountered, on this tour, in the northwest highlands. I was not alone, sheep were everywhere, and red deer, many with massive and impressive antlers. My Lycra clad body split the clouds as they drifted past. Wonderland was all around and I felt gratitude to have the space nearly all to myself. From Carloway to Harris, I encountered three cars and a van. Not bad for 60-ish miles. My new lightening system from Sinewave worked splendidly, so much so that riding through the night inspired excitement, in my heart, reminiscent of my childhood "swamp" exploration days. Much to my pleasure, there was also neither wind nor rain to negotiate, a much welcome physical reality no doubt shared by my mammalian companions, many of them lying on their sides, on and off the road, content to watch me roll past with partially open eyes.

Beyond these high places and the clouds, I descended much faster than I'd climbed back down to the Atlantic Coast. On the Isle of Harris, I discovered impressive, in part because of their expanse, white sand beaches that with few exceptions were completely empty of any souls. I enjoyed the ride and the view as I made my way, along an otherwise rocky coastline, to my next ferry stop, and the reason for my early departure. I arrived to Leverburgh with time to spare, somewhat unfortunate given the midges were flying, a consequence of a day with very little wind. To avoid the majority of them, I circled the facilities on my bike, creating some wind of my own.

The ferry departed on time, boats rarely drift unlike their bus cousin, and by about 11 am I was in Bereray on North Uist, the next island in my north to south tour of the Outer Hebrides. The character of this island, and South Uist, was completely different from Harris and Lewis. There were isolated and impressive bits of highlands here and there, but otherwise the land rolled gently from coast to coast and the vegetation was predominantly grass, a prairie complex that was very familiar given where I've lived the last ten years on North America's Great Plains. Like Harris, I also encountered extensive white sand beaches, all deserted, on North and South Uist. From Carloway to my destination for the evening, the village of Lochboisdale, I covered a whopping 140 miles not including the ferry crossing. The weather was exceptionally kind to me relative to the previous week. I absorbed the sunshine and a bit of a tailwind as I cranked my Niner Bikes RLT 9 Steel up to an enviable speed and raced across a beautiful landscape created by man and nature.

At Lochboisdale, I arrived to Patsy's Airbnb exhausted despite the good weather and ready to eat anything in sight. As usual, I had stocked-up earlier in the day at a grocery store, enough food for an evening meal and breakfast. The next morning, about a mile from Patsy's home, I loaded onto the Lochboisdale ferry bound for Mallaig, a village where tourists often come to catch a ferry to the Isle of Skye and, in general, a significant cross-roads in the Scottish Highlands. From Mallaig travelers can travel by boat, train, or bus to many locations, near and far, such as Fort William, Oban, and Inverness. Of course, I'd be traveling by other means, the very best in my biased view, by bicycle.

My route from Mallaig to Kilchoan, where I caught a ferry to the Isle of Mull and its hub, Tobermory, was mountainous throughout and spectacularly scenic. Despite the difficulty, about 5000 feet of climbing in 60 miles, it was a fabulous day on the bike, in fine weather. Approaching Kilchoan from the east, not far from Glenbeg, I climbed over a col to the north of Ben Hiant. On all three sides, the sea being the fourth, the landscape below this enchanted mountain was worthy of praise, every shade of green imaginable, a fairyland that easily made its way into my deepest impressions.

A primary effect of all this scenery was a slowing of time, and inside that wormhole a bike and rider slowed as well. On the descent into Kilchoan I laid the bike on the non-drivetrain side and captured many photos of the mountain and its talus slopes, mostly covered in mosses, grasses, and shrubs; in this area I also encountered a large group of touring cyclists, a chase van followed with all of their gear. When I reluctantly reached the Kilchoan ferry dock overlooking a wide inlet, to the south, I had narrowly missed the next ferry to Tobermory. I found a place to hide from some of the wind and enjoyed a couple of apples that I'd found along the roadside, and eventually fell into conversation with travelers from far and wide, including an Italian from Palermo.

As night approached, the next boat arrived and about 30 minutes later I rolled into Tobermory where I simultaneously arrived to the Inner Hebrides for the first time in my life. It was late afternoon by this point, and so I didn't hesitate to go looking for lodging. Quickly I found a hostel, and everything else was close by too, less than a minute walking including restaurants and grocery shops, all of this on the main street, almost literally the only street "in town".

The setting was wonderful, consistent with my hopes, a beautiful village above the sea where homes were often painted with bright colors reminiscent of scenes from Norway and Newfoundland. The marina, adjacent to main street, was a mix of fishing and pleasure boats. Amidst this scenery, I inquired at the Hostel which had just one bed available in a 4-bed, male dorm room for about 25 quid. As usual for my experiences at hostels, I was left feeling like I owed the facility something more when I departed the counter, after paying. This uncomfortable feeling is one of the reasons that I rarely stay in a hostel, a feeling that also hasn't been rewarded with anything special within these compounds, which are also as expensive or more so than a private room and shared bath at a guest house, Airbnb, or similar in the same area. And foremost among my list of complaints at hostels, it's rare that a shared room doesn't have at least one outrageous snorer.

Fortunately, my three roommates were ideal in this case, all of them went to bed by 10 pm and none of them snored! With the window open and the non-street side behind us, I slept better here than I have in any similar situation. Not far away, on the bunk below and across from my own, Lloyd slept well too, and the next morning we met by chance and established a connection that [jumping ahead] lasted beyond the tour. Lloyd coached me on how I might navigate through his part of Ireland, not far from Belfast and Dublin; and he also generously invited me to stay with him when I passed through the area.

The area for storing bikes, open above but otherwise inside the walls of the hostel, was a beautiful, watery garden, where the often overlooked mini-flora, many lichens and mosses, flourished amidst a community of travelers from just about everywhere. The next morning, I rolled my bike down to a more convenient place for packing. Just before I was ready to roll-out Lloyd rejoined me, he was planning a rest day, he wished me well and held the door as I rolled the bike back into the bustle of a much loved village, by locals and tourists. From here I rode directly to the ferry terminal at Craignure, about 20 miles in 1 hour 30 minutes.

When I arrived, I was hoping to quench my desire for coffee. Sadly, a seemingly fabulous option, based on a quick tour, was closed and no other options were available until I boarded the ship. Instead, I made my way to the front of the line where Leo and his bike were waiting, a Russian that's lived in the UK for many years. I don't recall ever meeting a Russian in Europe, and certainly, firsts aside, what followed was the most intimate discussion I've had with a person that grew up in the suburbs of Moscow. As this implies, I enjoyed every minute of his company which extended to the crossing as well, in fact he bought me a coffee once we were on board. At one point, before we boarded the ship, I mentioned to him that I was struggling to keep my travelogue up-to-date because of fatigue and otherwise long days on the bike. His advice was simple, "just ride." Looking ahead, weeks into the tour, far from Craignure, I never forgot this simple suggestion and I was grateful each time I recalled his advice. The crossings from Kilchoan to Tobermory and Craignure to Oban were about the same, distance and time, about thirty minutes, even without a seamless and enjoyable conversation the crossing was quick and soon I was saying goodbye to Leo.

As I departed the ship, I was hoping to get a photo of the famous town, something worth sharing, so I went first in search of an enviable vantage. Not far away I found a small park, about a quarter-acre in size. I made my way through its iron gate and then across a green, cut lawn to the waterside, the park was perched above a modest cliff but still the vantage was pretty good. I snapped a few photos then fell into conversation with a fellow that had apparently, my conclusion anyway, slept on the bench he was sitting on.

He was about my age, long hair and beard, very Scottish, including a genuine friendliness. He told me part of his story, including his ongoing search, after leaving a life of constant work as a fisherman, to make more of a short life. Although we had different ideas about where to go and how to get there, and he wasn't on his way to anywhere by the way, he was just going, we agreed on the underlying reason for embarking: a general discomfort with the standard offered to anyone that embeds, start to finish, into society's normal.

Robert was dressed all in green and browns, his luggage was a bag that he carried over his shoulder, he was dirty, teeth and skin, and wet, but none of that mattered. He was free and that's what he celebrated the most. Like so many meetings with strangers, this meeting was brief, but it was also significant, as many of those short visits tend to be. I never did get a satisfying image of Oban; perhaps my supposed search for a vantage was actually a search for a Robert, in hindsight.

Beyond the park, I followed a route that I assembled the day before. I used single-track to navigate around a portion of the main road that headed south out of town and along the way was passed by a road cyclist clad in Lycra. I caught him on the next climb and we stayed together for a handful of miles. Along the way he asked a lot of questions, I did the same, in the process I learned a few more valuable details about where I was headed and where I'd been. Local knowledge should never be undervalued; it's far richer, for example, than any Google search. Far from Oban, jumping ahead in this story, this fellow would continue to check in with me from time-to-time. Sadly, I've not heard, through my website, from Leo; and certainly, the fate of Robert I will never know.

I didn't realize it at the time, because throughout this day like most others I made plans as the day unfolded including where to stay, but I was on my way to a night in Tarbert, a village very similar to Tobermory where brightly colored buildings from a former fishing heyday are lined-up side-by-side along a quaint waterfront. Typically on my bike tours, I try to book a bed, using a variety of sources but especially Airbnb, between 4 and 5:30 pm. When camping, which I rarely did on this tour, I look for a campsite after six. My route from Oban to Tarbert was as scenic, and through similar terrain, as the day before, an enviable ride by any measure. At times, trapped on the primary road, no smaller routes available in this part of the Highlands, I had to negotiate high speed traffic but it was rarely more than an occasional car or truck. Overall, the experience was peaceful, a route I could easily recommend to just about any cyclist.

Based on recommendations from "D" back on the Isle of Lewis, I was able to avoid a large section of primary road, the A816 between Kilninver and Kilmelford. Instead I took "the scenic route", in truth all of Scotland's Highlands are scenic, which turned out to be far rougher than "D" had suggested. Beyond the paved, fast, single track, from Ardmaddy, where the road ended at a pubic gate, to Degnish I negotiated many more gates on, more significantly, some of the roughest tractor track I've encountered on any of my tours, including some very steep climbs where the road degraded even more, to bedrock and loose gravel. It was only about six miles, but I earned every inch on my steel bike, packed for touring.

When I reached the other side I was grateful for the experience but also relieved to be on a surface that was not constantly threatening the integrity of my tires and rims. the last section was a steep descent with large stones scattered here and there, each of them an awaiting tragedy. I did my best to navigate at a pace that nonetheless inspired me to smile. At the bottom, the road turned hard left, or gentle right. I took the left option onto deeply potholed but otherwise much more favorable paved single track. Nearby, a bench awaited no one but me. I stopped for a memory photo and then continued towards Melfort Village, a charming community on the water that was obviously favored by the sailing community, and nearby eventually rolled back onto the A816.

If not for ferry boats, my advance south out onto a long peninsula that contained Tarbert and the much more well known town of Campbeltown, would have been a very long, and unadvised, out-n-back for a guy that was trying to cycle to Istanbul. Pausing for a moment on that thought, arriving to Tarbert for a guy that was on his way to Istanbul was also not advisable! But on this trip, like my other adventures by boot, boat, motorbike, and, bicycle, I was here to celebrate the journey and with that in mind Tarbert and it's far flung peninsula were excellent places to explore.

A few miles before arriving to Tarbert, I nearly rode directly to the location of my next ferry boat, the village of Kennacraig where I planned to travel by ferry boat to Islay, the southernmost island of the Inner Hebrides, the following morning. Instead, i made a u-turn, thinking about that end-of-day grocery shop for dinner this evening and breakfast tomorrow. It turned out this was a good last minute decision for at least two reasons, lodging in Kennacraig was sparse and there was no food to be had, no grocery shops or restaurants. In contrast, the village of Tarbert, despite its modest proportions, not only had many shops but also a rich history, involving a well preserved remnant of a castle, high above the town, and a story that included Robert the Bruce and other famous characters from Scottish history.

On this evening, I came up short using my favored Airbnb smart phone app. There were options but nothing fit comfortably into my daily travel budget and those that came close were sparse. The best, cheapest, Airbnb option was in Kennacraig but I quickly discovered that the inn keeper was sick and so was not taking guests for the evening. In a setting like Tarbert, a bustling little town, a sensible plan b is always "ask the locals." Soon I was chatting with a man one level above the street, just outside of one of the town's primary fish processing plants. He advised me on some affordable options and also directed me to the best fish and chip shop in town, which didn't open for about another hour.

Unfortunately, his tips all turned out to be either booked or not responsive, ring the bell a few times and no one arrives to greet you. I went back to my smart phone for a deeper search, using Google maps and key words, like "guest house." And also talked to another local. All this led to the Tarbert Hotel, which I feared would be well above my budget. However, I was thrilled when the bar keep said it was 40 or 45 pounds. Not cheap, but certainly comfortable given the day was nearing its conclusion and I had a significant number of miles and hills climbs in my legs since departing Wick.