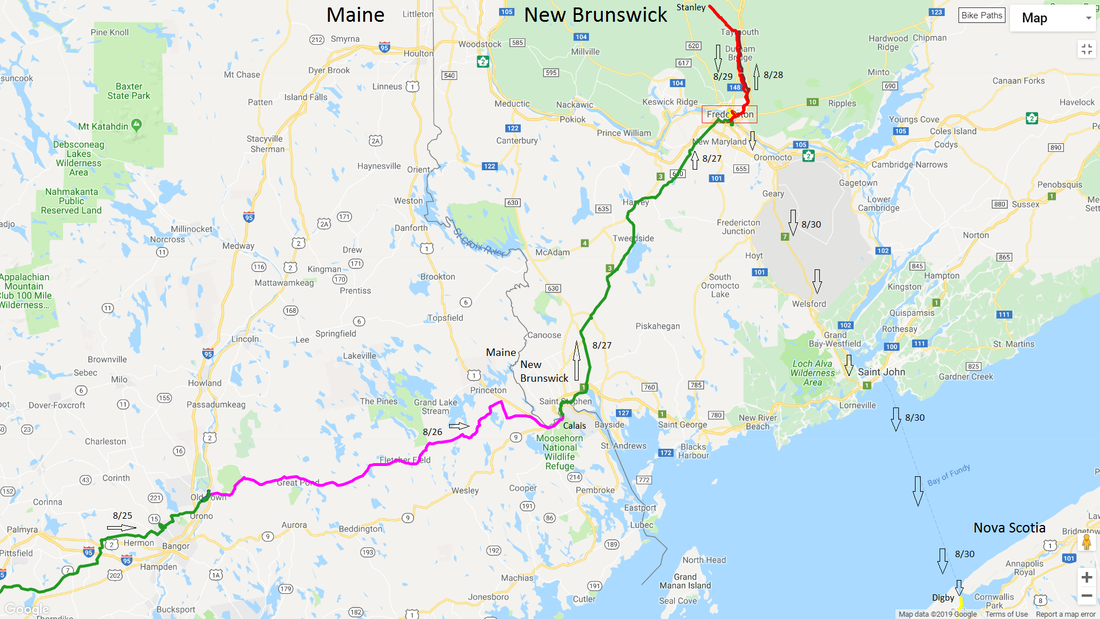

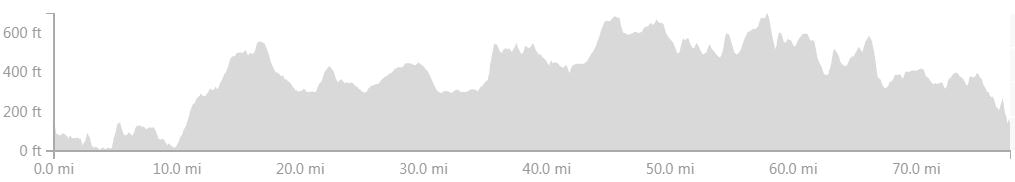

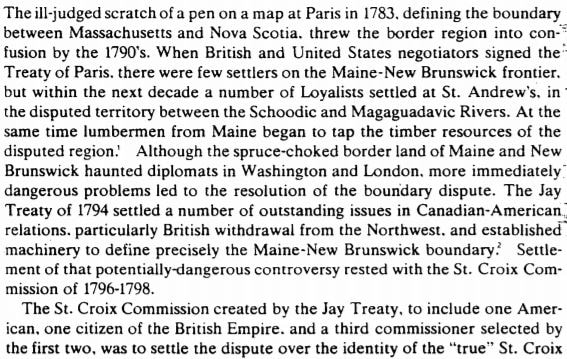

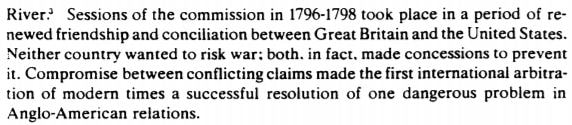

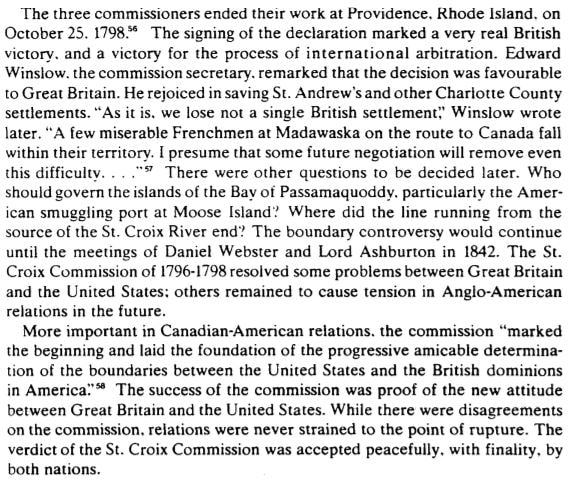

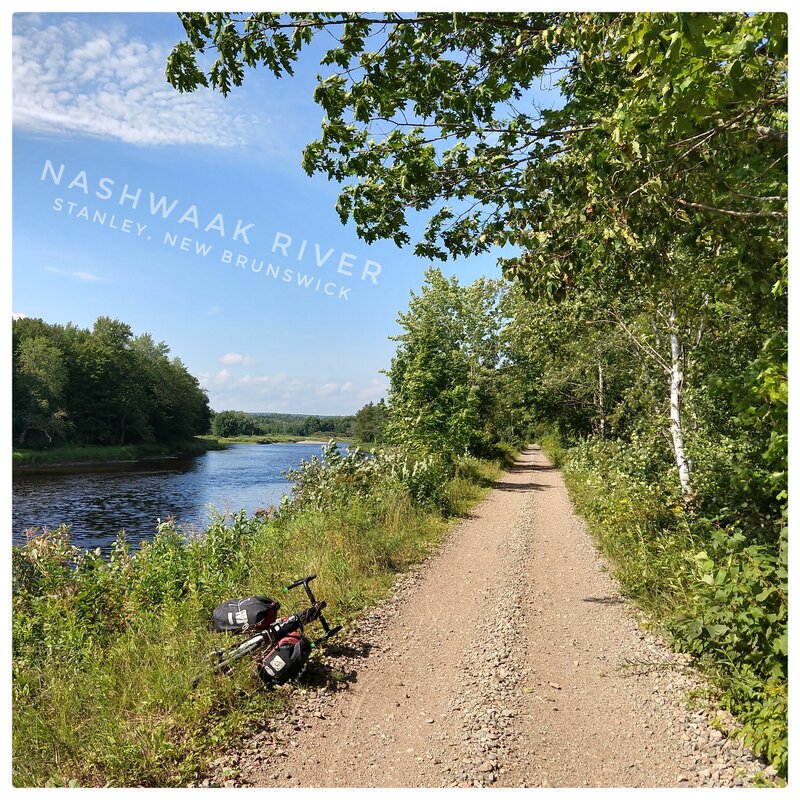

This map includes a portion of my route through Maine including Stud Mill Road (pink). The green line, center, provides a GPS impression of my route from Calais, Maine to Fredericton, New Brunswick; the elevation profile (above) is from this section. I crossed the border into Canada at Saint Stephen. The red line and nearly overlapping brown, records my route to/from Stanley from Fredericton, 27-29 August 2018. My departure route from Fredericton to Digby, by car, ferry and bike, is provided for perspective. Background: This is the fourth blog entry, the first a prologue, in a series that when completed will tell the story of my 2018 autumn cycling tour through New England (United States) and eastern Canada including Newfoundland and Labrador. Please scroll down this page to read the story in the order that the events occurred starting with my arrival to Maine on 10 August 2018 described in the prologue, Going Full Tilt to Newfoundland and Labrador. On a hill high above the St. Croix River, the border between the United States and Canada in this remote corner of Maine and New Brunswick, I stirred from my last phase of light sleep after an evening, no doubt, spent dreaming, in REM, of my adventure on Stud Mill Road the previous day ... I was nestled quite comfortably in one of two available beds (for just 40$ per night) in Ray's AirBnB, less than a mile as the crow flies from Saint Stephen, New Brunswick. The GPS record of my ride, captured using Strava's smartphone app, suggests I departed Ray's home at 7:55 am on 27 August, my habit, roughly 8 am, on bicycle tours to date. I often ride until about six post meridian and the next morning, my reward, enjoy a relaxed coffee before kitting-up for another full day on the saddle. Calais is just half way around the arc of the northern hemisphere from the equator to the north pole, 45.2 degrees north latitude, but I could already feel the familiar chill of an approaching autumn as I descended Ray's driveway at close to 30 mph towards Route 1. A significant feeling given I was eventually hoping to reach Blanc-Sablon, Quebec, at 51.4 degrees, and from there spend most of a day exploring farther north into Labrador. The extra six degrees of latitude between Calais and Blanc-Sablon doesn't sound like much, arithmetically, but the difference is quite massive when the interplay of surface angle (on a roughly spherical Earth) and absorption of sunlight is considered. Without getting into the physics, at 51.5 vs. 45.2 degrees considerably less heat energy from sunlight is retained in the atmosphere and absorbed by the ground, including rocks and vegetation. In Blanc-Sablon and Labrador, I would be, quite literally given my light cycling gear, at the mercy of an environment that is a world apart from Calais in average daily temperature and all of the other weather variables that come along with a cooler atmosphere. I turned right onto Route 1 and within a few minutes was negotiating a round-a-bout. I took the second exit, crossed a wooden bridge over the St. Croix and came to a full stop, as required, at one of Saint Stephen's border-crossing stations, the smaller of the two, this one conveniently reserved for non-commercial traffic. Without a car, motorcycle, another bicycle, or even a pedestrian in sight, at least six agents were, understandably, somewhat mindlessly tapping away at their keyboards inside a small barracks close to the bridge when I sauntered into their milieu. Each of them lifted their gaze and my impression was that they were silently competing for something to do, each one wanting to process the, suspicious, of course, Lycra-clad visitor. Following glances more than words, audible questions followed, the usual ones, to determine if I was a threat to peace and harmony, or not. At this point, my heart rate and internal body temperature steadily rose as I responded to the battering. But eventually, after going to the edge of a tenuous crescendo, the chosen border agent and I found a common ground, shook hands and even laughed a bit as I subsequently shared my ambitions for the tour and he asked some curious, friendly, questions. The delay was only twenty minutes or so, maybe a half-hour. As I rolled away, I looked back to the bridge over the St. Croix River from which I'd come, I wanted to capture a photograph of the quaint border crossing but instead I pressed-on, concerned image-taking might lead to a new interrogation, perhaps involving the US side of the border as well. The St. Croix River, for the most part unheard of by Americans and Canadians, is nonetheless a river worthy of exploration, flowing through what is as close to "wilderness" as the average traveler is likely to experience in their lifetimes. In addition to its near wilderness character, the St. Croix, two centuries ago, played a fascinating and significant role in the history of two countries. The excerpt below captures some of that history, from The Diplomatic Search for the St. Croix River, 1796-1798, an article written, decades later, by R.D. and J.I. Tallman (Acadiensis, pages 59-71), This article goes on to document the historical facts, in some detail, leading to the following conclusion which confirmed the identity of the "true" St. Croix, versus other rivers in the area including the Magaguadavic River, and established its geopolitical significance,  Blackburn Barrier City Pannier Blackburn Barrier City Pannier And so it was written and officially sealed, the St. Croix became the border in this region between two adolescent, in time and character, nations, one of them seemingly destined, in hindsight, to add "in God we trust" to their coins and official motto to, apparently, "relieve [the US citizenry] from the ignominy of heathenism." Ghastly. From its headwater lakes on the Maine-New Brunswick border known as the Chiputneticook Lakes the St. Croix River comes to rest, its sediment burden dropped, its remaining energy dissipated, seventy-one miles downstream at Passamaquoddy Bay, namesake of a Native American tribe that persists to this day on both sides of the border. Just outside of Passamaquoddy Bay is the energetic Bay of Fundy, famous for it's tides, fossils, and scenic red-rock splendor. I'll have more to say about the Bay of Fundy in my next blog entry when, shortly after departing Fredericton, I cross it from St. John, New Brunswick to Digby, Nova Scotia on a ferry boat. From the border station and the "true" St. Croix, I rode east through the community of Saint Stephen and then northeast towards Oak Bay where I glimpsed nearby Passamaquoddy Bay for the last time on this tour. At Oak Bay, my GPS trajectory sent me north, the direction that I maintained with only a slight eastward deviation all the way to Fredericton. Not far from Oak Bay, the road gradually began to climb at a comfortable grade (see elevation profile above) signaling my arrival to the St. Croix Highlands, a little known range belonging to the Appalachian Mountains. To the east, outside of my trajectory on this tour, beyond St. John, New Brunswick, the St. Croix Highlands give-way to the equally anonymous Caledonia Highlands. North of Fredericton, the most expansive of three "highlands" in this part of the Appalachia, the Miramichi Highlands enclose the northern edge of a region known as the New Brunswick Lowlands, a long and wide southwest-northeast valley that bifurcates southern New Brunswick. The St. John River, en route to its terminus at the Bay of Fundy, runs roughly through the epicenter of the New Brunswick Lowlands where it passes by, aptly named for its size, Grand Lake. From Oak Bay, I rode on to Honeydale then Lawrence Station via asphalt surfaced roads that were rough at times, from damage caused by cold and wet winters, but nonetheless comfortable for a cyclist given that they were lightly trafficked other than a brief stint on Route 3. At the intersection of Route 3 and Tweedside Road, in Brockway, New Brunswick, I took a right onto Tweedside and immediately found myself on a quiet, steel and wooden bridge (see image below) a few meters above the enchanting Magaguadavic River. Recall in 'The Diplomatic Search' cited above, the Magaguadavic was considered by some contemporary witnesses to be the "true" St. Croix. In this part of the river's meandering journey from Magaguadavic Lake to Passamaquoddy Bay, the river's pace is nearly imperceptible, reminiscent of a black water slough in the southern United States. The Passamaquoddy translation of Magaguadavic is "river of eels", a reference to the seasonal migration of American eels to and from the river, a species a childhood friend, Charlie Bean, and I often encountered whilst fishing in "swamps" in eastern Massachusetts (scroll down for more details in the prologue of this tour, Going Full Tilt to Newfoundland and Labrador). From the Magaguadavic, I continued north towards Oromocto Lake, a large, (turns-out) shallow lake that is easily discernible on even low resolution maps. Tweedside eventually transitioned from rough asphalt to dirt, aka "gravel road." The surface was sometimes rutted, loose, embedded with large and small stones or some combination, but nevertheless always wide and varying enough, between soft shoulders, to easily avoid these undesirables. My proximity to Oromocto Lake was occasionally made obvious by glimpses of the lake itself, here and there, through breaks in the surrounding deciduous forest. Amidst bird song, mostly sunny skies, light breeze, and a near absence of combustion engines, I was eventually inspired to turn-around, my last chance according to my GPS, and deviate a short distance to the lake shore via a short cul-de-sac, Lane 13, used by a few summer residence to access their cabins. A moment later, after riding down a narrow, two-track, dirt road inside a tunnel of overhanging green, yellow, and orange maple and birch foliage, I popped-out into an enviable scene, much loved cabins, lined-up side-by-side along the lake shore, each one surrounded by a manicured lawn and other familiar, human, comforts. It seems I had arrived during a slow part of the cabin season, all but one unit was idle, without sound or other signs of occupants. The one exception was under renovation, the back deck, by a local carpenter. On this spontaneous stop, I was hoping to refresh my water supply, get closer to the lake for a photo, and enjoy a brief lunch. Part-way down the driveway I hailed the carpenter, he was immediately welcoming and we seamlessly fell into a flowing discussion that wandered from the shallowness of Oromocto Lake to American politics, a favorite among Canadians whenever an American is nearby and who could blame them. Despite proximity, the character and priorities of the average Canadian are much different from their neighbors south of the border where modesty has long ago been abandoned, by the majority it seems, in favor of an attitude that is essentially we are free to take everything from everyone and at any expense. An attitude that has left even the most vociferous, free-society supporters rethinking their sermons, including the author of this convoluted blog entry. With disagreements in mind, between individuals and groups including nations, I want to share an important conclusion from this chance meeting with the carpenter, a meeting that took place along the brilliantly lit and inviting shore of Oromocto Lake: at this enviable juncture, two strangers became friends despite innumerable differences in paths, interpretations, and conclusions. This has been the norm on my journeys, including trips through Europe, Central and South America, Antarctica, and North America, a fact that fills me with hope when I consider the sad state of the world's democracies in the current age. When I consider the destructive implications of human disagreements and the related observation that our species rarely seems to accommodate lessons from the past, I sometimes wonder if the solution - a future free of war, free of racial prejudice, etc - is simple, positive actions of everyday people and their innate desire to open their hearts to friends and strangers. This has become one of my core principles, refined and evolved over many years of exploring by boot, boat, motorcycle, and bicycle, opening my heart to everyone and I have no regrets; only evidence that positive actions lead to positive outcomes, each set inspires more of the same, and the effects are felt, imperceptibly but nonetheless inevitably given (e.g.) Einstein's Space-Time fabric that connects everyone and everything, well beyond the Andromeda Galaxy. Shortly after filling my bottles with well water and capturing a digital image of my RLT leaning against a paper birch above the lake (see image below), I backtracked to Tweedside Road, made a right turn and shortly thereafter transitioned back onto Route 3, a high speed, uncomfortable, experience for a guy on a hollow-tube, Reynolds #853 steel bicycle. But the dread was relatively brief, a few miles beyond Harvey I transitioned, right, onto a relatively quiet road. Route 640 brought me past the community of Yoho and nearby Yoho Lake where my mind inevitably, if you knew me you'd understand, wandered to Yoho National Park in British Columbia (western Canada), the location of the famous Walcott Quarry, the middle-Cambrian Burgess Shale, and the famous Phyllopod fossil layer that eventually created far and wide disagreement among Paleontologists about the history of vertebrate evolution. If you ever visit the park, I strongly advise joining a park service tour of the quarry which requires a (bonus) strenuous hike at altitude to the famous fossil layer. In Hanwell, by now approaching the city limits of Fredericton, all modes of combustion increased dramatically, in number and pace. But I recall a wide shoulder and in general much less anxiety than my brief stints on similar Route 3 earlier in the day. I followed Hanwell Road (Route 640) to a bridge over the Trans-Canada Highway. At this point, following a comfortable day of exploring, across the St. Croix Highlands and the New Brunswick Lowlands, I'd arrived to a place I knew well (scroll down for more details in the prologue of this tour, Going Full Tilt to Newfoundland and Labrador). And perhaps this was partly why the traffic had less of an effect on my mind, familiarity and the knowledge of friends nearby buffered my otherwise high sensitivities to traffic noise and proximity. Visiting friends that lived in the area was the purpose of my excursion this far north into Fredericton. I wasn't sure how many days I would spend visiting, maybe three or four. When I departed, my plan was to backtrack south to St. John, cross the Bay of Fundy by ferry to Nova Scotia, and then resume my trajectory towards Newfoundland and Labrador. Not long after crossing the Trans-Canada Highway overpass, I crossed over Route 8, navigated upper Fredericton, and then began a fast descent towards the south bank of the St. John River. Along the way, about half-way down the descent to the river, I casually rolled through the University of New Brunswick's west gate on Kings College Road. I was heading to Bailey Hall, the building where I spent the majority of my five years as a PhD candidate from 2000-2005 studying the ecology of marine birds and bio-statistics. I took great pleasure riding up, onto the lawn from Bailey Drive, just inches from windows looking into Bailey Hall, where I settled-in for a well ventilated lunch, anonymously, at a familiar picnic table. From this perspective, I enjoyed a devious pleasure: watching the community pass by, all the while pretending to be a stranger among them. Perhaps part of my satisfaction came from memories of a much different character, the person that I was, inevitably given my inexperience, in graduate school. High stress and high speed ruled, so much so that I narrowly avoided, as many graduate students experience, derailment on a few occasions. Near derailments withstanding, thirteen years had passed since my former supervisor, Antony Diamond, aka "Tony", raised his hand to shake mine and stated "congratulations Dr. Breton" moments after I'd successfully defended my thesis. I had learned so much over the intervening years, painfully at times and with regrettable casualties. Casualties never forgotten, I nonetheless, along the way, descended all the way back down to Planet Earth, back to eye-level with its precious biodiversity and the early-life impressions, from that enviable perspective, that inspired the journey. My need for calories and childhood enjoyment of harmless deviance satisfied, I followed-up my lunch with a visit with administrators from the Department of Biology that I will always recall with fondness for their seemingly inexhaustible patience and kindness. Of course, after thirteen years, some of my friends, these administrators that administered with their hearts open to the young people that were full of questions, stress, and even fear on any given day, had retired. However, two among them, still administering their assistance, etc, from where I last saw them in the summer of 2005, recognized me almost instantly despite my gray hair, essentially all of it by now, beard the same color, and Lycra. I embraced both of them, Marni Turnbull and Margaret Blacquier, each hug was worth the bicycle journey from Bremen, Maine. and we spoke as if there had been no intervening years whatsoever. It was good to be back in their company; and their smiles, as I departed, were contagious, with lasting effect, well beyond my next stop on a bridge overlooking the Saint John River, down the hill from the University, in lower Frederic-town. Already my visits with friends, from my past, were going well and three days later, jumping ahead, I'd depart feeling very good about my decision to extend the tour this far north into New Brunswick. Much of lower Fredericton is built, precariously, on the wide, south bank of the Saint John River. A tenuous relationship that often did not go well prior to construction of three dams, beginning with a hydroelectric dam below Grand Falls (1925), and concluding with Mactaquac Dam (1965) twelve miles upstream of Fredericton. Images of partially submerged homes and other assets, in black and white, can easily be found hanging throughout city residences and businesses. Apparently, being underwater was a normal part of being a Fredericton resident for many decades. The Maliseet, the indigenous people of the Saint John River Valley, referred to the river as Wolastoq, meaning "bountiful and good." Centuries later, in 1604, Samuel de Champlain explored the mouth of the river on "the feast day of John the Baptist" and named the river, on his maps, Saint Jean. Saint Jean was subsequently anglicized to Saint John by the predominantly English speaking residents of New Brunswick. A few thousand years after the retreat of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, ca. 10,000 years ago, long enough for vegetation to reclaim the landscape and form thin soils, the ancestors of the Maliseet wandered into the Saint John River Valley, Samuel de Champlain's "discoveries" withstanding, including the banks above the river that would eventually support Fredericton. It is fascinating to imagine, as I sometimes did when peering out my graduate student office window from the second floor of Bailey Hall towards the St. John River and its wide valley, the scene, ca. 3,000 years before the Maliseet's arrival, just after the retreat of the Laurentide Ice Sheet when all of New Brunswick, and Maine too by the way, was stripped bare of soil and vegetation: picture in your mind bedrock, no vegetation or soil in sight, sometimes bare, sometimes overlain with a variety of glacial tills (sands and gravels) and massive glacial erratics here and there, boulders that were carried as much as hundreds of miles from their source by flowing ice. You might also see, in your minds eye, blocks of ice as large as city blocks, partially buried in outwash (more sand and gravel). What you're seeing is the evolution of a kettle hole. During this early stage of glacial retreat, blocks of ice became separated from the main ice sheet and were slowly buried, sometimes completely, other times with their tops still exposed. With time, the ice, buried or not, inevitably melted leaving behind a water-filled depression. Many of these depressions, known as kettle holes, persist to this day. They are the home, in modern times, of a variety of freshwater turtles and fishes, cattails and pickerel weeds, dragonflies and mosquitoes, and much more, each organism a precious component of Planet Earth's biodiversity. For anyone not familiar with the topics of biodiversity and biodiversity conservation, I highly recommend reading E.O. Wilson's now somewhat dated The Diversity of Life for a very readable introduction to biodiversity, a term that refers to the diversity of life, possibly 100 million species, on Planet Earth. Following that introduction, curious readers should also consider E.O. Wilson's latest book, The Social Conquest of the Earth. This recent publication documents, in part, the current species extinction (conservation) crisis, the worst ever recorded since the evolution of species on Planet Earth. As this observation implies, backed-up by the Science of Paleontology, biodiversity is under unprecedented assault by selfish mankind. E.O. Wilson, an emeritus professor at Harvard University, has been at the center of the biodiversity conservation battle for decades. A third, The Song of the Dodo by David Quammen, is also exceptional despite it's now somewhat dated publication date. This book documents, in some detail, mans sad relationship with biodiversity through the ages and how those interactions have altered species distributions, ecosystems, and caused many species to suffer extinction well before their time (a species typically persists for about 1 million years in the fossil record). Despite Fredericton's long tradition of accommodating trade and other communications with the outside world via, naturally, the St. John River, the railroad eventually found its way to Fredericton. With the railroad eventually came a steel truss railway bridge, in 1938, over the river from South Devon to Fredericton (South Devon was subsequently annexed). However, it seems precedence never rests and so with the post-WWII advent of highways and transport by truck, rail transport, like river transport before, began its own decline and the tracks leading to the Fredericton Railway Bridge saw less and less use leading to deregulation of the track including the scenic bridge over the St. John (in 1996). Fortunately, the bridge was never removed, and ownership has since been transferred from the Canadian National Railway Corporation that built it to local and regional governments. Around that time, the bridge was renovated, tracks removed and replaced by a boardwalk, for pedestrian and bicycle use. Eventually the bridge was integrated as part of the Trans-Canada Trail, "a cross-Canada system of greenways, waterways, and roadways that stretches from the Atlantic to the Pacific to the Arctic oceans ... it is the longest recreational, multi-use trail network in the world." As I made my way to Fredericton from Calais, I was looking forward to the simple pleasure of riding a bicycle over the Fredericton Railway Bridge for the first time. I had walked over the bridge many times as a graduate student, but at that time there was no (bi)cycling in sight on either side of my trajectory, towards or away from Fredericton. Standing on the pedals, head tucked close to my handlebars, a grin easily detected on both cheeks, I descended out the University of New Brunswick's north gate, through a well timed green traffic signal, onto University Avenue. From University I took a left onto Charlotte and then, pretty quick, a right onto Lincoln Path, a bike and pedestrian way. A moment later I pedaled over busy Route 102 and then coasted onto the historic Fredericton Railway Bridge. The sun was shining through perfect, puffy white clouds, amidst a reliable breeze that cooled the ambient temperature above the river, within the scope of the bridge and its fortunate occupants, a couple of comfortable degrees during warm summer months. It was Monday afternoon, most people were working and so I had the bridge almost entirely to myself. I paused for reflection and images, I've added one of those photos below. As I watched the river rush past, I was reminded of the behavior of flowing water, that water does not decide where or how fast, etc, to flow, it simply takes the path of least resistance and offers no objection, coming or going. Mesmerized by the river, as humans often are when they watch waves washing up onto a beach, I entered a privileged space, a place of surrender. Perhaps this is part of the attraction of water in motion, it is a natural path to meditation, to a space where we are inspired to simply "be" in the here and now where we surrender to the thoughts and habits that otherwise define our state of mind, happiness, and more. No doubt my old friend and mentor John Quimby would have agreed and encouraged me to listen to the river in my heart. Master Quimby, as Sean Donaghy and I referred to him during days spent competitively tying knots, a fun past-time, on far-flung Seal Island (summer of 1995), used to dictate his daughters poems from memory. One ended with just one word, which I never forgot, that word was "be." I didn't rush to get off the bridge, but eventually a craving of a different kind compelled me to locate Coffee and Friends in downtown Fredericton where I relinquished my pent-up anticipation of the chemical signals, all glorious, that accompany a well made (decaffeinated) latté (see image below). As I sat and sipped, occasionally looking out the window towards the bi-directional city life that was coming and going on King Street, I assembled and confirmed my plans for the next three days. This included, for tomorrow, an out-and-back, overnight journey along, in part, the Nashwaak River and its namesake trail, a recently converted rail-to-trail, to visit my former PhD supervisor, Tony Diamond, and his wife, also a friend, Dorothy, in Stanley, New Brunswick. After departing the coffee shop and checking into my latest AirBnB home-on-the-road in the hamlet of Devon on the north bank of the Saint John, I joined my ex-girlfriend of seven years, now a friend that will always be close to my heart, and her family for a marvelous dinner back on the south bank of the river. Approaching ten post meridian, I was back in my own Lilliputian apartment, hosted by Danielle and her family for 36$, on the second floor of a house built a century before I was born which included a kitchen, bathroom, and bedroom plus a fan to sooth my sleep and protect the integrity of my dreams. By 11 pm, I was listening to the seemingly far away sounds of a few cars as they swooshed past on Main Street. By mid-night, exhausted from a full day of exercise, traveling, and visits, all of my sheep were in their pasture. The next morning, I started my day at a coffee shop putting out small fires, i.e., responding to emails and completing small work commitments associated with my business, Insight Database Design & Consulting. For this purpose, spending a few hours here and there working, tucked away in one of my panniers I was carrying a Dell Inspiron 11 (3000 Series), by the way a marginal laptop that I regret purchasing but it's nonetheless done the job on several bikes tours to date. Erin and I subsequently reconvened mid-day for lunch at Dolan's Pub in downtown Fredericton for a much more personal opportunity to share stories, laugh a bit, and in general enjoy being back in each others company. I'll have more to say about Erin and her family when I write about the last evening of my visit to Fredericton, below. From Dolan's, already kitted-up, I navigated by memory from graduate student days through Fredericton's busy downtown quarter to Lincoln Path, took a left, and rode over the Fredericton Railway Bridge. On the opposite bank of the Saint John, in the village of South Devon, I rolled-onto the Nashwaak Trail. Much of the trail was formerly the rail bed and line that led to the, presently, enchanted foot bridge. The initial couple of miles of the Nashwaak are a mix of public roads and non-rail related bike paths, the latter surfaced with either hard-packed pea gravel or concrete. As I approached the unimposing town of Penniac, about five miles from the foot bridge, I veered left off of River Road and for the next twelve miles pedaled north along the scenic east bank of the Nashwaak River on converted rail-to-trail. The landscape was a mix of grass hay agriculture, associated farm buildings, forests, the river, oxbows and other wetlands filling-in the middle. Along the way, I passed by the sleepy towns of Manzer, Nashwaak, and Durham Bridge. These are towns that all of us should envy, for their solitude and, one would guess from their appearance and location, respect for what's important in life. The handful of people that live in them were indoors when I passed by, or elsewhere. Rather than man and machinery, the soundscape along the Nashwaak was dominated by gentle wind, wrestling the mixed perennials and grasses along the trail-side and branches above my head, the latter negotiating for the best place to operate their numerous photosynthesis factories, billions per branch no doubt. In addition to these bountiful pleasantries and long before I reached Taymouth where I exited the Nashwaak Trail and headed west on English Settlement Road towards Stanley, my body and bike experienced a genuine thrashing from the trail surface for many miles. Although the government agency responsible for building and maintaining this part of the Trans-Canada Trail had removed the steel tracks, coarse gravel typical of railroad beds remains. My tires often dug deep into this surface making it difficult to steer the bike, stay upright, and maintain a comfortable momentum, all of which were quite unexpected for a guy operating a machine known for its inherent stability. But much worse than a little sweat and discomfort, about half-way through the adventure my rear rack began to move so much so that the bike began to sway like a pendulum. I stopped and quickly confirmed my suspicions, the plate that held the forward part of the rack to the bike had completely split, a clean break from hours of barely detectable movement in the rack caused by poorly designed Blackburn panniers and the rough surfaces that I'd ridden over on the Nashwaak Trail and Stud Mill Road a few days before. The issue centered on the lower attachment point integrated into my Blackburn Barrier City Panniers, incredibly a flimsy Velcro strap looped through an even more flimsy fabric loop (see image right) that was, sadly, stitched to fabric on the back-side of each pannier that was itself poorly attached, not quite glued sufficiently, to the hard plastic, pannier backing plate. I noticed all of these bizarre issues right away when my panniers arrived with haste to Maine a few days before I departed for the tour. But as this implies, I didn't have time to return the product, search for and order an alternative. Jumping way ahead briefly, because I want readers to know, when I called Blackburn, after my tour, and told them what happened they refunded my money right away. Kudos to them for providing excellent customer service. Returning to the story, this situation would never have arisen if a bike shop in Massachusetts hadn't of accidentally discarded my much proven and tested Blackburn Barrier Outpost Panniers. Unlike the City variety, which are slightly smaller and lighter (the reasons I decided to try them on short notice), the Outpost model attaches to the lower rack via a hard, secure (no swaying), plastic clip. I had loaned the RLT and racks to my younger brother following my last return trip from Germany. He arranged to have the bike and rack shipped to Maine before I arrived to Bremen. The very light bags were in a bike box that we provided, so light in fact that when a non-thinking employee was cleaning up the shop he heaved my box and bags into the dumpster, neither of which were ever seen again. The crime was not exposed until I arrived to Maine and opened the box that had been shipped from Massachusetts. I was puzzled to find the bike and rack but no bags. Shortly thereafter, following a phone call, the reality of what happened unfolded quickly. And once it was clear, I hastily purchased the City-variety, a decision that I would later regret and on three occasions, the Nashwaak being only the first. More about the other two when I write-up my experience crossing Nova Scotia in the next blog entry. Using some light rope, that I had absconded with when I visited Mr. Goodhue on Vinalhaven (details in part one of this series), and a piece of wood from the forest, I rigged a temporary fix before continuing on to Taymouth where I was relieved to transition back onto asphalt despite the enviable natural beauty and other off-the-beaten-path benefits of the Nashwaak Trail. These challenges aside, for anyone reading this blog entry that might be thinking about riding the Nashwaak Trail, I strongly advise doing so. Just be sure to use a bike with tires that are wide enough to stay on top of the gravel, at least most of the time. A gravel bike with 38 mm knobby tires would likely do the job; and certainly a hard-tailed mountain bike with two inch or wider tires would be comfortable relative to my experience on 28 mm road tires. The name 'English Settlement Road' reveals a lot about the history of New Brunswick, a story shared by Canada and the United States in general. The designation of the border between two nascent countries at the St. Croix River, provided above, is a small part of this story which no doubt is the topic of at least one full encyclopedic series. Without getting into those details (screenplay: reader expels a breath of relief at this juncture), many of which occurred far away from my tour, English Settlement in this case refers to many communities in the area, some of them vanished and others very much still with us including Stanley, New Brunswick. All of these settlements originated in the first half of the 18th century when pioneers were being actively recruited and attracted to the area by the New Brunswick Land Company. Like the land companies of other provinces, Nova Scotia among them, the goal of the New Brunswick Land Company was to "reap substantial profits from land sales." The New Brunswick Land Company ultimately failed to turn a profit, but it nonetheless was responsible "for bringing several hundred settlers to the province and for creating [, e.g.,] the village of Stanley." Despite their awareness that I was on my way from Fredericton, the Diamond's were napping when I arrived, understandably given the delays I experienced on the Nashwaak Trail associated with my broken rack mount. We eventually convened in a shady spot behind their house, where I could remove my stiff, carbon-soled, Specialized S-Works 6 (mountain) cycling shoes, absorb the cool air, and dry some sweat from my adventure on a warm day to Stanley via the Nashwaak Trail and English Settlement Road. Cool ice water added to the effect and soon we were touring the compound including a covey of chickens, of the laying and meat varieties, bountiful vegetable gardens, solar powered sheds, and a fabulous little travel trailer that is apparently much easier on a back than any tent known to man. I had no doubt when I arrived and certainly no reason to raise questions after the garden tour, life is Stanley was as it should be, full of opportunity for productive, unbiased, reflection, the sort that guided Charles Darwin to his theory of evolution by natural selection and Sir Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz to their shared, contemporaneous invention of the Calculus. A locally raised meat chicken that had recently visited the tray of sustenance for the last time took center stage at the dinner table this evening. Equally exciting, on the periphery, was a bounty of non-gmo, organic, nurtured with love vegetables from nearby gardens. After a period of digestion, now after dark, Tony and I took a short drive, north, to downtown Stanley. Even in a moderate rain, I was attracted to this hamlet on a hill high above the Nashwaak. Inside the general store, just about the only store in town, we found a proper bottle of scotch, paid a memorable clerk because of her beautiful smile, and soon made our way back to Tony and Dorothy's home. Part-way through my graduate student experience, Tony and I began meeting on a regular basis, for an hour or two, an opportunity for me, to Tony's credit, to ask questions and otherwise direct the conversation any which way I desired. I often asked about people from our shared science and passion, the ecology of birds. I never grew tired listening to Tony describe the legends that he'd known, and worked with in some cases. Among the latter was David Lack, with whom Tony completed a postdoctoral fellowship on ecology of West Indian birds whilst studying at Oxford University. Second in popularity was typically broad and contentious topics from ecology, such as his thoughts on the debate between Nicholson, a mentor of Lack, and Andrewartha on the mechanisms responsible for the regulation of animal numbers. A third tier, or branch, was the philosophy of science, a topic that seemingly has no end or beginning. Given our history of debating and discussing, an accumulation of many, many hours, you might think that Tony and I would come-up short on the next topic. But that certainly was not the case, over dinner, on our short drive, or after the rocks (ice cubes) were moistened with a bit of Scotch whiskey. Dorothy, as sharp as she was when I knew her in graduate school, weighed-in as well. By the point when it was well past my bedtime, and no doubt there's too, someone finally noticed the time and recalled early commitments the next morning. I enjoyed every moment of this reunion, my only regret is that I couldn't stay longer. However, I think I had proven to myself by this point on the tour if not on previous tours as well, that making a big effort to visit friends as part of any adventure, by bicycle or not, returns much more than any other plans that you might make for the trip. My advice is make time for these visits, no matter how far from your primary objective and path that they might take you. Of course, you can't visit everyone on every tour, so you'll have to make decisions about where to go, who to visit, on this tour or the next. And be sure to go by means other than combustion. By doing so you'll accomplishing much more than you may realize, human beings are visual learners after all. If you ride a bike as I did then you may inspire others to ride a bike as well and with that you'll change their lives, which in turn will lead to more lives changed, all of them for the better. Best of all, I believe, as already noted in a different context but worth repeating, that if you inspire someone then the forthcoming positive outcome will affect everything in the universe in a positive way, including the fate of Planet Earth's too often forgotten biodiversity. Many small, positive effects, can lead to positive global change. That is my wish every time I climb onto one of my bicycles. Breakfast and coffee were as satisfying as dinner. Subsequently, Dorothy and I went to her shed to locate a piece of proper wood and a small piece of buck skin so that I could devise a more reliable, though still temporary, fix for my broken rack mount. Satisfied, I departed the home of the Diamond's by 10 am and mostly glided downhill all the way back to the Nashwaak, about six miles of easy climbing the day before. Rather than return on the Nashwaak Trail, I sensibly followed the asphalt, Route 138 to Canada Street which brought me back to the hamlets of Sandyville and Marysville then ultimately to Main Street in Devon where I had spent an evening two nights before. I was making my way to Key Cycle, on Main Street, where I hoped to find a better solution, a permanent fix, for my broken rack mount. Key Cycle is owned by a local who takes care of the same and is happy to do so. His shop is eclectic for sure and not exceptionally clean, especially the work area (see top image), but that doesn't matter because he's been there long enough to know where to lay down his sandwich without contaminating the bread and is equally able to locate even the smallest screwdriver at the bottom of a random pile of seemingly everything. Exceptions no doubt occur, such as when his assistant moves an Allen wrench from one pile of random parts and tools to another. But in general, progress is made and with few delays at the wee bike shop known as Key Cycle on Main Street in the hamlet of Devon. Quite unexpectedly from Greg's perspective I'm sure, I strolled into the shop at about noon and pretty quick had a new friend, Greg, the owner and chief mechanic, to add to my life list. I explained the situation, what had happened, why, and where I was hoping to get to, Labrador and back, and he didn't hesitate to help. Soon the bike was on a stand and the damaged pieces were being removed. About two hours later, following a fair bit of sparks from a grinder and other drama as his assistant fabricated, using spare parts that were never meant for this job, a permanent fix, my rack and RLT were once again, for the moment anyway, as attached as conjoined twins. It's worth mentioning the bakery next door to the bike shop, I spent about thirty minutes satisfying my desire to eat everything, my norm, in the company of those bakers. I wasn't disappointed and neither were my taste buds. If you need anything bike related head to Key Cycle and arrive hungry, that's my advice. Just be sure to bring some cookies to Greg, he'll let you know where to set them down. If you want to know how satisfying a sense of relief can feel, then I propose that, for starters, you set-out on a long bike tour. Inevitably the bike will break in some way, maybe multiple times, each time this occurs and you manage to get it repaired you'll experience this feeling. That's how I felt as I rode away from Key Cycle, a feeling of rebirth, of renewed everything, as if the excitement of starting the tour was rebooted for my internal synaptic pleasure. From Key Cycle I sauntered to downtown Fredericton and then ascended most of the way back up the south bank of the Saint John, towards Route 8 and the Trans-Canada highway. Part-way I dodged some construction by pulling an illegal, wrong-way dash, through a short tunnel that was closed in the direction that I needed to go. A few turns later, through suburban Fredericton, and I was not only privileged to a beautiful view of the St. John River, it's valley and historic Fredericton below, but I had also arrived to a pool party and my next bed for the night. My AirBnB superhosts, Francis and his husband, greeted me as if I was family visiting after a long hiatus, with smiles and hugs. We fell into easy conversation as Francis fondly looked after my bike, a covered place for her to spend the night, and then provided a quick tour of my room, the house, and the pool. It was a pity, because my hosts and their home (61$/night) were all spectacular, that I had plans that I wouldn't want to miss that evening, dinner with my friends, the Whiddens. However, when I returned later that night I did get a chance to chat with Francis in the tiki hut, beside the pool and amidst an array of playful lights on strings, before I transitioned into a deep, refreshing, sleep. The Whiddens, like all of us, fall short of perfection, but their strengths are nonetheless exceptional. The strength, their passion, that I am most moved by, emotionally, is the value they associate with family; to their credit, a value that they also extend to strangers that come and go over short or long time spans. I was fortunate to be one of the later, in fact I enjoyed seven years coming and going from the "Whidden Hive" on Emmerson Street in Fredericton; the fortunate recipient, at that time, of their second daughters affection. Our relationship evolved, as all relationships do, in our case towards friendship, with a small but quite significant bump, based on emotional expressions of sadness, towards the end that stressed both sides equally. But that low point is now well behind Erin and I, and her generous, forgiving, family; and I'm flattered to the moon to be welcome and embraced as, well, family, as I was before Erin and I split. For my last evening in Frederic-town, I was very fortunate to be invited to dinner and also to catch the entire, much extended over the last few years, Whidden family including children and grandchildren. Somehow we all managed to navigate to dinner plates, fill them with Liz Whidden's fabulous cooking, and then savor each bite between words filled with a clear affection for each others company. Everyone takes part in the clean-up at the Whidden hive, perhaps not every night but spread-out over the week and visits in a way that is natural and another small part of the inspiration this special family provides on a daily basis. Beyond the surface of the dinner table, somewhere close to my heart, two dinners with the Whiddens in three days went far to soothing my soul, towards dispersing the remainder of the emotional conclusion that I mentioned. Thanks to this effect, I departed this wonderful little part of the universe, on Emmerson Street in Fredericton, smiling and looking forward to my next visit, and my next, hopefully enough to be an active part of their inner circle of exceptional misfits. In my next blog entry, I'll open with my departure, the next morning for a ferry boat that would transfer me, a two hour crossing, from St. John, New Brunswick to Digby, Nova Scotia on the opposite shore of the Bay of Fundy. From their, I'll recall my experiences, including a dog attack and a trip to two welders to have my broken RLT repaired, across Nova Scotia to Cape Breton where I boarded an even bigger, overnight ferry, in North Sydney, that would take me to Argentia, Newfoundland, across the wide-mouth of the Saint Lawrence River, the Cabot Strait. Comments are closed.

|

�

André BretonAdventure Guide, Mentor, Lifestyle Coach, Consultant, Endurance Athlete Categories

All

Archives

March 2021

|

Quick Links |

© COPYRIGHT 2021. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed