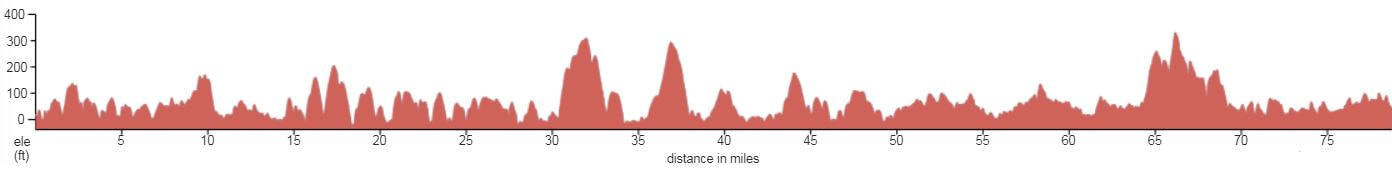

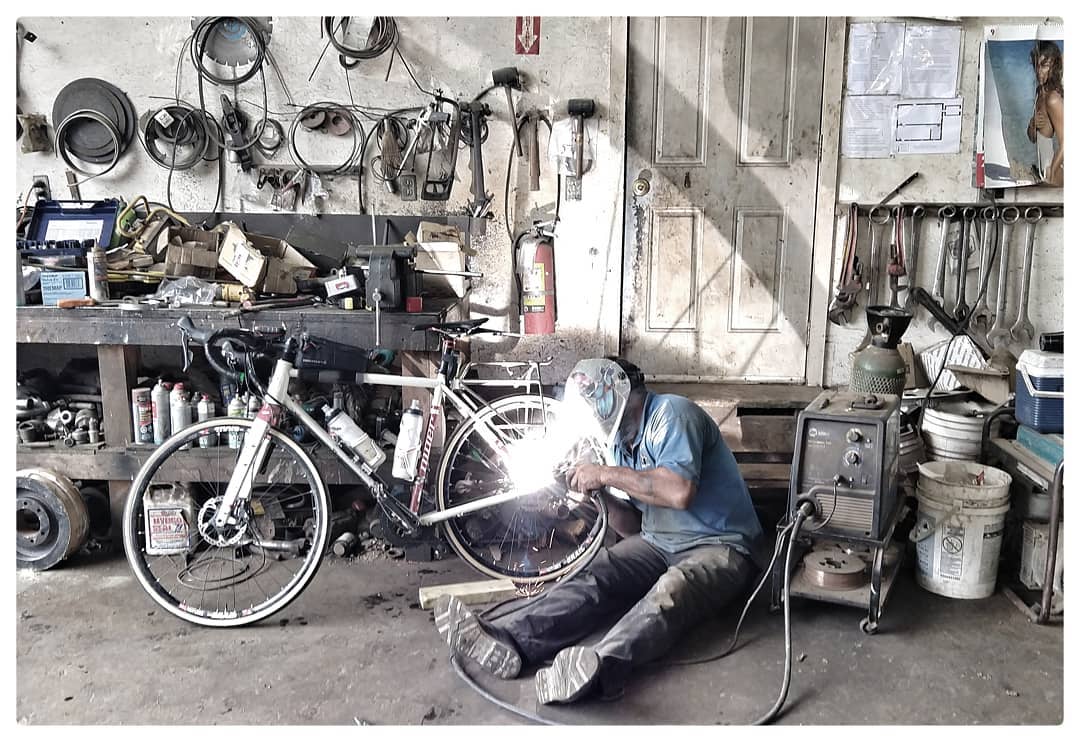

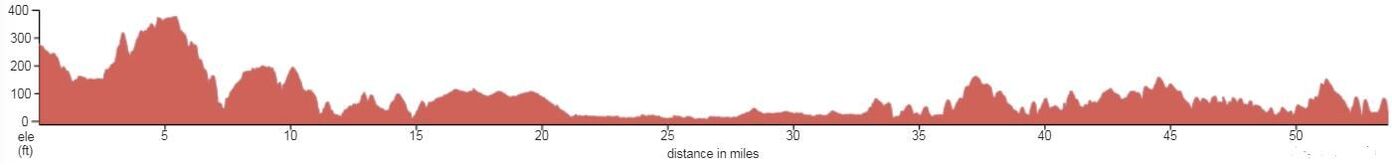

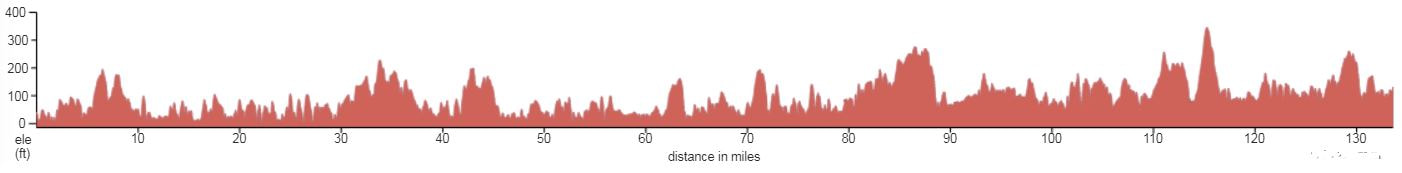

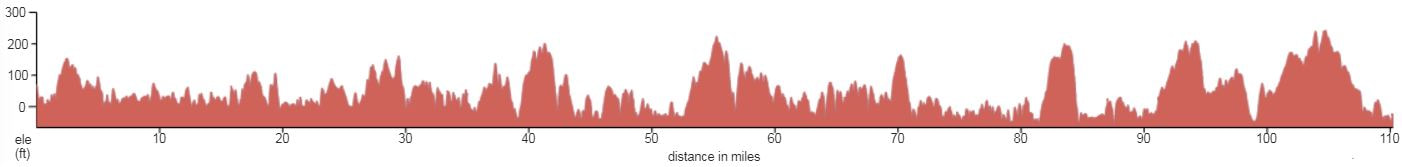

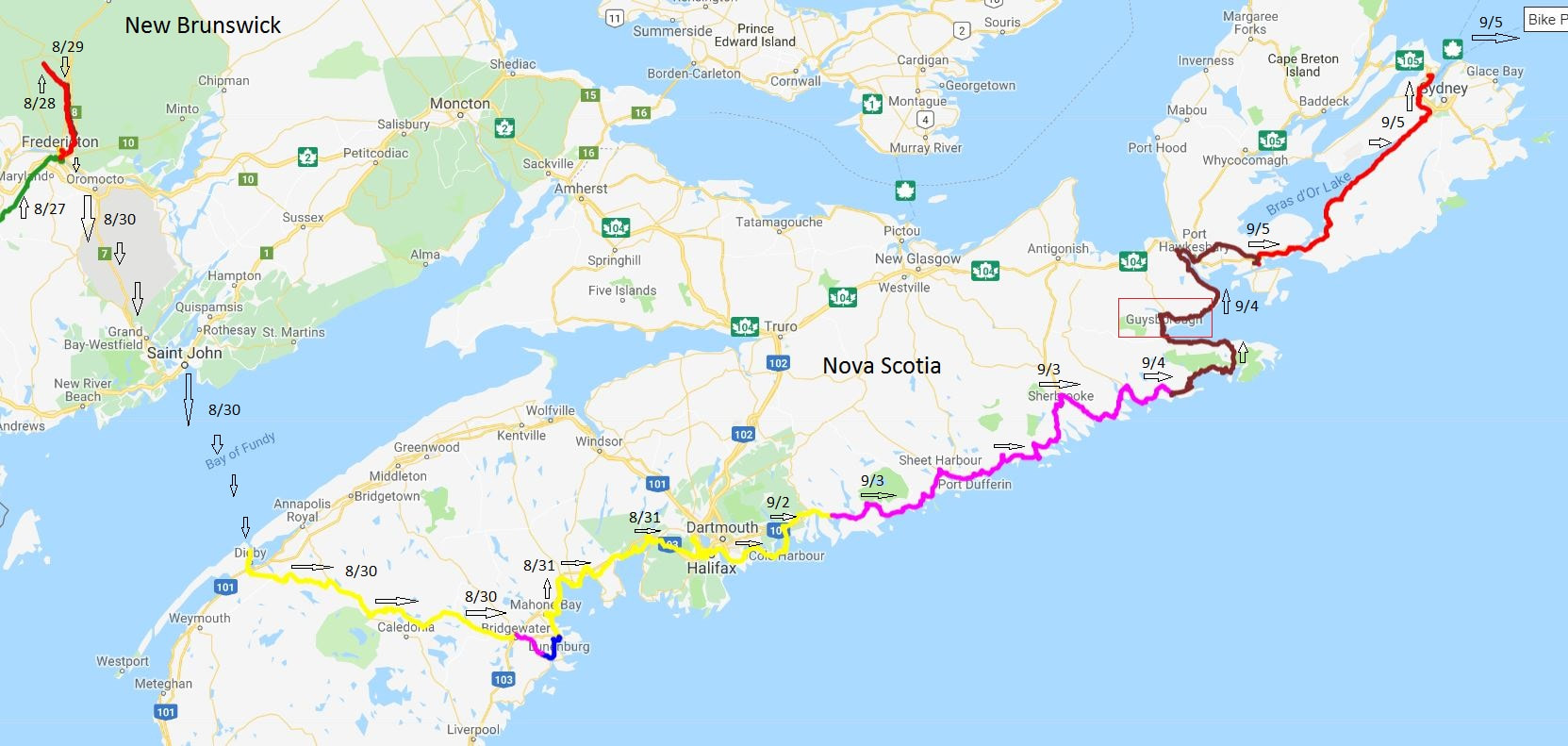

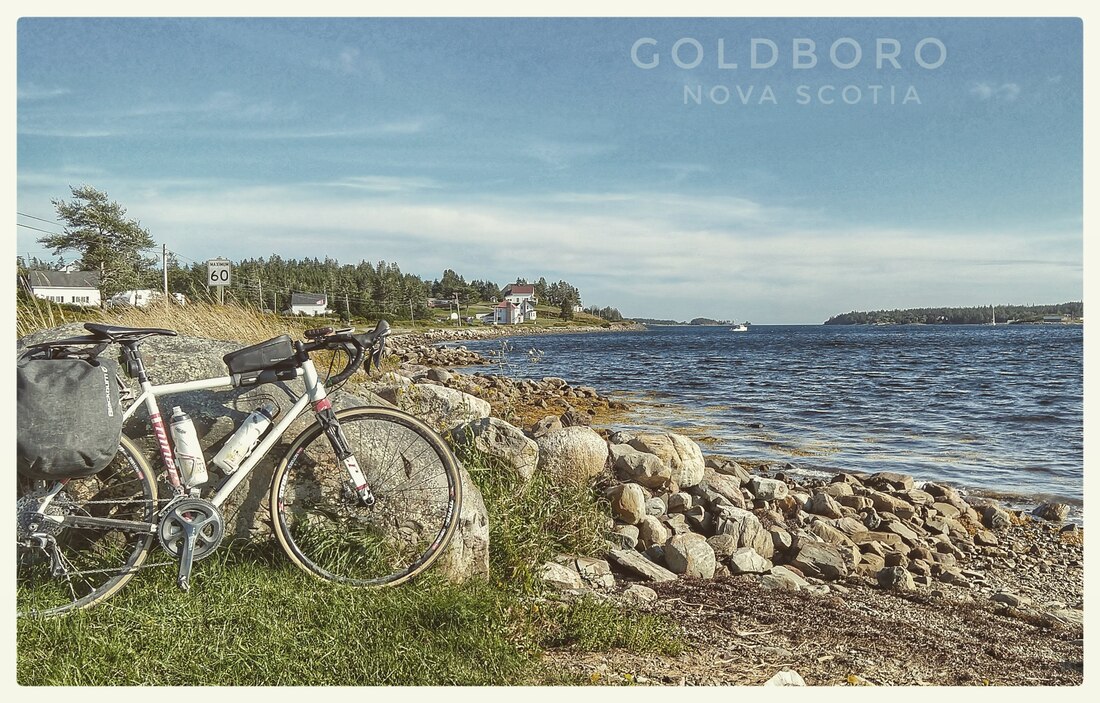

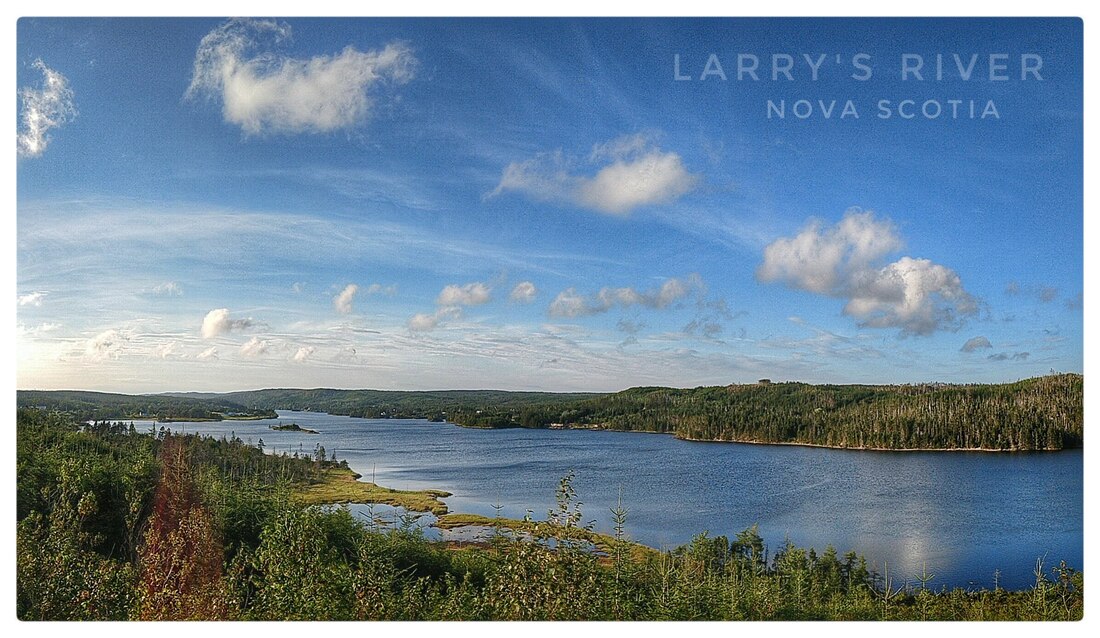

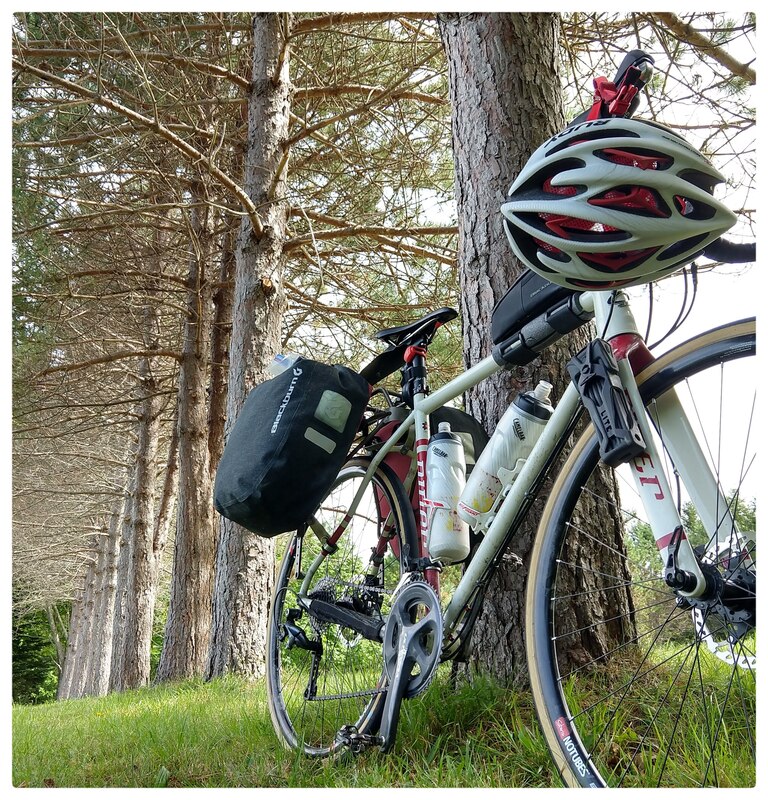

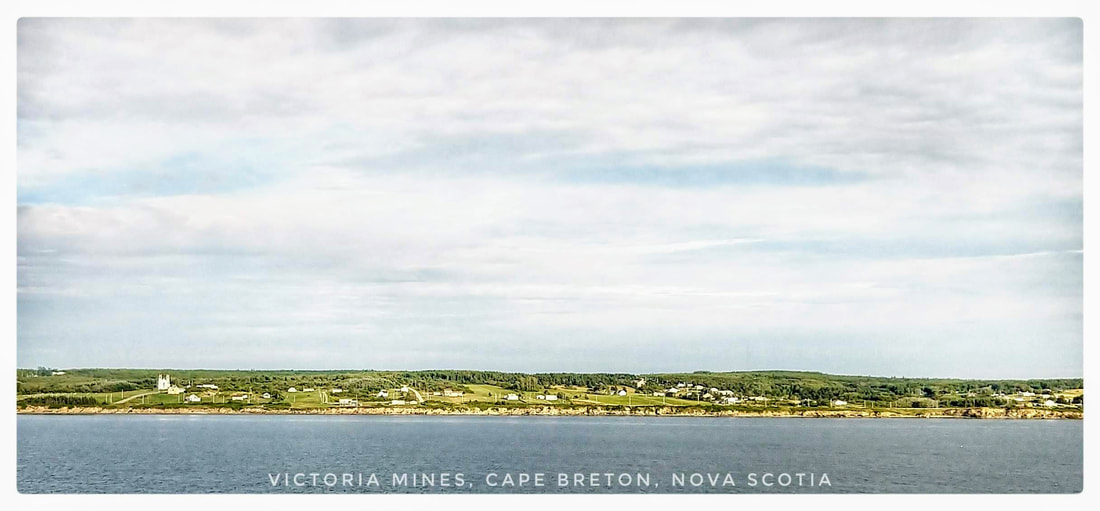

Top-to-bottom: 2 September: 53.6 miles +2569 ft / -2808 ft, Halifax to Head of Jaddore; 3 September, 133.6 miles +7,621 ft / -7,530 ft, Head of Jaddore to New Harbour; 4 September, 110.2 miles +6,918 ft / -7,014 ft, New Harbour to Louisdale; 5 September, 78.7 miles +5,271 ft / -5,246 ft, Louisdale to North Sydney, Nova Scotia. Background: This is the sixth blog entry, the first a prologue, in a series that when completed will tell the story of my 2018 autumn cycling tour through New England (United States) and eastern Canada including Newfoundland and Labrador. Please scroll down this page to read the story in the order that the events occurred starting with my arrival to Maine on 10 August 2018 described in the prologue, Going Full Tilt to Newfoundland and Labrador. Amidst the privileged comforts of Lavi and Saranyan's home in the suburbs of Halifax, I dreamed of unfriendly dogs and remote dirt tracks as Planet Earth peacefully transitioned, in the exceptional loneliness of outer space, into a position in our solar system that signaled a new month on a calendar familiar to you and I and first proposed by the Council of Trent in 1545, when Pope Gregory the XIII served as mankind's primary liaison to God. When I woke it was the 1st of September, 2018, a day closer to an impending autumn but for now the very best, at 44.65 degrees north latitude, for the outdoor pleasure of man, beast, and vegetable. Beyond the shades of my makeshift bedroom, my eyes and other senses were greeted by brilliant blue skies, sunshine, the anticipation of cool temperatures, and no detectable wind. A glorious day, a gift from the cosmos to enjoy by any means including the comfort of Saranyan's passenger vehicle and shoes made cheap by generous factory workers far, far away, where modesty no doubt remains a celebrated moral value. Peggy's Cove is a popular destination for seemingly everyone that visits Halifax. I had their overwhelming recommendation in mind, and Saranyan's generous offer to chauffeur, when I proposed this quaint village by the sea as our primary ambition on a day which I knew we would otherwise spend seamlessly chit-chatting about nearly everything. The drive to Peggy's Cove from Halifax was perfect to open the conversation and soon we were busily drifting between stories from our shared past and topics inspired by scenes just outside and beyond our laminated windshield. Among the latter were many fascinating and easily detectable signs of a very recent glacial past in this part of Nova Scotia including a young coastal landscape reminiscent of places I'd visited farther north, and south, including Newfoundland and Labrador when I traveled there by motorcycle in my early thirties; at that time a graduate student, with Saranyan, at the University of New Brunswick. The coastline was young because until a moment ago, in geologic time, all of Nova Scotia was buried in ice, as Greenland is today, in places the ice was as much as a half-mile or more thick. About 10,000-12,000 years ago, the bedrock foundations of Nova Scotia, and nearby New Brunswick and Maine, were gradually uncovered as the Laurentide Ice Sheet melted faster in summer than it grew in winter, one snowflake at a time from its epicenters in Greenland and the Canadian Arctic. As we approached the coastline driving southwest from Halifax, most of the way on Route 333, all forms of vegetation gradually shrunk towards lilliputian dimensions until all that remained, in dominance, were hardy shrubs and a variety of non-woody plants including seaside goldenrod and salt-tolerant grasses, innumerable blades of grass leaned this way and that way, in sensible submission to the wind, creating a continuum of shades from bright green to grey. Despite the winds absence on this particular day, this physical hardship is no doubt a common occurrence all times of the year on a peninsula that juts south from Halifax many miles into the surrounding Atlantic Ocean. The absence of a forest canopy revealed the presence of boulders, of all sizes, including glacial erratics. These locally sourced and foreign stones, respectively, lay scattered and uncovered, exactly where they were deposited by retreating (melting) ice, as far as I could see, from all perspectives. On the coastline itself, just above the sea, dense beds of non-woody vegetation grew in isolated pockets forming tiny green islands between smooth, polished and even scratched in some case, exposures of the local granite bedrock, a holocrystalline rock matrix of the three minerals, feldspar; quartz; and mica. These Nova Scotian granite formations date back to the origin of the Appalachian Mountains, ca. 480 million years ago when the supercontinent Pangaea was just beginning to form. Feldspar, which appears pink in color to our visual filter, our eyes, is predominant in Nova Scotian granite relative to quartz and mica. Elsewhere, in other parts of Canada and beyond, variations in the composition of quartz and the ratio of the three minerals that define granite create a spectrum of colors including black, grey, and white. When Saranyan and I arrived to the famous fishing village known as Peggy's Cove it was immediately apparent why so many have traveled to this location and why each of them have retold the story of their visit so many times. The village is set amidst the peaceful simplicity and comforting, convergent symmetry of stone and water. Granite domes rise modestly above narrow, salt water channels, easily navigated by modern fishing boats but no doubt a significant challenge for their wind-driven predecessors. Above the water-line, horizontal lines crystallized in my minds eye into wooden docks supporting sheds, piles of wooden lobster traps and other fishing gear. Not far away, the homes of fisher-folk provided the impression of refuge for their inhabitants a few meters above a sea that supports their livelihood and has since the village was established in the second half of the 18th century. The entire community consists of a few dozen homes, twice as many docks, about the same number of sheds, and a myriad collection of fishing boats. From the pinnacle of any of the interwoven granite domes a visitor can easily take-in the entire village in an enviable, sweeping glance including the light house above the town that was built in 1868, the same year that the city of Reno, Nevada was founded. As we departed Peggy's Cove Lighthouse, I proposed a scenic route back to Halifax, along the eastern shore of St. Margaret's Bay, to continue a conversation inspired by landscape, wee fishing villages, and the relative solitude of Route 333 beyond the busy, much loved, intersection at Peggy's Cove. Making our way north, we rolled-through Indian Harbour, Hacketts Cove, Glen Margaret; and eventually into Seabright, Tantallon, and Upper Tantallon. At Upper Tantallon we turned eastward towards Halifax and about forty minutes later drove into familiar suburbs. For the remainder of the day, Saranyan generously introduced me to many destinations in the city, including downtown Halifax, Dalhousie University (established in 1818), and part of the port captured in an image below. The Port of Halifax is an impressive site but even it's spatial footprint and skyward cranes do little to reveal its significance: " ... the Port of Halifax is the deepest, widest, ice-free harbour [in North America], [the harbour] is two days closer to Europe and one day closer to Southeast Asia than any other east coast port; the Port is connected to virtually every market in North America and over 150 countries worldwide." Our tour of the Port of Halifax reached lands-end at Point Pleasant Park, on the south end of the peninsula supporting Halifax, where Saranyan and I settled onto a comfortable bench and absorbed what we could from the here-and-now including the sounds of Arctic terns and herring and ring-billed gulls as they stayed in contact with their offspring and, respectively, negotiated for the best vantage to pounce on any morsel that might be discarded by their human neighbors. Back in the city, in the downtown district, we concluded my tour with forage of our own, an overstuffed pita bread extravaganza for the eyes and taste buds from the Pita Pit on Spring Garden Road, before stopping at Cyclesmith's to pick-up my bike in anticipation of my departure the following morning. The Council of Trent was well aware of the imperfect timing of Planet Earth's rotation, not quite 24 hours, and its effect on so-called 'fixed' dates on their Holy calendar, predominantly the Julian Calendar in those days, a calendar established by Julius Ceaser 46 years before the speculative birth year of Jesus Christ (BC). By 1545, when the Council finally convinced Pope Gregory the thirteenth and indirectly God to sanction a revision, the timing of the spring equinox and, notably, Easter had drifted by roughly 10 days on the Julian Calendar. The discrepancy from 24 hours that caused this and other discontinuities is so small - 23 hours, 56 minutes and 4.0916 seconds - that most of the time we never notice. It's only when we want to attach a date to a particular event, such as an equinox, that our ambitions begin to unravel. Even something as simple in concept as predicting the start of the new year goes awry when the true fraction is ignored in favor of the fairy tale 24 hours. For the mathematically informed, the discrepancy is apparent and obvious and no doubt a source of frustration and who would question that response when we express the true length of a day as a fraction of hours, 23.9344699. I recall Stephen Jay Gould writing in one of his wonderful Popular Science texts, "what hath God wrought!" in response to this fraction, our reality here on Planet Earth and a significant obstruction for astronomers throughout the ages when they wanted to fix any human event to a particular date on whatever calendar was popular in their village. Fractions aside, we can, for now anyway and about the next 3.5 billion years if any of us are still here to witness the last sunrise before life on Planet Earth is vaporized by an expanding sun, be absolutely certain that night will inevitably transition to day each morning following a roughly 24-hour cycle. And that's exactly what happened on 2 September 2018, shortly before I stirred from my second sleep on the first floor of my friend's home not far from the monumental, steel, Murray Mackay Suspension Bridge that rises so far above the land and sea above Halifax that the much more massive Bedford Basin, directly north of the bridge, is transformed, visually, into the impression of a small pond. Friendships are worth any effort to nurture, and with that thought in mind I'm grateful that I had a chance, and made the effort, to visit Saranyan and Lavi, friends that are part of many fond memories from my graduate school days, on my tour of the Canadian Maritimes en route to Newfoundland, Labrador, and beyond. I took my time to absorb the loving energy of my last scheduled visit with friends in Canada for as long as I could before departing into relative solitude on a bike manufactured by Niner Bikes known as the RLT 9 Steel. From Saranyan's driveway, I descended, at about 11 am, into a plethora of fast food restaurants and shopping malls before returning to comfortable suburbs, just beyond the high-speed, Route 102 overpass. Larry Uteck Boulevard did much to settle my nerves, and Kearney Lake Road, which follows the eastern shore of its namesake, dissolved what remained. But inevitably, my planned route, built the night before using RideWithGPS, brought me back into urban traffic and infrastructure, including traffic lights, roundabouts, and construction, as I made my way across the city towards my best option for accessing the coastal route that I intended to follow all the way to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. The Murray Mackay Bridge opened for general use on July 10th, 1970, a fraction of a year before Evelyn Breton gave birth to her second son, a youngster that would grow up with dreams of exploring beyond his childhood half-acre on the corner of North Park and Peck Streets in Franklin, Massachusetts. The bridge spans over a kilometer, 1200 meters, most of a mile, 3,900 feet. At the bridge's highest point, cars, bikes, and pedestrians are 96 meters / 315 feet above a natural salt water channel known as "the narrows" that allows ships of all sizes to access Bedford Basin. Because of its proximity to Europe and narrow access channel, Bedford Basin served as an assembly point for many military convoys destined for battle during both World Wars. During WWII, torpedo nets were installed across the channel to preclude attacks by German Unterseeboots (aka, "u-boats"). Visitors intending to ascend the bridge by foot or bicycle will quickly discover, as I did, that pedestrians are restricted to the south side of the bridge and cyclists the north. I pulled a few somewhat illegal maneuvers when I discovered I was on the wrong side before gradually ascending a constant four percent grade all the way to the bridges summit where I stopped for photos, reflection, and a moment to absorb an exceptional vantage above a town that has generated, and been witness too such as the sinking of the R.M.S. Titanic, more history than most human communities in North America. On the downward-side, I feathered my brakes to avoid alarming any authorities or nearby vehicles passing in opposition to my inspired trajectory. Once in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, just over the bridge, I headed southeast for a handful of miles through an industrial landscape until I reached Shearwater, a burb of larger Dartmouth, where I overshot my exit from road to bike path by a small margin, quickly backtracked, then turned right onto the Trans-Canada Trail. Moments later, I was surrounded by Cole Harbour Marsh. Under my tires hard packed pea gravel complimented a significant tail wind and given these advantages I was easily rolling along at roughly 20 fabulous miles per hour despite the weight of gear, water, and Reynolds 853 steel. The marsh opened up on both sides in an enviable panorama. Occasionally, foot bridges spanned channels that allowed the marsh to flow in unison with each coming and going tide. From Cole Harbour Marsh, the Trans-Canada Trail transitioned into patches of deciduous forest through Lawrencetown before hugging the coast and bifurcating lightly populated, coastal environments including shifting dunes just above beautiful sandy beaches from East Lawrencetown to West Chezzetcook, a distance of about 10 miles (16 km). Not far from the town of Head of Chezzetcook, I transitioned from comfortable Route 207 to not-so-nice Route 7, a relatively high speed, but fortunately moderately trafficked, route that follows the coastline just above alternating bays and peninsulas for many miles. I was occasionally able to take refuge on a parallel road, often dirt, before resuming an intentional, practiced, mind-over-matter calm on Route 7. Using this technique, which avoids building unnecessary tension and discomfort in my shoulders and lower back, I pedaled into and out of Gaetz Brook, Musquodoboit Harbour, Smith Settlement, and eventually Head of Jeddore, above Jeddore Harbour, not far from Salmon River Bridge. Earlier in the day, I'd stopped in Chezzetcook to inquire about lodging along my intended route and enjoy some local fish and chips. Options for the former were already quite thin this far from Halifax, only about 30 miles by path and road, for a guy relying on same-day booking, typically between 4:30 and 5 pm. And this scenario would only increase, fewer and fewer options, as I continued to ride north-northeast as close to the Atlantic Coast of Nova Scotia as I could manage and was reasonable for my ambitions for reaching Labrador in the next ca. two weeks. Perhaps feeling a bit behind schedule after my late departure from Halifax the previous day, the next morning I set-out on what would be my longest distance in a single day from the entire tour, 133 miles, from Head of Jeddore to New Harbour. I slept well at Jeddore Lodge and Cabins and enjoyed every moment of my interaction with the owners of the facility. The night before the lady of the house offered me home-style food and drink from their restaurant and was happy to prepare a pot of decaffeinated coffee just for my pleasure. Of course, the next morning, my ritual, I enjoyed the real thing, "crank" as Joe Johansen called caffeinated coffee when I was an intern at the Audubon Ecology Camp on Hog Island in 1993. By about 8 am, I was on my way and completely focused on the privilege of adventure touring by bicycle. Weather was favorable, including a tailwind that stuck with me all the way to my approach to the Canso Causeway that connects the Nova Scotia peninsula to Cape Breton. Heading west-northwest along that causeway, I subsequently battled a challenging head-wind, but that's jumping ahead a few days from which there remains a worthy story to tell. The 3rd of September, 2018, was as good as any cycling day I've had before or since. An enviable tailwind, remote countryside that only became more-so with each passing mile, and spectacular scenery where the sea and land blended into a tapestry worthy of great artists. From Head of Jeddore I crossed a narrow inlet to Salmon River Bridge and continued on Route 7 for many miles. The character of Route 7 had changed dramatically relative to sections I rode the previous day. And as already implied, that character would only improve, as cars and other vehicles reduced in number with each passing hour. About ten miles into the day I arrived to the town of Ship Harbour and then paralleled, to the south, the somewhat massive and rarely visited I suspect, Tangier Grand Lake Wilderness Area, "[a landscape comprised of] abundant lakes and waterways [that] are enjoyed by anglers and canoe adventurers." Lakes and waterways are tough on a bike chain and difficult to navigate without bridges and ferry boats, none of which were in sight from Route 7, so I stayed on the asphalt amidst a favorable atmospheric current of atmosphere and dust which soon blew me into and out of the towns of Murphy Cove, Tangier, and Spry Harbour, among many others. About ten miles beyond Spry Harbour and not far from the stunning white sand beaches of Taylor Head Provincial Park, I reached an important intersection in this part of rural Nova Scotia in the relatively large town of Sheet Harbour. From that intersection, Route 224 heads north-northwest directly towards the head of the Bay of Fundy, to an inlet known as Cobequid Bay at the top of the famous, for its massive tides, red rock formations, and ancient fossils, Minas Basin. Route 7 dives south-southeast, the route I followed. A few miles from Sheet Harbour, Route 7 intersects with Route 374, a route that heads due north-northeast in the direction of not-so-far-away Prince Edward Island, a much-loved community for residents and visitors just beyond the watery Northumberland Straits in the Gulf of the Saint Lawrence River. The next 55 miles were pure bliss. Despite the rolling, Appalachian topography of the region, the remnants of what was formerly a mountain range as impressive as the present day Himalayan Mountains, I descended into villages by the sea and then rode over the next ridge only to descend again, each time anticipating with excitement the next village and climb rather than growing tired of the repetition. A few vehicles passed by but otherwise I was alone with American crows and other critters that I could detect. Among these, on the forested hills, sounds of the familiar Eastern Phoebe, Red-eyed Vireo, and even the occasional drumming of a ruffed grouse filtered into my conscious mind space and I expressed gratitude, with a grin, on each occasion. I was, as such, never alone. And this is how I've felt on all of my tours knowing, by sound and other signs, that I was in the midst of Planet Earth's wonderful biodiversity, our most precious resource yet one that is nearly forgotten in the current age of myriad gadgets, of all types, sizes, and distractions. Not far from the town of Sherbrooke, Nova Scotia, made famous by Barrett's Privateers, a shanty written by the late Stan Roger's and often sung by every soul on any given night in the bars spread-out across the Canadian Maritimes and Newfoundland, I arrived at the next crossroads where travelers can once again diverge, if they desire, from the coast. At this intersection, I departed Route 7, which heads north at this point directly towards Antigonish in east-central, lower Nova Scotia, and picked-up Route 211, a continuation of the coastal route that I'd been following since I arrived to Middle Lahave on the 30th of August. At Stillwater, I transitioned onto Route 211, by now 93 miles into the days ride. And despite checking my route,at this point I had no idea that I was heading for a ferry, at mile 113, and as such I had no idea if that service would be operating when I arrived! As implied by my ignorance, I proceeded without an iota of concern emanating from my 100 billion or so neurons between my ears, At this juncture, I resumed my tour of the coast on Route 211, descending along Indian Harbour Lake towards Port Hilford from which point I resumed a familiar 'over the ridge' and 'down to the next sea-side village' itinerary. Somewhere on the back-side of about Port Bickerton, I noticed a sign, quite a big one in hindsight, that said something about a ferry but I only glanced at it, I didn't read the full text, and then quickly rode-on. Apparently, my mind was satisfied that my research the night before would not have missed a stretch of water between two peninsulas that were disconnected by any form of bridge or causeway. But in this particular case, it was an instance of Donald Rumsfeld's 'unknown-knowns', when you think you know the truth about something but that truth is actually a non-truth which may or may not have serious implications. In my case, following a fast and fairly long descent, I arrived at the truth and was, as any reader might suspect, totally shocked by what I discovered: I was the only soul on the unanticipated slip and from what I could see equally unanticipated ferry boat, in this case pulled by an undersea cable, was not only alone on the opposite bank but seemingly absent any human attendees or passengers. Sometimes ferry crossings are so small that a hasty assemblage of a cycling route, using RideWithGPS, fails to reveal them. The route drops onto the map, including the ferry crossing, leaving the rider completely unaware that they'll be spending a bit of time on the water. Generally, when this happens rider and bike arrive during a very active part of the day, morning and early afternoon. So there is no concern, just wait for the next boat, and carry-on. In contrast, as I stood in total silence east of Port Bickerton searching for movement or some other sign of life on the opposite bank I also knew that it was well after five o'clock in the afternoon and as such the ferry personal may well have gone home for the evening. The silence was so real, overwhelming, that it took me a long one to two minutes before I started reading the text on massive billboards on my left, water directly ahead. The text had been written and revised several times, which led me to conclude, falsely, that service had concluded at 6 pm, a few minutes before I arrived. No doubt I spoke a few audible words by this point, none of them favorable for sensitive company. I really thought I'd done it this time as we often think or say in English when we're certain there is no way out of a bad situation. At mile 113 whilst standing on a lonely boat slip, I was beginning to resolve a worse-case scenario: returning to mile 93 at Stillwater and riding north from there, towards Antigonish about 5-10 miles before I could access a road that would take me to the bank where the ferry boat was currently sitting idle. Adding to my problems, I'd already booked into a small cabin in New Harbour. Roughly speaking, if that ferry boat refused to budge then I'd be finishing my day well after dark with at least 150 miles in my legs since departing Head of Jeddore at about 8 am. At this critical point, when I thought I was for sure turning around for perhaps the saddest hill climb of the tour, I noticed an old-school phone hanging inside a box juxtaposed between the billboards. This reminded me so much of a similar phone used to hail a ride across the Fox Island Thoroughfare, between Vinalhaven and North Haven, islands I visited in Penobscot Bay, Maine earlier in this tour, that I immediately went in for a closer inspection. Soon I discovered that the phone was intended for use by travelers to hail the ferry boat when the ferry was operating. Still thinking the crew had departed, I nonetheless hesitantly picked up the receiver and began to speak, something like "hello, is there anyone listening?" A moment later the captain responded, and it turned-out that the ferry service ran 24 hours. With great relief, I watched as the boat began it's return trip to my side of the inlet, my cheeks may have hurt a bit from smiling when the boat arrived a few minutes later. Once on the opposite bank, I easily closed the gap, about 25 miles, to New Harbour where my host was anticipating my arrival, a German couple that immediately welcomed me to their far flung cabins and treated me like family. Below I've inserted an image of cabin #1b, in my mind a palatial palace fit for kings and queens with all the comforts a person might desire and more after 133 miles of cycling including one very significant incident involving poor planning, two peninsulas, and a wide expanse of water between. A few minutes before arriving at Lonely Rock Seaside Bungalows, I was very fortunate to arrive at a marvelous view, in perfect early evening light, of the inlet above New Harbour Cove that is technically, according to Google Maps, in the town of Larry's River (see image below). I didn't need any motivation at this point in my tour to continue, fatigue not being an issue especially after two nights rest in Halifax, but the view was nonetheless a spectacular way to end a wonderful ca. 11 hrs of cycling, surprises withstanding, and it filled me with promise of more of the same to come when I rode deeper into obscurity the next day on remote coastal routes. The next morning, following a quick tour of the west bank of New Harbour Cove, I backtracked and resumed my journey on the same road I was already fond of, Route 316, heading east-northeast. I'd picked-up Route 316 shortly after exiting the ferry the night before. Once again, I enjoyed a tailwind in fair weather, mostly sunny skies and warm temperatures, and was so content that I missed a turn which resulted in an unexpected visit to Tor Bay. Tor Bay is the namesake of the bay adjacent to the town, an extensive, partially enclosed body of water that I rode along for 12 miles between Tor Bay and Port Felix East. Like the day before, 'riding along' consisted of climbing over ancient Appalachian hills and then descending into quaint villages over and over again which I was happy to do, feeling as I did at that time that serendipity was around every corner, and it was despite one more significant bump to negotiate. As implied above, my morning and the previous few days had come and gone without incident as far as concerns for the bike. And with it, I'd nearly forgotten about my recent visit to a welder in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, to have one of the RLT's rear rack attaching points repaired. But as I approached the conclusion of Route 316 where I'd pick-up Route 13 heading west, the entire nightmare of a broken bike was put on replay. Close to that intersection the bike began to sway each time I put power into one side of the bike and then the other. Unless the rack bolts had literally loosened and fallen out, unlikely given I checked them every morning, then the new welds had likely cracked, and they had. A handful of miles from the intersection, I pulled off Route 13 into the peaceful, off the road solitude of a small graveyard. I leaned the bike against a white birch and took a moment to consider my options. During this short hiatus from progress, I lapsed into the thought, for about five minutes, that this was likely the conclusion of the tour, far short of my ambitions. But without any option but to go somewhere, raising the dead for assistance being an unlikely solution, I rigged a temporary repair to minimize the swaying and continued west. About one mile farther along, by this point looking directly behind my right shoulder, I came upon a fabrication shop where trucks and construction equipment, like Caterpillar's D-10 bulldozer, come to either be fixed or parted-out. I made a quick u-turn and coasted into the midst of a group of men dressed in coveralls, all of them covered in grease and dirt, the primary material used to surface their parking lot, as they were cutting steel points off the leading edge of a bucket that was still attached to a large digger. Just beyond the gang of three, behind a large workshop, were the bodies of many parted-out vehicles. The bay doors of the shop were open, inside tool boxes and tools were stacked on benches, sometimes three deep, along the perimeter. The walls were also festooned with hanging tools. Here and there a calendar of topless women, of the full-on eye candy sort, provided color where there was otherwise only the dirt and grime of a work area that had seen many hard hours of labor sorting-out and completing difficult tasks involving very heavy equipment. There was no doubt in my mind that a welding machine, perhaps many, were in the mix somewhere. Nonetheless, I was wearing Lycra and barely dusted when I coasted-up to the men doing the cutting. To say the least, they were surprised to see me, especially at such close proximity. To their credit, my new community listened with genuine curiosity as I explained and pointed-out the issue that I had, then asked if they could by chance attempt to repair the problem and right away. Each of them had a cell phone conveniently lodged in one of the deep pockets of their coveralls and using this method one of them quickly raised their supervisor which in hindsight must have been nearby. About ten minutes later, possibly less, Derek of Guysborough, the name of the town where both the graveyard and the shop are located, rolled-up in a pickup truck fit for the scene. He slid sideways out of the truck, once he closed the drivers door I could see that he was carrying a large jug concealed in a brown paper bag. He walked directly up to me and his crew, spoke only a few words, and revealed nothing more via facial expression. Following a brief moment of silence, I repeated what I'd told the gang of three and Derek listened with the same curiosity. I concluded my tragic tale involving a cyclist, his bike, and ambitions to reach Labrador with words that went something like, "So do you think you can fix it?, I'll pay you of course." Honestly, I don't recall Derek saying anything at that point, he simply went to work on the bike and the damage. Eventually, after spending some time primarily welding and grinding with the bike upright, leaning against a bench, he paused for a refreshment and then resumed the job. In the interim, he threw a sheet onto the shop floor and gently rested the RLT onto its drive-train side. The sheet was as clean as any I've slept on, where he found that amidst a seasoned shop I didn't notice and could believe was made available by Holy intervention. Regardless, what Derek of Guysborough lacked in words he certainly made-up for in kindness. About 30 minutes into the project, by now with the rear wheel removed, Derek looked down at the repair and expressed a subtle satisfaction before speaking, a rare thing if you haven't sorted that out by now, "now what about the bracing." I'd asked him if he could not only fix the weld but also fabricate braces for either side of the rack to relieve some of the weight from the attaching point that had failed twice in ca. 1200 miles. For this part of the job Derek recruited one of the gang of three and soon they were cutting strips of stainless steel from sheet stock pulled from the graveyard outside of the shop. They cut, then smoothed, bent and drilled those pieces. Once satisfied, they dug into their bolt and other stock until they had what they needed to mount the fabricated braces between the rack and the seat stays, close to the rear wheel. The solution gave the impression that I wouldn't have any more issues with the welds associated with the rear mounting pins, and that turned-out to be the case, in hindsight. At the conclusion of the job, sheet still lying on the floor, RLT leaning against the right side of the bay door looking into the shop, everyone stopped to stand around for a final assessment of rider, a stranger from a strange land and culture, and bicycle, a modern form that they marveled at to some extent. Derek was among them, by this point, start to finish, he'd spoken a total of about 15 words. His crew was by no means chatty, but they offered many full sentences in response and even unsolicited. Not long after I offered Derek cash for the job and he declined my offer, he spoke his longest string of words that I'd heard since he arrived, "Alright, get out of here." It was, despite his word choice, a massive compliment coming from a guy that I came to respect as much as any other mentor in my life, past or present. It was his way of saying good luck on your tour and in life in general, it's been good getting to know you. I rolled away, as instructed, as the gang of three quickly returned to their hunched-over positions and resumed work on the digger parked just outside the shop bay door. I departed full of gratitude and the renewed hope of a successful tour, my most ambitious to date, and simultaneously felt the effects of a natural chemical cocktail produced by my mind and body that such positive encounters always produce. In this enviable state-of-mind, I easily closed the gap from Derek's shop to the town of Hadleyville, a distance of about 30 miles, where I followed the contour of Route 334 as the road gradually turned left and came-up alongside the Strait of Canso and from there sustained a west-northwest trajectory towards the Canso Causeway, the only dry route from lower Nova Scotia to the island of Cape Breton. For the next 15 miles I patiently, most of the time anyway, rode directly into a strong headwind. Along the way and generally hunched over, I passed through Middle Melford, Steep Creek, Pirate Harbour, and Mulgrave. At Aulds Cove, I arrived at the Causeway and with some intimidation, because of traffic and cross-winds, made my way out onto a road built on earthen fill split by a bridge in the middle that allows the tides to pass by the causeway, unrestrained, four times daily. On the opposite bank, officially on Cape Breton, I stopped for a few minutes in Port Hastings to search for lodging and a good price for my unimpressive budget. I found a suitable option in Lousidale using the AirBnB smartphone app, 23 miles from my location. A few miles down the road, I grabbed a snack at a convenience store in Port Hawkesbury and then resumed my tour, towards Louisdale, on busy Route 4. When I arrived I was 110 miles into the day, since departing New Harbour, despite an hour or more spent with Derek and the gang of three. In Louisdale as the sun was setting, I stopped to ask some locals, two friendly ladies, what my food options were in town, bleak but sufficient, I made my way to a restaurant nearby where I devoured a hot meal then a second, much to the surprise of the waitress. Before closing the mile-ish gap to my bed for the night, by now well past dark-thirty, I purchased heavy whipping cream, for my morning coffee, at a gas station next door to the restaurant. Heavy cream is often sold in a small container and it will do in a pinch, or as a preference, especially when calories are in short supply. The next morning, I backtracked to Route 4 and then made my way east to St. Peter's where I crossed a narrow, seemingly delicate, isthmus that separates the inland sea known as Bras d'Ore Lake from the Atlantic Ocean. The lake is a spectacle to behold, "it [covers] an area of approximately 1,099 square kilometers, measures roughly 100 km in length and 50 km in width." The extensive lake shoreline is "surrounded almost entirely by high hills and low mountains", remnants of the formerly grand Appalachians. My ambition for the day was to close the gap to North Sydney with plenty of time to pick-up my tickets at the ferry terminal, purchase a coffee, and line up for departure to Argentia, Newfoundland. Along the way, I was also hoping to relive the memories of my first visit to Bras d'Ore Lake, by motorcycle, when I camped along it's western shore and was so convinced that I was looking at a lake that I cooked my pasta in what seemed to me to be fresh water. When I took the first bite I was quite surprised, and I never forgot my arguably foolish mistake. At Soldier Cove, Route 4 comes close to the lake shore and from this point to East Cape never strays far. Along the way, I enjoyed many views of the lake from my bike saddle as I pedaled through the towns of (among others) Irish Cove, Middle Cape, Big Pond and eventually East Cape, the terminus of one of the Lakes many arms where I found a graveyard, separation from the road, and solitude to enjoy a makeshift lunch. In the next town, Sydney Forks, I diverged from Route 4 onto Blacketts Lake Road and then Coxheath for many miles before turning left onto Mountain Road which began with a significant climb. All of these roads were weather-worn but otherwise wonderful alternatives to the frenetic energy I left behind on Route 4. Beechmont and Frenchvale provided a few more miles of tranquility before I arrived to the outskirts of the busy port town of North Sydney, Nova Scotia. However, with only 6 miles to ride from the end of Frenchvale Road to the ferry, my primary goal for the day was also in the bag so I wasted no energy at all, on stress of any kind. Within an hour, including a grocery shop, I was lined-up with the other passengers, a cup of coffee from a nearby Tim Horton's in hand, awaiting cues form the crew to ride onto the car deck of a massive ferry. By roughly 4 pm loading was underway, and by 5:30 pm, on schedule, the ferry was gradually pulling away from the terminal en route to the open water between the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the Atlantic Ocean, a turbulent area of cross-currents and mixing known as the Cabot Straits. In my next blog entry, I'll pick-up my adventure from the ferry terminal in North Sydney, Nova Scotia and take you with me across the Cabot Straits to the terminal at Argentia, Newfoundland, on the famous Avalon Peninsula. From Argentia, I'll recall my tour of Newfoundland, including visits to far flung Bonavista, Twillingate, and Fogo Island. As well as a double-flat that I experienced when I hit a hand-sized stone at high speed whilst riding alongside an 18-wheeler traveling at highway speeds. I'll wrap-up the entry with my experience hitchhiking several hundred miles on two tractor trailer trucks. Those rides brought me to Saint Barbe, Newfoundland in time to catch a boat to Blanc-Sablon, Quebec and nearby Labrador, where I subsequently climbed onto a cargo ship that brought me, over four days and three nights, to Rimouski, Quebec. Cyclesmith's in Halifax, Nova Scotia before and after repair photos; on the right the RLT is ready to continue the journey with new tires and chain as well as a general tune-up, 1 September 2018. East Bay, Nova Scotia, in the privileged refuge of a graveyard where I enjoyed a brief lunch, 5 September 2018. A view from my cabin and the deck of the ferry from North Sydney to Argentia, 5 September 2018.

10/11/2019 08:42:36 pm

Hey Andre, looks like you're having an AMAZING adventure! BTW, the dates in your blog are 2018, but I think I'm reading the trip you're on now. 10/13/2019 07:58:45 am

Thanks Vicky! I sent you a message using FB messenger. What you commented on is a segment from my 2018 tour, my 2019 tour is all in Europe. Under Travelogues look for Duncansby Head to Istanbul then Le Tour de Europe as well as individual pages for countries and units within. I'm looking forward to seeing you when I get back, roughly 29 Oct, to the US. Comments are closed.

|

�

André BretonAdventure Guide, Mentor, Lifestyle Coach, Consultant, Endurance Athlete Categories

All

Archives

March 2021

|

Quick Links |

© COPYRIGHT 2021. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed