The Belgrade Lakes to Calais, Maine including sixty-three miles of gravel on Stud Mill Road.5/31/2019

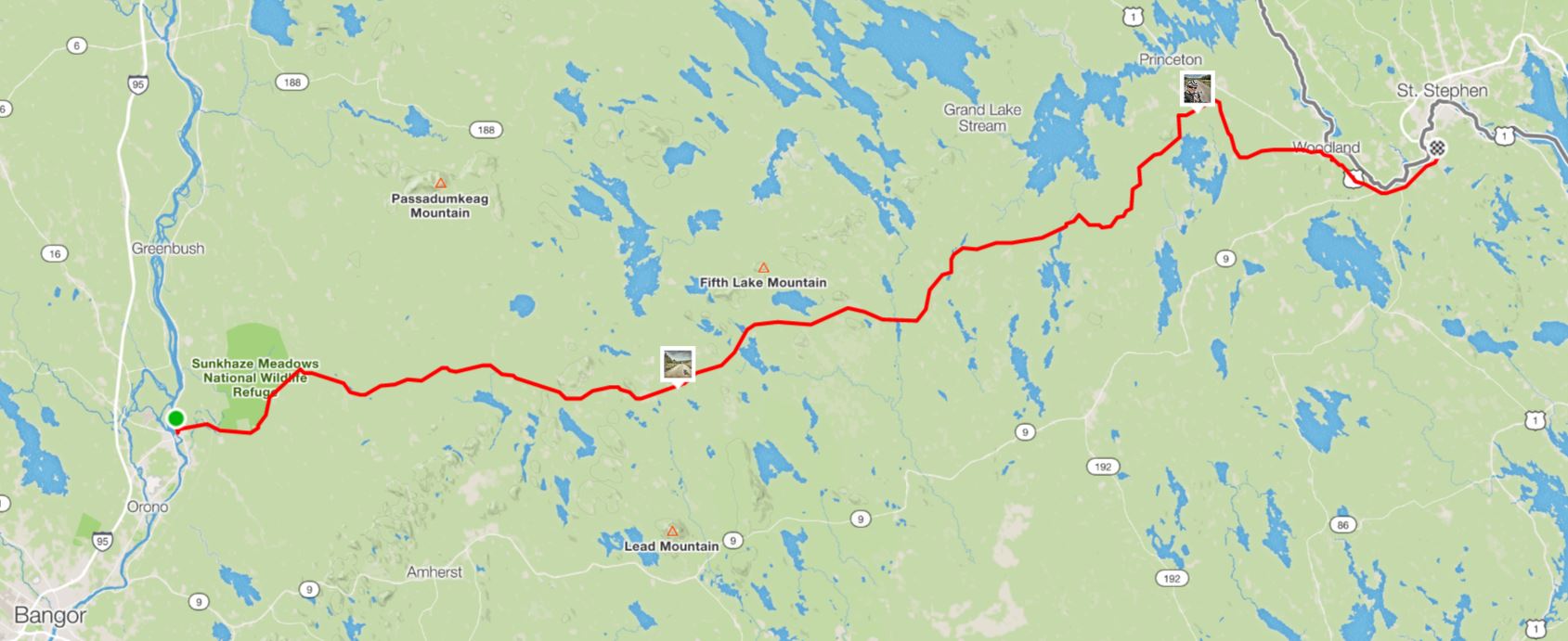

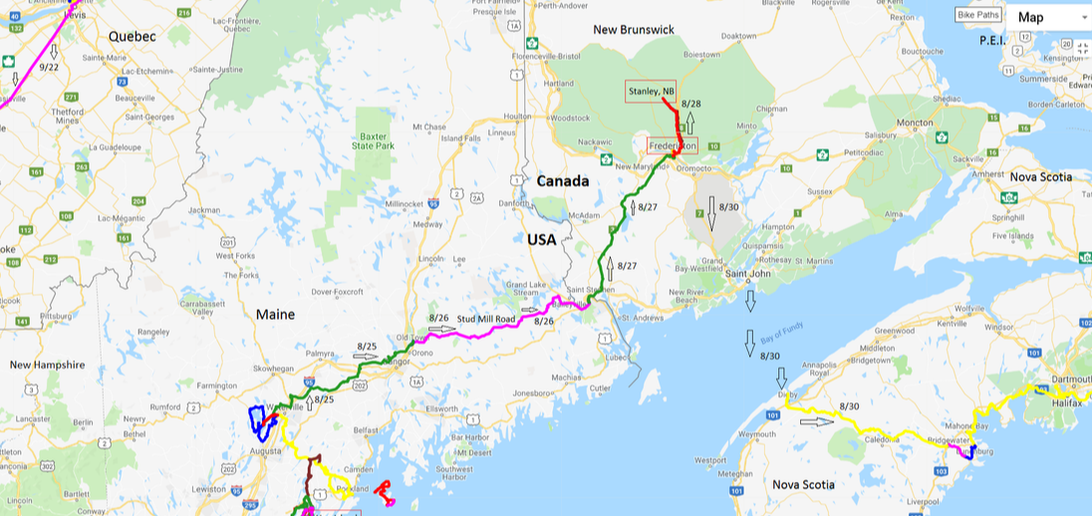

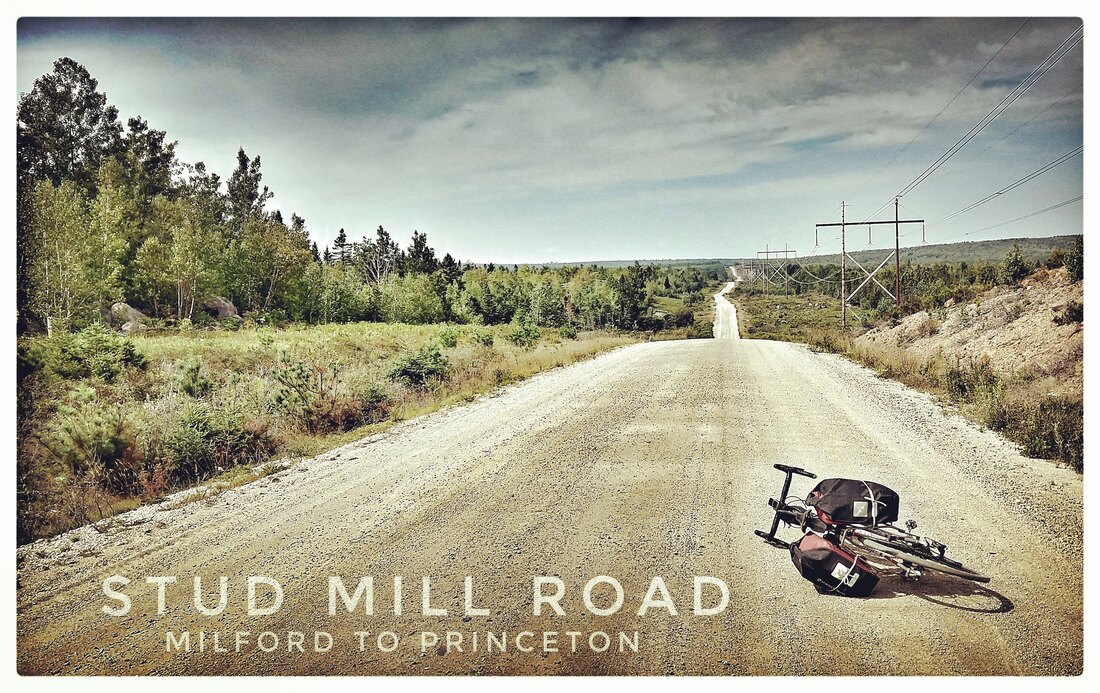

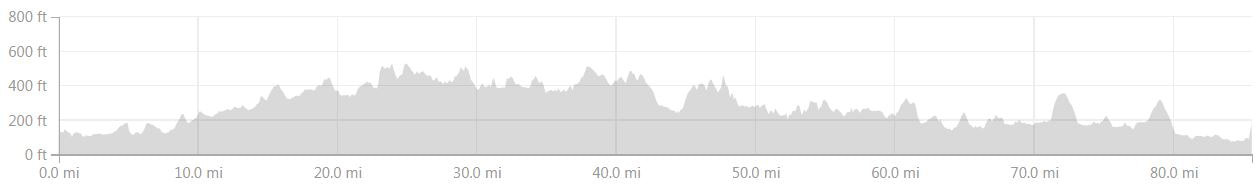

Milford to Calais, Maine, 26 August 2018. Most of the route is on Stud Mill Road (elevation profile above). The opening few miles are on County Road in Milford, the last few are on South Princeton Road (dirt) and Route 1 (asphalt) in Princeton and Calais. Note the small boxes, these are the locations where I photographed the bike lying on Stud Mill Road (left) and me with my sunglasses dipped on my nose (right), both images are included in this blog entry.  My route from the Belgrade Lakes Region to Milford (8/25), Maine, then (pink line across the middle of the image) across Stud Mill Road to Calais, Maine (8/26). When the route turns north, I'm almost immediately in New Brunswick, Canada (8/27), starting at the border in Saint Stephen then north to the provincial capital, Fredericton, and eventually (8/28) Stanley at my northern most ascent. I've also included my route from Fredericton to Nova Scotia via a ferry across the Bay of Fundy. As well as a part of my route from 9/22 through Quebec. I'll write about these bonus routes elsewhere, here they are provided only for perspective. Background: In this blog entry, I pick up the story, from my previous entry, at my departure from Messalonskee Lake in the Belgrade Lakes Region of Maine where I stayed for three nights at a friends cabin. This is the third in a series of entries, the first a prologue, that will tell the story of my autumn 2018 cycling tour through the Northeastern United States, Canada's Maritime, Newfoundland, Labrador, and Quebec provinces. I hope to finish the massive writing project before I depart on my next tour, John-O-Groat's, Scotland to Istanbul, Turkey, ca. 20 August 2019. One half of my genetic story, involving a great grandfather of French descent, the other was a Scottish immigrant that settled in Kansas, may have included the nearby town of Waterville, Maine. Henri Breton, his wife, and two children certainly immigrated from France to Canada then, within a couple of years or less, migrated to and settled somewhere in northern Maine ... That much I know from letter correspondence with my grandfather, Joseph Breton, before he died. In those letters, Grandpa Breton, as I knew him, mentioned Waterville as a place where Henri ("on-ree") might have settled, but his confidence was understandably low given that he was orphaned at a very young age (two years old comes to mind). In the opening chapter of his life, he's with his sister on a train bound for a Catholic orphanage in Cambridge, Massachusetts from possibly Waterville. Grandpa Joe spent his youth in that orphanage, he was raised by, apparently, unfriendly nuns, he finally left the system and started his own life when he was 17 years old. Having all of this in mind and nurturing a curiosity that, even during idle distraction, never seems to be in short supply, I had thoughts about stopping at one or more local government offices in Waterville to ask questions about Henri and my great grandmother. This was on my mind as I departed Tanya's cabin and the forest above Messalonskee Lake in Belgrade heading north on Route 11 towards nearby Waterville but autumn's proximity and curiosity of another form won the day and I instead skirted the largish town and was soon closing in on a bridge over the Kennebec River in Fairfield, Maine, a few miles upstream of Oakland and The Green Spot where days before I was welcomed by Tanya her sister. On my journeys by boot, boat, motorbike, and bicycle I've always been fascinated by rivers. Not the smallish ones per say, but those that were carved-out as special by early natural history writers, such as Alexander Von Humboldt, and given a significance through their words and hand-drawn sketches that underlie our modern impressions. The mighty Amazon is certainly near the top of this list, and others easily come to mind including the Nile, Rhine, Ganges, Saint Lawrence, Hudson, and Mississippi. Not far below these giants among the worlds waterways are many more rivers, some of them also quite famous, among them the Kennebec, an Abenaki name that means "large body of still water or large bay" referring, I assume, to the large freshwater bay above Bath, Maine where the Kennebec captures the Androscoggin River. Alternatively, the Abenaki might have been referring to the saltwater bay above Popham Beach, the location of the early European settlement (1607) of the same name. Just beyond the dunes at Popham Beach, the Kennebec peacefully relinquishes it's sediment load and remaining energy into the sea, 170 miles downstream of it's headwaters at Moosehead Lake. The French navigator and cartographer Samuel de Champlain was the first European to describe the Kennebec, in writing and maps, from Popham Beach to as far north as current day Bath. Within two centuries of Champlain's visit, Bath would become known as "the city of ships" for it's prolific ship building which has continued, without disruption, up to the present. Now-a-days, Bath Shipyards builds the latest stealth warships for the US Navy. I saw no evidence of a stealth warship as I crossed the bridge in Fairfield, a middle-sized town, a good thing given the shallowness of the river this far north of Bath. However, as I pedaled my bicycle between the banks of the Kennebec, my mind easily drifted to thoughts about centuries of trade and navigation, by countless forgotten people that lived-out their lives, many of them close by, traveling by paddle, sail, steam, combustion, and most recently, nuclear fission up and down this river. If the Kennebec could speak the sounds of every voice that passed by this juncture, long before there was a town of Fairfield, then I suspect I would be simultaneously overwhelmed by the dullness of the chatter (very little recognition of a bigger picture or conclusion) and the collective realization of so many human stories. Fathers and their children, warriors, slaves, administrators, all of them passed this way. Crossing a historic river like the Kennebec always gives me pause and immediately after many hours of inspired, contemplative, day-dreaming. I rode into farmland on the north bank of the Kennebec, rolling Appalachian hills and valleys supporting fields of mostly grass hay and corn, feed stock for what remains of a dwindling American dairy industry. Here and there, patches of forests, silos, barns, and farm houses, filled the gaps in an otherwise agricultural landscape. From the east bank of the Kennebec and Fairfield, I briefly headed north before assuming my overall trajectory to Milford, primarily east-northeast. A few miles past interstate 95, still within sight of Fairfield and it's bridge, I overshot a right turn that according to RideWithGPS would take me towards Clinton, Maine. During moments like this one, I typically forge ahead, preferring to freelance until I arrive, by forward versus backward progress, onto my intended route for the day. Nonetheless, in this case, no need for haste in sight, I reversed direction and quickly located what turned-out to be a tractor track signed no trespassing. A quick inspection of the area using my Garmin eTrex20 GPS (zooming in and out) suggested the rough, deeply rutted, dirt two-track ahead would be a short adventure before I transitioned to a marginally more popular route, likely an asphalt surfaced road. That gave me confidence and a moment later I plunged into obscurity, between the lines of corn and sometimes into the mud that was favorable relative to the bike swallowing ruts created by years of tractor use. A few minutes into a real but hardly noticeable trespassing anxiety a few homes came into view, shabby, run down, the sort of places that celebrate dangerous dog breeds and the absence of a leash. I crept-up on the first, then the second, then onto the anticipated asphalt, picked-up my pace and continued without incident. Along the way, a neighbor picked-up their head and we exchanged hand waves. Despite the long history of navigation and trade on the nearby Kennebec River, I suspect my presence was a rare event and some speculation may have followed, at the dinner table, and perhaps into the next morning. No doubt my skin tight, Lycra, bike kit from Primal Wear contributed to the tale. I rode on to Clinton without any additional tractor tracks or no trespassing signs to negotiate and then continued without stopping to Burnham where I missed my chance to explore Patterson's General Store and Museum, a classic off the beaten path resource and local favorite. An easy baseball throw from Patterson's, I guided my Niner Bikes RLT 9 Steel through a right turn onto a bridge, onto Troy Road, and crossed-over the middle-sized, slow flowing, and scenic Sebasticook River, a tributary of the Kennebec. Troy Road was a pleasure to explore for many miles, initially uphill from Burnham before leveling off, paved but always rough from tough winters, pot holes, fractures and other surface non-pleasantries constantly challenged the guy sitting on tubeless, Hutchinson Sector, 28 mm tires. A few miles out of Burnham, I hailed a stranger on his riding lawn mower and asked, kindly, for water. A few minutes later, I was telling stories to his wife and children in their driveway, they were shocked that I was planning (hoping at that time) to ride from their home all the way to Labrador. Not long before the social water stop, I'd stopped to pick a few apples from an abandoned tree, no doubt part of a much larger, now mostly gone and forgotten, orchard,. As I chatted, I did my best to politely nibble on nature's bounty. The same habit, picking stray apples, fueled (in part) many of my autumn cycling rides across Northern Germany when I was living part of the year in Hamburg. Beyond the familiar American smell of freshly cut grass, I made my way eastward from Burnham and the Sebasticook River to Twitchel Corner, then Dodge Corner, Smarts Corner, Cooks Corner, and Troy Center. Since departing Burnham, I was following, compelled by the road below my tires, the long-axis of a much eroded Appalachian ridge. On either side of the ridge, agriculture and horticulture laid claim to u-shaped valleys, for cows, corn, and grass hay. Between the effects of the plow and grazing animals, a seemingly random patch work of partially forested hills and valleys spread to the horizon, near and far. The view beyond my anonymous ridge was as good as most, despite being in a no-man's land when it comes to the destinations of traveling Americans and visitors. The Appalachian Mountains are an ancient feature of Planet Earth's crust, the top layer of solid rock that floats on Earth's mantle, a plastic layer, similar in consistency to hot asphalt, that exists above Earth's liquid-iron core. The range rises above the adjacent plains in Alabama and continues, unbroken, for 1500 miles all the way to the Canadian Province of Newfoundland and Labrador - technically the range continues, broken by the Atlantic Ocean, even farther, to Scotland, but that story is a bit off course for my North American bike adventure. Curiously, the French territories, not far from Newfoundland's Avalon Peninsula, islands known as Saint Pierre and Miquelon are partially submerged summits of the Appalachian Mountains. The width of the range is also impressive, varying from 100 to 300 miles depending on where the cross-section is measured. Moving from, roughly, the south to the north along the main axis of the range, well known units of the collective Appalachian Mountains include the familiar Great Smokey Mountains, Blue Ridge Mountains, Allegheny Mountains, Taconic Mountains, Berkshire Hills, the Green and White Mountains of Vermont and New Hampshire, respectively, and many isolated peaks including the impressive, from above and below, Mount Katahdin (5,267 ft, 1,605 m) in north-central Maine, a peak that I was witness to, majestically towering over Maine's North Woods, on many days on this tour. The highest peak in the Appalachians is Mount Mitchell in North Carolina (6,684 ft, 2,037 m). Not far below in elevation, Mount Washington (6,288 ft, 1,917 m), is likely the Appalachians most storied peak, the defining, in legend and profile, summit in New Hampshire's much visited and celebrated White Mountains. The names "Apalchen or Apalachen" are the original translations of a Native American tribe that was located near present-day Tallahassee, Florida. These translations date back to the Spanish Narváez Expedition that explored the New World from 1527-1528. The word eventually evolved to "Appalachian", early enough to claim its position as "the fourth-oldest surviving European place-name in the US." Like the word to describe them, the bedrock and geologic history of the Appalachian Mountains are deeply embedded in antiquity. The initial uplift of the Appalachians, an event that occurred during the middle Ordovician Period (about 496–440 million years ago) predates all but the earliest forms of our vertebrate cousins, the fishes. During this time, Planet Earth's seas and oceans were dominated by invertebrates, especially molluscs and arthropods including brachiopods and (the now extinct) trilobites. The orogeny or 'mountain building event' that initially uplifted the Appalachians was the result of plate tectonics, foremost the subduction of the former seafloor of the Iapetus Ocean (Iapetus plate) under North America as Africa approached from the east. As the two continents approached, the saltwater basin that was the Iapetus Ocean shrunk until it was no longer a basin at all, instead a suture between two colliding continents. Fittingly, given humankind's fascination with relations, the legend of Iapetus lives on, in a subtle way at least for those that are interested in the details: Iapetus in Greek mythology was the father of Atlas which is the namesake of the next ocean, the Atlantic, that eventually filled the same gap between North America and Africa when the supercontinent Pangaea began to fracture about 175 million years ago. The Taconic Orogeny was the first of a series of mountain building events that are responsible for our present day Appalachian Mountains, along with the ever patient, ongoing, contribution of erosion caused by, primarily, flowing water but also wind, biological, and chemical processes. High on a crystalline ridge of the much eroded and much reduced Appalachians, on a foundation of ancient Precambrian (>541 million years ago) and Cambrian-aged (541-485 million years ago) igneous and metamorphic rocks, I approached Troy Center where my GPS silently (my preference) sent me northeast to North Dixmont. In this wee but attractive village of mostly forgotten Maine, I crossed the Moosehead Trail Highway without incident. A few miles farther on and I was pedaling north out of Rollins Mills, past Plymouth Pond and a stream without a name, past Fail Better Farm and Tykenbay Acres. A few miles south, I arrived to the relatively bustling town of Carmel, where I enjoyed a hot lunch and a bit of chit chat with the locals. Next, I passed by Stepping Stone Farm, then under interstate 95, by this point heading north on Cook Road. I could have taken Route 2 east from Carmel, but instead I rode a few miles north of town then took a right, close to Damascus, onto Fuller Road. Heading east again, I rode over Black Stream then through more podunk towns, Leathers and Snow Corners. By this point in my journey, I was convinced that everyone from the sleepy parts of inland Maine must have been born and raised on a "corner." From Snow Corner, I zig-zagged my way around the western edge of one of Maine's largest population centers, Bangor, including the cities international airport. Part of the bliss of this route was a low(ish) traffic bridge over Kenduskeag Stream, a tributary of the Penobscot River, namesake of Penobscot Bay from which I'd come a few days before. As this implies, somewhere on my day's tour of the "corners" I'd transitioned from the watershed of the Kennebec to the Penobscot River watershed, these regionally significant rivers drain 5,869 (15,200 sq.km) and 8,610 square miles (22,300 sq. km) of the State of Maine, respectively. From the bridge, I eventually made my way northeast to Stillwater Avenue, with many locals that were also avoiding the traffic of alternative routes, and comfortably coasted into the university setting of Old Town, Maine on the west bank of the Penobscot. After a few photos of the Penobscot and the Milford Dam, I crossed the Milford bridge to the Penobscot's east bank and a moment later I was arriving to the locally owned Milford Motel on the River, my destination for the evening. Not far away, surrounded by the river and well signed as I rode into Milford, I encountered Indian Island, the headquarters of the Penobscot Tribe. The Penobscot Indians have lived in the area for centuries, the first European to visit Indian Island may have been the Portuguese explorer (funded by Spain) Estêvão Gomes in 1524. Samuel de Champlain visited the tribe in 1605. On my way through Old Town, I'd stopped for groceries at one of America's popular supermarkets, which one I don't recall. Back at the motel, I wasted little time getting into a much anticipated meal which included fresh veggies, sandwich meats uncontaminated with toxic preservatives, and the best bread option I could find in the store, possibly a baguette. My meals varied a lot from day-to-day but these were typically purchased in a grocery store to save money and avoid refined sugar and processed foods, the primary ingredients of the Standard American Diet (SAD). Both food additives have been shown to be, literally, deadly by the ever expanding, and enlightening, science of nutrition. Since leaving Belgrade in the morning, I'd ridden 90 miles and climbed just under 5000 feet along the way; here's a link to the ride including maps, elevation gain, and more on Strava. Despite the much eroded and worn-down state of the previously grand Appalachian Mountains, as grand as the Rocky Mountains are today, in this part of the range there were, apparently, still a lot of hills remaining to climb! The next morning I rolled-out at 8:04 AM, according to the record of my ride which I posted to Strava at the end of the day, by then in Calais, Maine; here's the link. At close to 5.5 miles from the Milford Motel, I rolled on to dirt. The initial handful of miles were not reassuring for a mind concerned about the quality of the road between here and Calais. The surface was loose, so-much-so that my tires often dug-in and caused the bike to swerve left and right. I recall about six miles before I arrived to a four-way intersection with Stud Mill Road itself, formerly I was on 'County Road', no other distinction given on Strava maps, that skirted the eastern border of Sunkhaze Meadows National Wildlife Refuge. At the four-way, I turned right onto Stud Mill Road and immediately conditions improved. The road widened quit a lot, and although it remained dusty when a handful of cars and recreational trucks passed-by, the dust was much less than what I encountered on County Road where there was much more traffic, certainly not a lot, but more that showed me little mercy as each driver raced past my, occasionally, swerving bike, no doubt late for nothing. The surface of Stud Mill, at this juncture, was hard-packed without much washer-board or ruts. Small stones were embedded in the matrix but I comfortably rode over or around these obstructions. The road trends due east and the view is generally unobstructed for many miles. From my bike saddle, I could easily see the rolling nature of the road and surrounding forested landscape (broken here and there by clear cuts), a geologic remnant of the formerly much higher and deeper Appalachian mountains and valleys. I settled into a comfortable pace, average speed around 15 mph, my preference on this tour and others. I was anticipating about 60-70 miles of dirt, so a pace of 15 mph would deliver me, baring any major preclusions to forward progress, in under five hours to Route 1 (Houlton Road) on the Calais side, a few miles shy of the Canadian Border. Not long after a short lunch, a sandwich that I ate sitting on a massive rock perched on road right amidst a pair of curious ravens, the road unexpectedly split about 40 miles from Milford. The wide, hard-packed, road I'd been following turned to the north but my GPS track line directed me to continue straight, which I did with only a little reluctance. In hindsight, it's clear from maps that I never deviated from Stud Mill Road. Nonetheless, I suspect there was, and is, a smoother alternative to what I eventually experienced. The opening mile or two, from the split, was reasonable: some larger stones embedded in the surface and some road damage but I could easily ride around all of it and maintain close to an average 15 mph. So far there was no need to be concerned for either the bike or the rider. Then fairly quickly, the road narrowed substantially, the deciduous trees on either side encroached over the road, and the surface quality plummeted to what looked more like a dry creek bed than a single lane dirt road. Fairly massive baby heads were everywhere, i.e., the tops of rocks, sizes ranging from baseball to basketball, were embedded, partially exposed, on the road surface. I couldn't avoid them entirely and to avoid most of them I had to cut my speed way down. Between the rocks, the matrix was sometimes loose sand, a nightmare even for my lightly loaded touring bike. And by this point, the sun had warmed the atmosphere around me to the days high. The next ca. eight miles were a real struggle, physically and mentally. So much so that when I returned to what was likely the other end of the alternative left at the split, I expelled a fair amount of anxiety from my mind and body, through many controlled breaths, as my heart rate came back down to normal. On a surface that, in hindsight, was better suited for a mountain bike, the safety of my touring bike was a big concern over the ca. 8 miles of rough road especially this early in my ambitious tour. Concerns withstanding, days later I discover that I had actually done some damage to the bike, details in a forthcoming blog. Unaware at the time, in blissful ignorance, shortly after exiting the 'river bed trail' I picked-up my pace and enjoyed the ease of a hard-packed dirt road all the way to the junction with Route 1 including, between, a few miles on South Princeton Road, also quality dirt. In total, once I negotiated the eroded transition from dirt to asphalt, about a two foot vertical drop, 63 miles of mixed surface, dirt (aka, gravel) roads were behind me from where I had rolled onto the gravel in Milford earlier in the day. From South Princeton Road, I turned right onto Route 1 towards South Princeton, Maine and then continued, after a photo, towards Calais where I had booked an AirBnB option the night before. On the outskirts of Calais, I found a desperate grocery store, more junk food than health food, but I made the best of it as I've had to do many times before. About 20 minutes after shopping, I arrived to a palatial, furnished, basement apartment at about 5:30 pm, plenty of time to eat, clean-up, check-in with Tanya back in Belgrade, and come down from a day that was filled with adventure. Stud Mill Road delivered on all of my expectations and more, including a chance encounter with a goshawk and two ruffed grouse. It was then and would remain a highlight of the tour. My advice is go there, pack light, consider using a mountain bike, and be sure to go straight (not left) at the split. Everything in life is better when you earn it, even the rests between feel better when you've dug deep, persevered, and overcome a difficult challenge. In my next blog entry, I'll pick up the story from Calais: the next morning I crossed the border, less than a mile from my bed as the crow flies, into Saint Stephen, New Brunswick and then made my way, at a fairly easy pace, to the provincial capital, Fredericton and the river that embraces it, the St. John. Tanya, my friend and host back in Belgrade, kindly offered to monitor my progress on the tour and I was grateful to have a virtual friend close-by throughout the journey. Here's an excerpt of our text messages from shortly after I resurfaced on the opposite side of Stud Mill Road, in Calais, Maine: Andre: 90 miles [from the Milford Motel], 63 miles of dirt, rocks, sand, and mix, another adventure is in the bag. Wowza, that was a lot of hours and a tough route for all the weight on my bike. But still the very best option [for crossing this part of Maine to New Brunswick, Canada], less than five vehicles. Andre: When I rolled back onto the black-top [over 6 hours after leaving Milford], I was relieved and smiling. Tanya: You made it and that's what counts and no traffic. Black top is not overrated .... where are you spending the night? Andre: In Calais, for 40$, one of the nicest Airbnbs that I've stayed in. Really nice for the cost. Andre: [Two beds], a full bath, and an outdoor patio with a view [of forested Appalachian hills and valleys]. Tanya: Nice! Andre: I've already booked into what looks like another nice Airbnb for tomorrow night, Fredericton, 36$. Tanya: Bargains galore! Andre: More like Europe than the majority of the US. Nice for a shoestring traveler with ambitious goals. Tanya: Any good food around? Andre: I stopped at a [desperate] grocery store, I'm wiped out, bought breakfast too. Tanya: Good  Light and chance are always playing with us on a long tour. When I arrived to the Penobscot River in Old Town, Maine the light was not so good, which gave me an excuse to have some fun with Snapseed, a photo editing tool, from Google. That's the Milford Dam in the center of the image. 26 August 2018. (left) Navigating my smart phone for a photo somewhere on Stud Mill Road, my Garmin eTrex 20 GPS and Garmin 520 are attached to my stem and handlebar, respectively; (right) The welcome sign in South Princeton, apparently the home of Moses Bonney, my first encounter with civilization after exiting Stud Mill Road.

1/30/2020 03:34:24 am

Though I know that the journey is going to be long, I still have this feeling that I need to of there and see it for myself. I am a person who loves thrill that's why I am utmost excited to try and see it for myself. I guess, it would be very challenging to get through all these trails, but I am sure that once you reach the destination, all the sweats will be worth it. Cycling is always fun, and we all know that! Comments are closed.

|

�

André BretonAdventure Guide, Mentor, Lifestyle Coach, Consultant, Endurance Athlete Categories

All

Archives

March 2021

|

Quick Links |

© COPYRIGHT 2021. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed