|

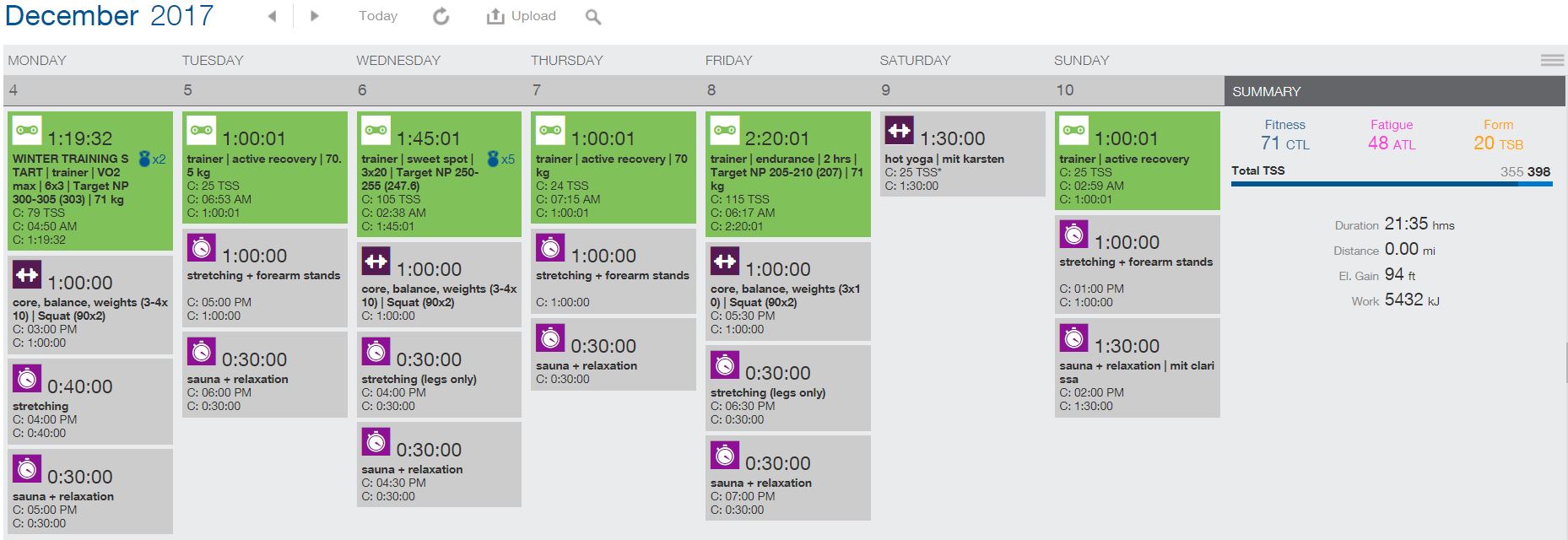

Summary: Inspired by advice from a friend and pro racer, David Krimstock, and the book Training and Racing with a Power Meter, I set-out in early December 2017 to elevate my Functional Threshold Power (FTP) from where I was at the conclusion of racing in 2017, 270-280 watts, to 300 watts. I trained three components of my cardiovascular and physiological systems, endurance, sweet spot, and VO2 max, alongside an aggressive gym program involving weights, core, balance, and flexibility exercises. After nine weeks of structured, multifaceted, and intensive training I achieved or came very close to my ambitious goal, an FTP in the range of 295-300 watts. Since leaving Deutschland and entering the amatuer racing circuit in Colorado, I've had three top-of-the-podium finishes in my very competitive 40-49 age category, a first place finish overall at the Salida 720 racing as part of a pro-expert duo team, a solo fifth overall at the Bailey Hundo, and most recently a solo 7th place overall at the Breck 100. These performances were the result of planning and hard work over the winter and the kindness of others that were willing to share their experiences and knowledge of the sport of cycling. Part 1: Background, Schedule, and Dose.  October 26, the end of the last ride to reach 10,000 bicycling miles in 2018., Hamburg, Germany. Jersey from Subculture Cyclery in Salida, Colorado. October 26, the end of the last ride to reach 10,000 bicycling miles in 2018., Hamburg, Germany. Jersey from Subculture Cyclery in Salida, Colorado. Despite common sense, intuition, and logic, hard work does not guarantee improvement in sport especially as an athlete accumulates years of experience. As that experience approaches about 7-10 years, a hard working / training / recovering athlete transitions to marginal gains for the same effort that delivered much larger gains in the past. Sadly, these marginal gains may not even keep pace with losses, due to aging, illness, poor nutrition, etc, during the same period. Six years into my cycling and racing history (2013-present), at 47 y.o., aging is a significant factor nipping away, each year, at my physiological capacities. Aware of this process and how it might affect my long-term competitive goals, in December I initiated my most ambitious interval training program to date in December 2017 in prep for racing in 2018. My decision to plan and execute an ambitious winter training program in-prep for the 2018 race season began with serendipity when I shared a meal with Shimano-Pivot Cycles sponsored, professional mountain bike racer, David Krimstock, following the 2017 edition of the Fat Tire 40, part of Crested Butte Bike Week. Although I'd considered many times before, especially since I started self-coaching in 2017, integrating a more robust interval training program into my usual endurance training so far I'd failed to make that happen. For some reason, my encounter with David, a super-fast, super-friendly, and studied athlete, finally pushed-me over-the-top of whatever obstruction was holding me back from implementing a full-on, pain cave, interval program. After the Fat Tire 40, I rode-on, eventually finished my 2017 racing season with a 1st place, age 40-49 finish at the Breck 100 on 29 July and then flew to Europe where I pedaled from Hamburg to Scotland on my Niner Bikes RLT 9 Steel. From Scotland, I flew back to the United States to accommodate a month-long cycling tour of New England and adjacent states (USA) to visit friends and family. By the middle of October I was back in Europe and settled-into my winter home (at that time) in Hamburg, Germany for some much needed rest and recovery. I spent the remainder of October casually pursuing, on the nice days, my 10,000 mile year goal which I completed on October 26th. Otherwise, I spent October and November refining ideas about how I might use the winter to interval train, improve my daily nutrition, and add strength to my cycling muscles through weight lifting. By the middle of November, static, Darwinian, armchair, reflection transitioned to physical testing on the bike and in the gym where I further refined my ideas and also measured my base fitness level including Functional Threshold Power (FTP). By the end of November my confidence was high, I knew when, how much (schedule and intensity), how long, and what I hoped to gain. My structured, multifaceted, and intensive winter training program would begin on 4 December 2017, almost a month earlier than any other season to date. By the end of March 2018, I was hoping to push my FTP to 300 watts, my primary objective, through a combination of interval training on the bike, weight lifting (squats, deadlifts, and overhead presses), core, balance and flexibility training, and improvements in daily nutrition including weight loss. As December approached, I performed one 20-minute FTP test in late November, the result was 248 watts. I performed the test on the road, invariably on varying terrain, on a day I felt I wasn't rested and following a few weeks of otherwise light activity on the bike. My guess was then and remains that with fresh legs rolling on an ideal surface, no dips in the road, stop signs, etc, I could have output closer to 260 watts which is the number I used as my FTP, rather than 248, when I started training on 4 December. Before I get into the details of what transpired on and off the bike, it might be helpful to just cover the daily schedule, repeated each week, of my training program. Below, as an example, I've inserted my first week of training for the 2018 season, 4-10 December 2017, from my Training Peaks calendar. Assuming I felt rested enough on Friday to perform 2 x 60 minute endurance intervals, then my schedule would be M-W-F, all other days would be allocated to active recovery or days off. If I wasn't rested on Friday then I rested and instead trained hard on Saturday. On Mondays, typically mid-morning after putting-out any fires as far as clients / work, I'd climb onto the trainer in my office between 9 and 11 am. I warmed-up for 15 minutes then rode for 5 minutes at my functional threshold power, 260 watts, before initiating 6 x 3 minute VO2 max intervals at 105% to 120% of my FTP. If you know your FTP, then your VO2 max adaptation window is approximately 1.05 x FTP to 1.20 x FTP. For me, on 4 December, that window was 299-312 watts. By training in this adaptation window I was training and hopefully increasing the power associated with the VO2 max component of my physiological spectrum. For more details about human physiological systems and adaptation, I highly recommend Training and Racing with a Power Meter from Hunter Allen and Andrew Coggan. Outside of suggestions from David Krimstock, this book was my primary resource for planning the cycling-component of my winter training blocks. At the conclusion of the intervals, I'd climb off the bike, eat a recovery snack, towel off, change clothes, and head to the gym. The first 60-90 minutes were allocated to weight lifting, followed by core and balance exercises, then flexibility. I often concluded each trip to the gym with a 15-minute session in the sauna, or a double-dose separated by 5-10 minutes waist deep in cold water, followed by a short period of relaxation before showering and heading straight for food! It wasn't unusual for me to cash food in my locker which I visited as needed throughout the gym session. Weight lifting consisted of the squat, deadlift, and overhead press. Core and balance comprised six exercises (not always the same) done twice each, 15-50 reps. For example, I performed two push-up sets of 10-25 reps each while balanced on two yoga balls, palms-down hands on one, toes on the other. Sometimes I was tired and managed only 2 sets x 10 reps. Sometime I was more rested and crushed 2 sets x 25 reps. Flexibility involved my cycling muscles, mostly, but not exclusively. Stretching the hams, quads, glutes, and hip flexors were a priority to avoid low-back pain while walking or standing, possibly due to adaptive shortening. Although the sauna and relaxation are simple in concept I believe they are powerful in practice. Of course, there is no need to describe how to sit in the sauna and chill afterwards, but don't let the absence of details disway you. I believe heat and relaxation were important components of my winter training. Wednesday and Friday (or Saturday) were the same as Monday except for the cycling part. Wednesdays were allocated to sweet spot intervals, intervals performed at 85-95% of my FTP. The 'sweet spot' is the the part of the physiological spectrum that marathon-style mountain bike racers settle-into after their fast start and before they pick-up the pace for the last push to the finish. The sweet spot includes the well known / often discussed physiological zones known as tempo and about half of the sub-threshold zone between tempo and FTP. If you know your FTP, then your sweet spot is 0.85 x FTP to 0.95 x FTP. At the beginning of December, 2017, my sweet spot range was 221-247 watts based on an FTP of 260. My training plan allocated VO2 max to my most rested day, Monday, the day following an easy weekend. Next in difficulty and slightly less rested, I integrated sweet spot intervals on Wednesday. Lastly, on Friday or Saturday, exclusively in a fatigued state by this time, sometimes wasted, I did my best to perform two sets of 60 minute endurance intervals. The endurance zone is roughly 69-75% of FTP. At the beginning of December, I estimated my endurance zone as 180-195 watts. However, based on a lot of endurance days on the bike, and testing in November, I decided to increase this range to 200-210 watts to start. On my first endurance interval session on 8 December my goal was to maintain 205-210 watts and I was successful, some evidence, certainly not conclusive, that my intuition was correct. On Tuesdays and Thursdays I worked as many hours as possible before an easy active recovery ride on the trainer and then a shortened flexibility session followed by sauna / relaxation. I varied my active recovery rides, sometimes I maintained a cadence of 90-95 for 1-1.5 hrs. Sometimes I started and finished with 10 minutes at 90-95 rpm with 40 minutes of 105-110 rpm between. Although I don't go into the value of cadence anywhere in this blog entry, it's definitely a topic any cyclist will want to read about. I believe that training cadence is one of the primary ingredients in the recipe of any successful cyclist. The minority of successful grinders withstanding, including former pro-roadie Jan Ullrich. Saturday and Sunday, ideally, I completed an active recovery ride followed by flexibility and relaxation in the gym. Given my busy M-W-F schedule, I sometimes had to work as well, which I tried to do in the mornings. In early December, I was still planning two trips to Spain to add climbing / elevation adaptation blocks to my winter training program. I traveled to Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, from 16 Jan to 1 Feb; and later, to Mallorca from 20 Feb to 12 March. When in Spain my priority was climb, climb, climb, no gym, occasionally stretching, always eating. I took days off to work and recover. I did perform some interval sessions, including VO2 max, and FTP testing in Mallorca but those were exceptions. The rule was 'get on your bike and climb until you hate yourself'. That might sound awful but both trips provided many memorable adventures, each full of surprises with many reasons to smile and reflect. Before I flew to Gran Canaria, I completed seven VO2 max interval sessions. Because I flew on a Tuesday I completed one less sweet spot and endurance session before the first winter climbing block. Between Gran Canaria and Mallorca, back in Germany, I completed two more weeks of training on the bike and in the gym. After Mallorca, sadly by this point experiencing relationship stress that would conclude my German experiment, I added two final weeks of intensive interval training / gym sessions before flying back to Colorado on 28 March. All told, twelve VO2 max training sessions and eleven sweet spot and endurance interval sets. Weight lifting sessions were three-times per week when I was in Hamburg, so about 30 sessions involving a barbell, same number applies to core and balance. When I returned to Colorado I replaced gym and core work with many forms of hot yoga (Midline Yoga) and indoor soccer (Arena Sports) as I increased my cycling hours and waited for my body to adapt to elevation in prep for racing. All cycling was performed on my 2015 Giant TCR Advanced road bike attached to my Omnium Trainer from Feedback Sports, an exceptional, travel-friendly, unit. Thanks to a friend, I have a Quarq power meter attached to my road bike. Weight-lifting, core, and flexibility exercises were completed in the Kaifu Lodge, a short walk from my office and winter home (at that time) in Hamburg, Germany. What I just wrote covers schedule, structure, and logistics, now I'll describe the dose that I chose for cycling and weights and my overall goal / objective for my winter training program. On the bike my plan was to increase intensity by five watts each session (dose) relative to the one before. So if my VO2 max goal was 300-305 during a given week then the goal a week later, assuming I was successful, for VO2 max would be 305-310. I applied a similar strategy to my weight lifting schedule / plan, add five pounds each day (dose) to all of my sets and reps. So if I performed 3 sets of squats by 5 reps at 220 lbs on Monday, and was successful, then on Wednesday I repeated 3 sets by 5 reps (3 x 5) with 225 lbs. My hope was that by increasing power and weight incrementally over many weeks I could gradually and successfully increase my FTP to 300 watts, this was my overall goal. My decision to simultaneously (same week) train three components of my physiological system was motivated by two conclusions: 1) I'd spend less time on the trainer versus training long endurance hours for weeks, then sweet spot, then VO2 max; and 2) adaptation within each system (more power) might, sensibly I thought, cause a shift overall in my power through simultaneous adaptation. I would, I hoped, pull myself up into a stronger, faster, higher performing self by executing a winter training program that simultaneously integrated four structured training components, each imposing adaptations on different part of my body, three motivated by the bike and one by a barbell. To these physical challenges I added plenty of healthy food, active recovery, heat adaptation in the sauna, and relaxation to help motivate adaptation on the off days. This final component, a multifaceted recovery strategy, was motivated by the following reality: adaptation occurs during recovery not training. Part 2: Details Training on the Bike Day one, 4 December 2017, 6 sets x 3 minute VO2 max intervals (3-minute recovery between), followed by weights and core exercise in the gym, then stretching, then thirty minutes for sauna and relaxation. My average normalized power (NP) goal for this first set of VO2 max intervals was 300 watts, slightly above the middle of the target range suggested by David and the book by Allen and Coggan: 260 x 1.05 to 260 x 1.20 = 273-312 watts. Apparently I was showing myself no mercy on day one of my winter training program and I wasn't disappointed, I was able to maintain, despite the high-level of mental and physical suffering I experienced during all of my VO2 max intervals, an average of 303 watts (avg NP) over the six intervals: 296; 303; 306; 307; 304; 303. I went a little under my goal on the first interval, the next five were a smidge above 300 watts. Here's what I wrote in the comments section of this workout shortly after climbing off the trainer: "I'm very close to being able to sustain 310-315 for these 6x3 min intervals, closer to 300-305 at the moment but that's a big leap relative to power when I climbed onto the omnium [trainer] about two weeks ago. My body is adapting quickly, road and trainer power are equalizing though not yet equal. I'm very satisfied with today's result and looking forward to the next 6x3 session so that I can assess how much closer I am to road power." Regarding "equalizing", recall I was testing ideas in November. During this time I was also spending time on the trainer so that my road and trainer FTP would be more, rather than less, aligned, simplifying the arithmetic especially when I flew to the Canary Islands in a few weeks, then later Mallorca, where I would train almost exclusively outdoors and at intensities dictated by my functional threshold power. It's not unusual for a riders trainer FTP to be 10-30 watts lower than their road FTP but the difference tends to get smaller, or even go away, following many hours of adaptation on the trainer. Here's the complete set of average normalized power numbers for each interval from the month of December, Weeks 1-4: December 4-25, 2018 (1) 296; 303; 306; 307; 304; 303; avg 303. (2) 317; 319; 315; 310; 308; 300; avg 311.5. (3) 316; 320; 321; 320; 315; 315; avg 317.8. (4) 326; 328; 326; 327; 323; 320; avg 325. Recall that each week I increased my average NP wattage goal by 5 watts. Week one my goal was 300-305. I actually added 10 watts, not 5, to this range the second week to arrive at 310-315 based on what I felt I could do and the less-than-ideal conditions of my last FTP test. Weeks three and four I increased my wattage goals to 315-320 and 320-325, respectively. A fine detail but one worth stating here, for my trainer profile on my Garmin 520 I integrated lap normalized power as a prominent part of the display. I used this as a "carrot" as suggested by Allen and Coggan, to push myself to maintain, reach for, the planned / targeted wattage range on each interval. I can't understate the value of using this "carrot" trick to reach your goals on the trainer, especially those that involve a lot of physical and mental stress. The same trick is useful on the road and trail. Each week in December I successfully achieved my VO2 max goals, increasing by five watts per week. After a New Year celebration and before I flew to the Canary Islands for my first winter block of climbing I performed three more VO2 max interval sessions in January, Weeks 5-7: January 1-15, 2018 (5) 332; 331; 333; 330; 327; 325; 329.7 avg. (6) 337; 337; 337; 336; 335; 330; avg 335.3. (7) 340; 341; 337; DNF. As you can see, the VO2 max trainer session during week seven concluded with my first DNF, I was unable to finish interval four within the estimated adaptation range, 105-120%. After the session I wrote, "Wasn't rested, should have listened to my inner voice and not started." Maybe I wasn't rested, recall everything else, physical, I was performing each week including difficult sweet spot intervals (85-95% of FTP) each Wednesday. Of course, it's always important to listen to your inner voice, that's the 80-90% of your brain that sends brief messages to your conscious 10-20% but otherwise silently works on crunching numbers, reflecting, and much more. However, what I failed to realize on 15 January, when I blew-up during interval four, was that I hadn't failed. Instead, I'd ridden myself, incrementally, week after week, into a direct collision with my trained-state FTP, likely something very close to where I was before I stopped training in 2017. Looking back to week six, I was successful, I finished all of my intervals in the prescribed zone. If I take the average of the six intervals from that week, 335, then a rough estimate of my FTP during that session is 1.2/335 = 279 watts. Based on my 2017 power data (all files), my FTP was likely about 270-280 watts at the end of racing in 2017. The FTP estimate from session six, 279, is in that range. It seems logical that during week six I'd trained myself back to my trained-state FTP at the conclusion of 2017 racing. Any cyclist that is interested in FTP and other thresholds has not doubt complained that FTP "is just a number", or something similar, a useful reference but not "real" in the strict sense of a threshold. Before this winter I would have quickly agreed, but now I totally disagree. There is definitely something very real about the physiological threshold known as FTP. Whether yours or mine is 290 or 291 or 289 certainly isn't important. But the "line" is a real boundary, that moves around depending on our level of fitness and fatigue. Weeks later when I realized what truly happened during week seven of my VO2 max interval training it was a moment of clarity that I doubt I'll ever forget. The realization, the moment I figured it out, will always be special and it's definitely added significantly to my experience as an athlete. By incrementing by five watts per week I incrementally approached a critical component of the human physiological system and all of the processes and chemistry that this system is composed of, our Functional Threshold Power. From January 16th to February 3rd, I moved my base-camp to Gran Canaria, the largest of the Canary Islands. This was a nice break from chilly, grey, wet Hamburg. When I returned to Hamburg, I resumed my interval and gym sessions for two more weeks, Weeks 8-9: February 5-12, 2018 (8) 345; 345; 346; 342; 334; DNF. (Goal 345) (9) 345; 345; 345; 341; 328; 319; avg 337. (Goal 345) By week seven, in January, my goal was 340-345 watts per interval. Recall that I did not finish (DNFed) the fourth interval of that training session because I couldn't maintain wattage in the adaptation window for training the VO2 max part of my physiological spectrum. Subsequently, the next day in fact, I flew to Gran Canaria where I climbed a total of 58,963 feet over 459 miles on the road bike. I was sick, unable to ride, on three days, airport gunk. I took a few additional days off to rest. Total days on the bike were eight. Surviving so much climbing in such a short time gave me confidence, once back in Hamburg, to up my VO2 max wattage goal for week eight to 345-350 despite the DNF at 340-345 a few weeks before. As you can see from the numbers (above), I had some success, holding 345 watts on the first three intervals, both weeks, and completing the set of six during week nine. I was getting stronger, the ninth week compared to weeks 1-8 were proof of that accomplishment. For what remained of my structured interval training, a few sessions in Mallorca and about two weeks in March before returning to Colorado, I was never able to repeat the numbers, on the trainer, that I put out during session nine. Part of the reason was so much travel during which time my body became less adapted to the trainer. Another part was relationship stress. Nonetheless, as you'll see at the conclusion of this blog and in the next paragraph, all of the VO2 max work that I'd done up to / including my success during week nine was making me stronger. By early March I was riding outdoors under Mallorca sunshine with no excuses to postpone my first FTP test of 2018. I performed a 60 minute individual time trial on a climb that was a few minutes shy of ideal, a big dip downhill before climbing again with smaller dips before and after. Despite the terrain, I averaged 289 watts NP. At minute forty, I was holding 301 watts, right before the biggest downhill section. I don't know because I didn't do any serious testing last summer but I suspect 289 was a personal record. On March 6th, just two days after the first test, I repeated the test on the same section of road, same dips, etc, but this time held an average 292 watts even carrying the fatigue of the test from two days before. Back in Hamburg, on 27 March, I performed one more test, a 20-minute time trial. After subtracting 5%, that test suggested my FTP was 294 watts. Not bad, especially given that I had to negotiate one stop sign during the test. This test suggests that when I departed Northern Germany for Colorado I was confidently, given stop signs, etc, capable of 295 watts for 60 minutes, and perhaps even 300 under ideal conditions. Although issues of adaptation had kept me from pushing higher VO2 max wattages on the trainer I'd nonetheless achieved, or nearly so, my FTP goal at least at elevations I encountered in Hamburg and Mallorca through intensive interval training over roughly four months (Dec-Mar). Success and failure as just described for my VO2 max sessions over nine weeks was essentially replicated, for the same reasons described above, during my sweet spot, 3x20 minute intervals at 85-95% of FTP performed on Wednesdays. Here's the numbers from the first six weeks of my sweet spot training, Weeks 1-6: Dec 6 2017 to Jan 10 2018 (1) 252; 246; 245; avg 247.7. (2) 258; 252; 250; avg 253.4. (3) 261; 252; DNF; avg 255.5. (4) 260; 259; 256; avg 258.3. (5) 264; 264; 261; avg 263. (6) 270; 269; 267 (15 min); avg 268.6. Week one, 6 December 2018, I set my first goal at 250-255 watts. Recall I increased this by five watts each week, thus my goal for week two was 255-260 watts. By week six, I was hoping to stay within 270-275 watts for each 20-minute interval. Notice on week six I faltered (blew-up) 15 minutes into interval three. As I had with VO2 max intervals, I was running into my very real FTP six weeks into my sweet spot interval training. Here's the two weeks between the Canary Islands and Mallorca (back in Hamburg), Weeks 7-9: February 7-14, 2018 (7) 270; 269; 270; avg 270. (8) 275; 270 (17 min; DNF); DNS. My success during week seven was perhaps my very best on the trainer for the sweet spot up to that time. That day I had reverted to the week six goal, 270-275 watts, giving myself a slight advantage to succeed given I'd been off the trainer for weeks riding outdoors on Gran Canaria. The next week I reached for 275-280 watts and blew-up after 17 minutes during the second interval. I never started the third. It's very likely that I was above 120% of my FTP at 275 watts at least on the trainer at that time. My experience performing the much less intensive, relative to VO2 max and sweet spot intervals, 2x60 minute endurance intervals also hit a wall, I began to blow up, during week eight. Here's the first eight weeks, all on the trainer, before my endurance interval training was set-aside during my trip Mallorca, Weeks 1-7: Dec 8 2017 to 12 Jan 2018 (1) 207; 208; avg 207.5. (2) 219; 221; avg 220. (3) 226; 226; avg 226. (4) 231; 232; avg 231.5. (5) 235; 237; avg 236. (6) 241; 240 (40 min); avg 240.5. [Off the Trainer: 16 Jan to 1 Feb, Gran Canaria] (7) 240; 240; avg 240. (8) DNF; DNS. My goal during week one, 8 December 2017, was 200-205 watts for each 60 minute endurance interval. By week six (no trips to Spain just yet) my goal was up to 240-245 watts and I was able to meet that goal, 240.5 watts average over the two intervals. When I returned to Hamburg from Gran Canaria I again, as with my post-Gran Canaria goals for VO2 max and sweet spot, gave myself a slight break by maintaining the goal from week six and was successful, 240 watt average over the two intervals. In contrast to week seven, week eight was a near complete loss. And this was in part because by this time I was single but still living with my former girlfriend in Germany. Relationship stress was very high. Another factor was loss of trainer adaptation. After Mallorca, I never regained the trainer fitness I had during week seven. Part 3: Details Weight Training in the Gym For the readers convenience, I'll start this section by repeating some of what I wrote in the introduction including the basic structure of the weight lifting component of my gym exercises, the squat, deadlift, and overhead press. These were entirely new to my athletic sphere when I started planning in November 2017. I've been performing core, balance, and flexibility exercises since April 2011 and many of these exercises as prescribed by my physical therapist, Dr. John Kummrow (Integrative Physiotherapy), instructors teaching at Midline Yoga (previously at Elan Yoga & Fitness), and massage therapists including Katie Hines. As part of my 2017-2018 winter training, I continued to do these though in different reps and sets to accommodate my goals involving weight lifting. For the remainder of this section I'll write almost exclusively about weight lifting. For questions about any part of this blog entry, including core, balance, and flexibility training, I'd be thrilled to hear from you via a comment or email. The simplest way to replicate my weight lifting schedule and dose for the squat, deadlift and overhead press is to buy the book Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training by Mark Rippetoe. In it he advises a five pound weight increase for beginners per session, 2-3 sessions a week, in the gym. I played-around with weights, reps, and sets, and worked on form, throughout November in prep for December. Mark Rippetoe is also featured in many videos that are available on YouTube, such as this one. They're all excellent, informative and entertaining. Throughout, planning and implementation, I was also coached by my older brother, an accomplished weight lifter and stone mason extraordinaire. I sent him videos and he coached me on form as best he could from a distance. He answered dozens of questions. He was also my inspiration and source of courage to get under the barbell for the first time since I was a teenager. What I discovered, once I went under and over the bar, was I really enjoyed these exercises. Especially the squat. On Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, overlapping with the trainer component of my winter training program, I went to the gym and performed first weights, then core and balance, then flexibility exercises. After these workouts, which I always performed after cycling, I often collapsed in the sauna to relax and wind down. It wasn't unusual for me to spend four hours in the gym. On days I had to be quick I could shorten to 2.5-3 hours by cutting-out some of the peripheral activities and being all business. I focused on work in the early mornings and on rest days: Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday-Sunday. I was late getting Rip's book shipped to Germany so didn't actually integrate his structure, sets and reps, until 20 December. On that day my heavy set for squat was 65 kilograms plus the 20 kg barbell, 187 pounds. I performed many warm-up sets, as prescribed (exactly) by Rip, then performed 3 sets of 5 reps at 187 pounds. Based on Rip's suggestions, two days later I added five pounds to my heavy sets, 192 pounds. The hardest barbell exercise I performed was by far the overhead press, I started at a modest 77 lbs, my heavy sets were 3 x 5 reps just like the squat. I enjoyed the deadlift almost as much as the squat. On 20 December I started my deadlifts with a heavy set of 5 reps at 176 lbs, weights + bar. My heavy set for deadlifts, as prescribed by Rip for beginners, was 1 set of 5 reps. Rip predicted that my deadlift heavy weight would eventually overtake my squat heavy weight. He was right, and that occured on the 5th of February, 2018, when I successfully squatted 220 lbs (3 sets x 5 reps each) and then subsequently deadlifted 232 lbs (1 set x 5 reps). I lost and gained on all of these barbell exercises as I traveled between Germany and Spain (no gym, only cycling). On my last trip to the Kaifu Lodge, where I performed all of my gym training, I was up to the following weights on my heavy sets: squat 221 lbs, press 94 lbs, deadlift 254 lbs. I ran into marginal gains, no longer five pounds per session, about eight weeks in with both the squat and press. I continued to gain with few exceptions with the deadlift. My first three month excursion into the weight room in about 30 yrs delivered significant strength gains. For example, my deadlift increased from 176 pounds, a set of 5 reps, to 254 pounds, a difference of 78 very real pounds. I'm already looking forward to getting back into the gym in about December 2018, based in part on how much I enjoyed my time under and over the barbell last winter but also because I know that the weight training contributed significantly to my accomplishments (so far) racing a mountain bike in 2018. Part 4: Conclusion Armed with great advice from a friend and pro racer, David Krimstock, and the book Training and Racing with a Power Meter, I set-out in early December 2017 to elevate my FTP from where I was at the conclusion of racing in 2017, 270-280 watts, to 300 watts. I simultaneously trained three components of my cardiovascular and physiological systems, endurance, sweet spot, and VO2 max, alongside an aggressive gym program involving weights, core, balance, and flexibility exercises. After nine weeks of intensive interval training interspersed with two climbing blocks in Spain and the work in the gym, I achieved or came very close to my ambitious goal, at least at sea level, an FTP in the range of 295-300 watts. Given my limited experience with the sport of cycling, I suspect that what I did on the bike and in the gym was not the very best way to increase my FTP. I'll be thinking about how to make improvements and then implementing those changes in the winter of 2018-2019. But those forecasted improvements aside, it turns out my 2017-2018 plan was effective without requiring excessive hours on the trainer and I learned much more than I anticipated along the way, a nice bonus. Since leaving Deutschland and entering the amatuer racing circuit in Colorado I've had three top-of-the-podium finishes in my very competitive 40-49 age category, a first place finish overall at the Salida 720 racing as part of a pro-expert duo team, a solo fifth overall at the Bailey Hundo, and most recently a solo 7th place overall at the Breck 100. A few weeks ago when I climbed off the bike in Bailey, Colorado I knew I'd accomplished something very special for my modest, endurance-distance, racing palmeres, a breakthrough performance that was made possible by planning and hard work over the winter and the kindness of others that were willing to share their experiences and knowledge of the sport of cycling. Please check back in to Andre Breton Racing Dot Com for future blogs dedicated to my winter base camps in Gran Canaria and Mallorca among other topics from my 2018 training and racing experiences.

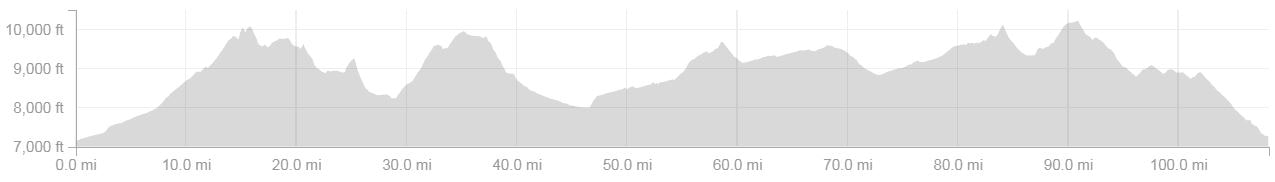

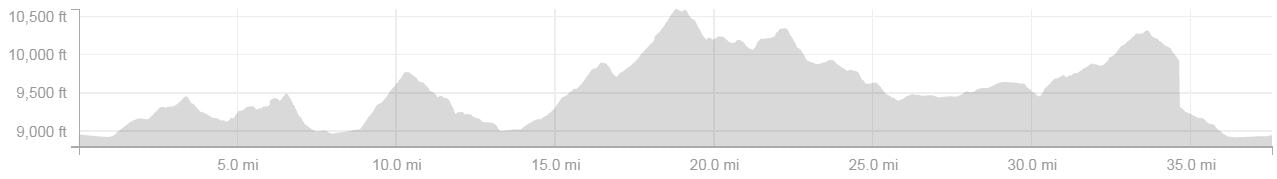

Summary: In this three-part blog-entry I recall my pre- and post-racing experiences at the 2017 editions of the Original Growler (Gunnison, Colorado), Salida Big Friggin Loop (Salida and Buena Vista, Colorado), and the Fat Tire 40 (Crested Butte, Colorado). I also share my motivations for entering the Fat Tire 40, a chance to race amidst an exceptional outdoor community with an exceptional mountain biking history and also very close to a community with the same priorities just down the hill in Gunnison, Colorado. Highlights include a first place finish overall in the ultra-endurance Salida Big Friggin Loop! ORIGINAL GROWLER: 28 May 2017, Gunnison, Colorado  Photo courtesy of Matt Burt photography, 2017 Full Growler, 28 May. Photo courtesy of Matt Burt photography, 2017 Full Growler, 28 May. For the 2017 edition of the Original Growler, half (32 mile) and full (64 mile) routes, Gunnison Trails introduced a new course with even more single track than years before at the expense of (mostly dirt) road sections. Single-track has never been in short supply in this race. The addition of even more, including the technical, rocky, Graceland Trails, ensured that the experience would leave a long-lasting, positive, impression even among the most experienced participants. I had a productive week leading-up to the event, as far as race prep on and off my Niner Bikes Jet 9 RDO. As in the past, this year I was registered for the Full Growler, about 64 miles of racing at Hartman Rock's Recreation Area, scheduled for 28 May. Prep encompassed three days in Gunnison including a visit with a friend, KAO Dave, at the clean, green, and friendly, Gunnison KOA. On the first full day, I rode the entire course (two laps) at (mostly) endurance pace starting from the main parking area at Hartman Rocks. The following day I used my 2002 Toyota Tacoma to access convenient entry-points to session the three most difficult sections of the course along Skull Pass, Josie's, and Rattlesnake Trails. No doubt, training and living at elevation for three days in Gunnison (7700 feet, 2350 meters) was beneficial. And rather than return to Fort Collins after my pre-ride / session work, I instead accommodated additional high-elevation acclimatization by staying in Salida (7100 feet, 2165 meters) for five days prior to the race. Saturday, about mid-day, I returned via Monarch Pass to Gunnison from Salida. I want to thank two friends for their support, Andrew Mackie (Executive Director, Central Colorado Conservancy) for allowing me to camp-out in his living room from Monday-Friday and runner extraordinaire Ellen Silva for crewing for me on short notice including a quick visit on Saturday to transfer bottles, food, and strategy. Ellen was in town to crew for her freakishly fast (aka, "pro") boyfriend that was also competing in the Full Growler. She was very generous to wait close to 30 minutes for me to finish after her primary responsibility crossed the line, he finished 5th overall by the way, legit. A neutral start from town got underway, following a Leadville 100-style shotgun blast, at 7 AM, Sunday morning. Just before the gun went off the pros, among others, were shedding arm warmers and vests. It's noteworthy, based on my experience, that some of these very experienced racers were visibly shaking because of the morning temperature, reportedly 30 F (-1 C) or possibly even cooler, at least one report suggested 28 F. A few degrees aside, it was certainly a cold start even for late May in Gunnison, Colorado. Unlike my neighbors on the starting line, I retained my arm warmers and vest, ultimately I was able to hand-up my vest to a volunteer as I exited Skull Pass on lap one. I held onto the arm warmers to the finish, so often I forget to ditch them when I have the chance, such as when I stopped briefly to resupply water from Ellen before starting lap two. I felt good on the roll-out and stayed close to the police escort, just one bike between me and the bumper, close enough to the elite racers that I was able to listen-in on their conversation, a privilege that I wasn't able to retain for long. When the group reached the right turn onto the dirt at Hartman Rocks I was quickly dropped by the top fifteen or so riders as they raced towards the base of Kill Hill. With an average and max grade of 8% and 22%, respectively, Kill Hill is an effective obstruction for spreading-out the pack. At the top of Kill Hill, the race continued for about 1.5 miles on deeply rutted jeep road before descending onto the first section of single-track, Josho's Trail. My ascent up Kill Hill was slower than my race performances in both 2015 and 2016, 4:34 min:sec versus 4:16 and 4:12, respectively. I didn't feel bad, it's possible I wasn't as warmed-up as years past, perhaps because I've become more efficient at staying out of the wind in a peloton. Despite my slower time up Kill Hill, on the fire road I passed far more than passed me. This set me up, at the intersection with Josho's, to descend onto the single-track with a comfortable space ahead and behind. However, I quickly rolled-up on a group of about five riders as we started the first single-track ascent. No doubt I lost some time getting around these initial riders, perhaps enough to decide my race fate, the 1 minute 24 seconds that I would eventually concede when I rolled over the finish line in 2nd place among 40-49 amateur males (geared). Traffic aside, as I descended and then ascended Josho's, I settled-into an uncomfortable, endurance-tempo pace that I knew I could sustain for many hours with sufficient food and water. Whether or not that pace was faster or slower than previous years is difficult to say, perhaps impossible. My gut suggests I was slightly behind my pace from 2016 and possibly 2015, consistent with my times and overall placement (14th, 17th, 21st overall in 2015, 2016, 2017). Considering I lived for six months over the winter at sea-level, my performance even at the end of May was probably still being affected by an incomplete acclimatization to high elevation (ca. above 7000 feet). But living preferences and acclimatization aside, for the most part I felt strong throughout the race and for that I'm grateful. I'm also grateful that I pedaled away from a high-speed crash that I experienced on the descent of Skull Pass (lap two). On lap two, following a fast descent (only 9 seconds off my PR) of the Graceland Trails, I rolled-up on the wheel of a racer, Andrew Feeney, that would ultimately finish three places ahead of me overall (inside of the top 20). More significantly, before reaching the finish line he'd pass two racers from my age class, one pro, and one amateur, the amateur would finish #1 in the male 40-49 class, which was my goal for the day consistent with my first place, age 40-49 (amateur, geared), finishes in 2015 and 2016. It's always easy, in hindsight, to question what you "should have" and "could have" done, in a race or any other situation that comes to mind. But as all of us eventually learn, as we age, perhaps supplemented by the fabulous book Stumbling on Happiness (2006) by Daniel Gilbert, "should have" and "could have" thinking is replete with pitfalls and misconceptions. Respecting these caveats, I nonetheless cannot help concluding that I wish I'd dug deeper. Over the roughly four miles that remained in the 64 mile endurance challenge, I wonder, looking back, if I had the resources to take back what remained of the four minutes that Wesley Sandoval, #1 finisher in my age class, had taken from me on lap one, and then a bit more. Instead, I watched as Andrew rode away from my wheel shortly after we connected to a short piece of jeep road. As I topped the next hill, by this point on my own, I watched Andrew approach two racers as all three approached the single-track known as Top of the World. Based on finish times, Andrew likely passed them on that section or as he climbed The Ridge. In 2015, unknowingly, I passed my last age 40-49 competitor during lap two on The Ridge, and subsequently crossed the finish line 36 seconds ahead of that individual. My fate was different in 2017, 1 min 24 seconds off the back of Wesley, but that's racing, and #2, despite being the "first loser" as my former coach Alex Hagman once joked, is certainly something to celebrate! SALIDA BIG FRIGGIN LOOP: 10 June 2017, Salida, Colorado There's a lot that's tough about the self-supported (no aid stations, no course markings, etc) Salida Big Friggin Loop (SBFL). An event, like many others (perhaps all) from the Colorado Endurance Series, that's been described as ultra-endurance. As this implies, the SBFL is considered a step above, i.e., harder than, events that fall under the endurance category including the popular Leadville Trail 100 mountain bike race. But rumors and opinions aside, whether or not the SBFL is "ultra-" versus within the "normal" range of endurance-style brutal is probably best decided by a participant that's competed in both events. That's what I signed-up for in 2016 (both events), in 2017 I returned to the SBFL (but not the Leadville 100) for a second time with a goal to win the event overall. This would be my first, premeditated attempt, at actually winning a bike race, part of an amazing, personal and athletic journey from 2013-14, "just finish without being run-over"; to 2015-2016, "see if you can win your age class"; to 2017, "lets see if you can win the whole thing!" In my first rendezvous with the Salida Big Friggin Loop. despite gong off-course for about 21 minutes, I finished 2nd overall just a few seconds ahead of the third place finisher. Ahead of me, by a convincing ca. 45 minute margin, was my good friend and mentor, Ben Parman (aka, "the Parmanator"). In 2017, I wanted to return to the event with the knowledge of the course that I had stock-piled in 2016. I also wanted to deploy a more aggressive, and hopefully effective, water and food strategy. Going into the 2017 race, I felt that if I could keep the air in my tires, stay on course, maintain an uncomfortable endurance-tempo pace throughout, and eat and drink sufficiently, then I had a chance to cross the line first overall. As far as nutrition, plan and implementation, I consumed an original GU gel (not Roctane, too expensive) or Organic Honey Stinger Waffle every ca. 45 minutes. If my stomach was feeling a little too sweet then I went with the waffle, if it was feeling content, neutral, then I went with the gel. Importantly, I started eating right-away including a gel a few minutes before the neutral roll-out from town. At the 2017 SBFL, I raced for 10 hours and 2 minutes, so that's roughly thirteen feeds, combined gels and waffles. As far as calories consumed, my guess is I ate about nine gels and four waffles (total 13 feeds). GU gels are about 100 calories each, waffles about 140 calories, 9x100 + 4x140 = ca. 1460 calories consumed during the race. As of 2016, I've been using only water, no dissolvable mix of any kind, in my Subculture Cyclery (Salida, CO) bottles. For hydration, I started with two 26-oz water bottles which were, in hindsight, not enough for the first 50 miles of the race, Salida to Buena Vista, via the Colorado Trail below Mounts Shavano, Antero, and Princeton. The summits of all three of these peaks exceed 14,000 feet, part of a stunning alpine backdrop that rises majestically from the floor of the Arkansas Valley (Collegiate Peaks Wilderness). If, in the future, I line-up at this event for a third time, I'll certainly stash a water bottle somewhere between Mount Shavano and the base of the Mount Princeton climb. I feel that the only mistake I made, as far as hydration, was not stashing a bottle in this section. The two bottles that I carried from Salida were essentially finished by the time I was part-way up the difficult Mount Princeton climb, a paved and dirt road climb that reconnects racers to the Colorado Trail. Not dehydrated but definitely parched, I was finally able to resupply water at the local tennis courts east of downtown Buena Vista (BV). In roughly two minutes, I drank 20 ounces or more and then refilled my two 26-oz bottles. From here, I ascended to Trout Creek Pass, about mile 68 on the course, before descending to my first, 24-oz, water stash roughly two miles away. The day before the race, as I'd done in 2016, I spent some time stashing water on the back-40 miles of the race course. After a longer descent and some climbing, roughly twelve miles from Trout Creek Pass, I arrived to my main stash, two bottles + six original GU gels stuffed into a water bottle. Much later, at about mile 98 out of 108, I picked up my last 26-oz bottle before the final, significant, dirt road climb. Because of that last 26-oz stash, I had access to water during the hottest part of the day as I navigated (up and down) about 10 miles of single-track through the Arkansas Hills, eventually to the same location in downtown Salida where the race started at 6:30 in the morning, Cafe Dawn. The neutral roll-out (not enforced but generally followed) ends when the pavement turns to dirt whilst ascending from Salida to about 10,000 feet on the slopes of Mount Shavano. Unlike 2016, I decided to keep this section of the race reasonable, not going too deep, but at the same time trying to keep the fastest riders within sight all the way to Blank's Cabin, the start of the Colorado Trail section. I met my goal and felt good on the climb. When I reached Blank's I entered the woods among the top four or five. Subsequently, I was quickly caught and passed before a significant hike-a-bike on a rocky, loose, and steep ascent. But at the top, I quickly regained that difference and rode on to the next wheel. I was probably a little too hot on the throttle after that ascent, but in hindsight I must not have gone too deep either because of how well I was able to maintain my pace late in the race. I caught the lead rider well before the descent into the Mount Princeton Valley, Part-way up the asphalt section of the Mt. Princeton climb the same rider came into view below, but I'd see him for the last time as I approached the Colorado Trail on the upper slopes of Mount Princeton. Throughout the day, even as I was approaching the finish line at Cafe Dawn, I was looking over my shoulder. Many miles before the finish, a look over my shoulder at Chubb Park, not far from the famous South Park, gave me a lot of encouragement towards the conclusion that I might be far ahead, perhaps enough to hold onto the win. Nonetheless, I remained vigilant and on the pedals throughout the day. Because of careful planning, food and hydration, and perhaps backing-off on the opening climb, I suffered much less along Aspen Ridge, ca. miles 94-98, than in 2016 when I was barely able to rotate my pedals on what seemed like endless climbs and far-too-short descents between. For sure, I was hurting in 2017 through Aspen Ridge but it was a hurt that I could withstand without descending into mental anguish and a desperately slow, grinding, cadence. Knowing where I was, how much climbing was ahead, etc, was also a huge advantage relative to my previous experience. At the top of Aspen Ridge, it seemed, based on what I hadn't seen behind me at Chubb Park or elsewhere, that the race was mine to win or lose, all I had to do to achieve the former was maintain a reasonable pace to the finish, enough to stay out front without seriously risking a crash. I wouldn't say I dropped Cottonwood Trail with extreme caution, but I certainly backed-off my fastest pace, especially when approaching rocks that could have easily been my tires undoing. Following that descent, a section that I enjoyed despite how many miles I'd raced that day, I rolled-out of the Arkansas Hills to the palatial view of the Arkansas Valley, Arkansas River, and Salida, below. Soon thereafter, I crossed the train tracks adjacent to town, navigated a fence opening, crossed the F-Street bridge, made a right, and finally, dodged traffic at the last street crossing before rolling to the finish. When I began bike racing back in April 2013, three years after I'd purchased an entry-level mountain bike, my first bicycle since I was about 16 years old, I did not anticipate that I'd eventually find my way to bike racing, doing well as a bike racer, and certainly not winning an ultra-endurance mountain bike event. I'm grateful that chance navigated my journey to cycling and all that the sport has taught me along the way. No doubt, no matter what comes or goes in my life, a small part of that journey, winning the SBFL overall, will remain a fond and often replayed memory. Note, I also won (overall) the FoCo 102 earlier this year, so technically the SBFL was my second overall victory as an amateur, endurance, mountain bike racer. Unlike the SBFL, the focus of the FoCo 102 for the majority of competitors is mainly social, hence my decision to focus, as my first win, more on the SBFL than the near-equal in difficulty FoCo 102. All that said, perhaps I should focus more on the 102 as my first victory? Preferences aside, there is no doubt that my overall win at the 2017 edition of the FoCo 102 will remain, like the SBFL, a highlight of my racing accomplishments and as such, a fond memory. I want to thank Road 34 for developing, organizing, and hosting the FoCo 102, Lastly, I want to encourage any of my readers that might be living in or close to Fort Collins, Colorado, to add the FoCo 102 to their bucket list AND to sign-up for events, such as 40 in the Fort, that will be part of the upcoming, July 21-23, Tooth or Consequences Mountain Bike Festival. Local races are easy to attend, easy on our budget, and most important, they are easy on Planet Earth: far less fuel and other non-renewables are consumed to support our cycling passion when we race locally. Also, if we don't support our local events then those will eventually go away, a sad conclusion. Go online and sign-up today, and tell your friends to do the same. I'll see you out there. FAT TIRE 40: 24 June, Crested Butte, Colorado  Crested Butte, Colorado, widely known for epic, high-alpine scenery, is equally well known for it's mountain biking community, including a very accomplished cohort of pro and elite-amateur racers. And not too far away, a few miles down hill on the only paved road that joins the two celebrated mountain towns, Gunnison is home to an equally respected community of mountain bikers that fill the spectrum from social to high-octane rockets. Early in my mountain biking adventures, well before I initiated training and racing, a friend, Phil Street, generously invited me to visit him in Crested Butte. That was my first visit to the extraordinary backdrops surrounding the town, often referred to as simply "CB". Pretty quick, I was hooked on the views and what I sensed were the priorities of the town, which seemed to favor proximity to nature and outdoor recreation as a good life's highest priorities. Of course, if you favor both then you will likely be very good, given hours of practice, at whatever sport(s) you favor. When mountain biking came into being, in ca. the 1970's, Crested Butte and nearby Gunnison, where people share the same priorities, quickly developed and expanded the sport (Crested Butte may even be the origin of the sport itself, more details). Eventually, both towns would become famous for their feats on mountain bikes, both professional and amateur. Before I departed CB on that initial trip, Phil led me on two rides from town. Despite my pace, well off his wheel most of the time, Phil encouraged me throughout. From CB we traveled down to Gunnison, spent a day riding at Hartman Rocks, where I would years later win my age class for the first time as an amateur, and then drove out to Fruita and Loma for more mountain biking adventures. The whole trip was a breathtaking eye-opener to the scenic splendor of Colorado and areas regarded as some of the very best in the United States for mountain biking. I took it all in, cherished it, and dreamed about the future including returning to Crested Butte. Years later, as I improved as a racer and interacted more with the mountain biking community, I found myself thinking about what it would mean to me to race amidst the communities of cyclists that I'd come to respect, starting from those initial trips with Phillip, in the highest regard. Early-on, I satisfied that curiosity, in part, by competing in the Original Growler in Gunnison, Colorado, for the first time in 2014; and then returning to the Growler in 2015 and 2016, both years I finished first among age 40-49, amateur, competitors (geared). As these details reveal, I accomplished my wish to compete in Gunnison early in my racing career. Along the way, each time I returned to Gunnison, I remembered my similar bucket-list dream to race among the elite up the hill, in nearby Crested Butte. One week before the event was scheduled to start, a teammate mentioned that she was planning to attend the Fat Tire 40 in Crested Butte, part of Crested Butte Bike Week, and she thought that I should come along and throw-down amidst the local and visiting, elite-amateur, mountain bikers. I don't usually race events as short as 40 miles, more typically I favor (and my finish placements do as well) much longer events (65-100 miles). But this was CB and I was eager, as I outlined above, to take part in an event in that valley. My schedule also was open on this weekend (June 24th), that too contributed to what happened next, a hasty decision, all in a day, to sign-up! A comfortable 8 am start and neutral roll-out opened the 2017 edition of the Fat Tire 40. So comfortable that I was even able to weigh-in on a conversation with the fastest guys in the race, including number two finisher of the day Bryan Dillon, USA Pro Team Topeak-Ergon. As I'd done earlier in the year at the Growler, I stayed within the top few racers directly behind the neutral pace vehicle, that is until the car pulled-away and the pro and nearly-a-pro group increased their pace. Following that surge, I dropped, very quickly, to about mid-pack. Along the way, I tried not to think too much about it. Instead, I tried to focus on smooth, efficient, pedaling. Before the race transitioned from pavement to single-track, by now within Mount Crested Butte above CB, I'd made up some ground including a last minute 3-person pass just before my tires made contact with the dirt. By the way, for this event I used the same tires (by now the rear showed significant wear) as the SBFL, Vittoria Saguaro 2.20 front and rear. Overall, I was impressed by their performance in both events, the non-aggressive tread pattern provided noticeably more grip than the tire I traditionally use for training and racing on dirt, Specialized Fast Trak Control 2.1-2.2. However, I'm not convinced that either tire is what I'll commit to moving forward. For the 15 July 2017 edition of the Durango Dirty Century, I'll be rolling with a Maxxis 2.2 Ikon EXO (rear) and 2.2 Ardent Race EXO (front). When racing in a valley with the reputation of CB, no one should be surprised when the trail gets technical. Right away, the opening single-track (Upper Loop to Upper Upper) became festooned with rocks and roots, occasionally broken by short, anaerobic climbs, and longer sections of flow where the aspen trees closed-in and threatened to catch your handlebars. At times like these, when the trail gets technical, I'm fortunate to be from Fort Collins where the trails are often the same. The opening trail allowed me to pass many more competitors. By the time I reached the first section of dirt, I was warmed-up and feeling confident. From Upper Upper the course transitioned to dirt road for a few miles before connecting to the Strand Hill (dirt) road climb. I settled-in as I monitored riders that were coming from behind, when I needed to I picked-up my pace to maintain the gap. The back-side of Strand Hill is a fast descent on mostly, non-technical, single-track. However, just before the exit above the same road, and nearly the same point, where the Strand Hill climb began, is a narrow, steep, washed-out gully in place of where a trail once descended. When I came face-to-face with this unanticipated gulch I was carrying a lot of speed. I tried to shave some of that whilst redirecting the bikes trajectory towards a deeply entrenched trail between two walls of stone. I'm not sure where I failed, but the next moment I was on my feet, the bike was laying between the walls, and I was focused on my right ring-finger. Somehow I'd dislocated the primary knuckle. Later, a teammate with medical expertise, advised that I might have also broken the finger and damaged a tendon. Back to the trail, I felt that I could ride on. I straightened my handlebars, not quite enough in hindsight, and remounted. For about 10 minutes my finger caused me a lot of pain. But as I approached the ascent that would lead to Deer Creek most of the pain subsided and I was able to refocus on the usual endurance-tempo discomforts. Most of 20 minutes went by as I climbed the dirt road up to the Deer Creek Trailhead. From that point, another hour passed as I climbed and then descended Deer Creek through what must be one of Colorado's most spectacular, scenic, landscapes. On either side of the trail, wildflowers, dominated by mule's ear and lupine, inspired vast meadows with their colors as they held fast to steep slopes above and below the trail. Above this wildflower extravaganza, in the alpine zone, I could see deep pockets of late season snow interlaced with extensive talus slope and exposed bedrock cliffs. Below a green forest filled the valleys down to pastures and homesteads. In the same view, Crested Butte's namesake rose from the valley floor in majestic fashion. Despite all of this scenery, I managed to stay inside my endurance-tempo pain cave. And the descent down the back-side of Deer Creek was fast and fun (other than when I reached out to catch a slip and smacked my sore finger). At the bottom of Deer Creek the course returned to gravel, busy Gothic Road. From here, I descended, whenever possible, in the super tuck on my top tube. Along the way I passed at least one more competitor, maybe two. And also, crossed paths briefly with my NCGR teammate, Bill Bottom. He was kindly hauling water bottles up for friends and teammates. Unfortunately, I passed him (opposite directions) with such haste that I missed the chance to get a bottle. At the base of Mount Crested Butte the course returned to single track, and soon the final ascent before the final drop back to Crested Butte and a short road section into town. More than anywhere else on the course, I suffered on the Lower and Upper Meander climbs. I had gone into this race carrying a margin of fatigue more than I would have wanted, ideally, and I think that margin began to take affect on this climb. Nonetheless, I eventually climbed over the top, under idle ski lifts, and began the descent. Right away, my next competitor was directly ahead of me, but as I opened my suspension my rear tire suddenly deflated. As we often do in a race, I tried to ignore my fate, and rolled on for about a minute before stopping to assess the damage. I wasn't carrying CO2 cartridges, only an exceptional hand pump from Lezyne Engineered Design. After searching for a side-wall tear, I didn't find one, I went to work partially re-inflating the tire. Unfortunately, that initial re-inflate didn't last long and I was off the bike a second time, swearing a bit, and trying once more to re-inflate without installing a tube. This one held, not completely but enough to get me to the finish line. At this point in the race, the final miles, it's a pity that I had to stop twice and, in between, shave so much speed to avoid damaging my rear hoop, I think I could have passed, certainly one, and maybe even a couple more competitors on that descent and ride to town. I was feeling good and my descending instincts were firing efficiently after the opening 35 miles of racing in technical terrain. Of course, it could have been much worse, not only the tire incident but also my high-speed crash. So for these reasons, I'm grateful that I even finished, let alone in first place overall among amateurs aged 40-49. Even better perhaps, I finished second among all amateurs and just six minutes off the wheel of the first place amateur finisher. Adding to my accomplishments, I was 19th overall out of 122 including the freakishly fast pros. Getting back to my early experiences and bucket lists, racing in the Fat Tire 40 delivered what I'd anticipated all along, a very special day of racing, a fond memory, and plenty of inspiration for the future; a mangled finger, deflated tire, and other mishaps withstanding, it's all part of the process and part of racing. |

�

André BretonAdventure Guide, Mentor, Lifestyle Coach, Consultant, Endurance Athlete Categories

All

Archives

March 2021

|

Quick Links |

© COPYRIGHT 2021. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed