|

Wondering why my blog seems to have been abandoned by it's author? Here's the story: Weebly's Blog features are truly desperate, and I say this as a software developer with thirty years of experience in the business. A simple table of contents would be brilliant, and other helpful search and browse options easily come to mind. In the meantime, Weebly offers category (aka, keyword) and archive options, both are clumsy and far too time consuming for the average visitor. With all this and more in mind, a few years ago I transitioned to integrating all of my on-line, published writing onto standard, stand-alone, web pages in place of this blog. This is why my blog (and activity) appears dated on this page, I've actually written throughout the life of my website, you'll find examples integrated into my 2019 and 2020 bike tours. It's not impossible that I'll add another blog-entry to this page but it's certainly unlikely unless Weebly vastly improves this feature of their website platform.

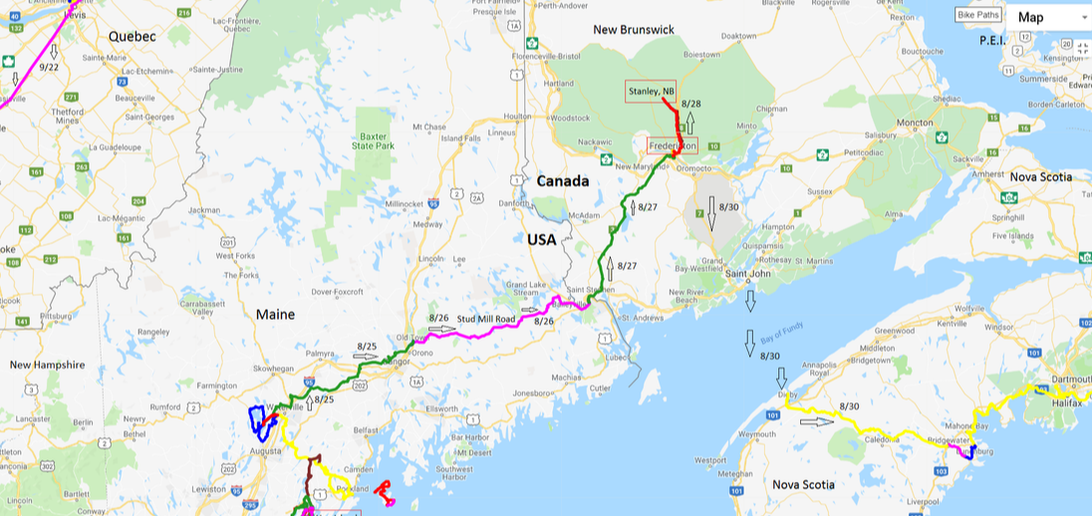

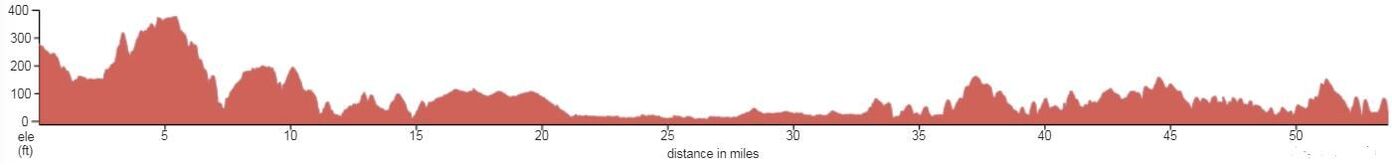

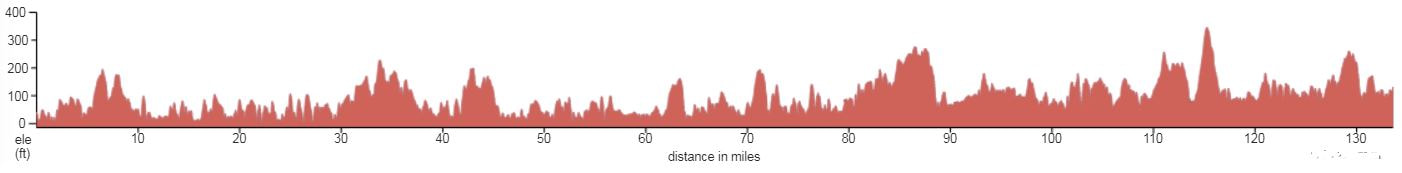

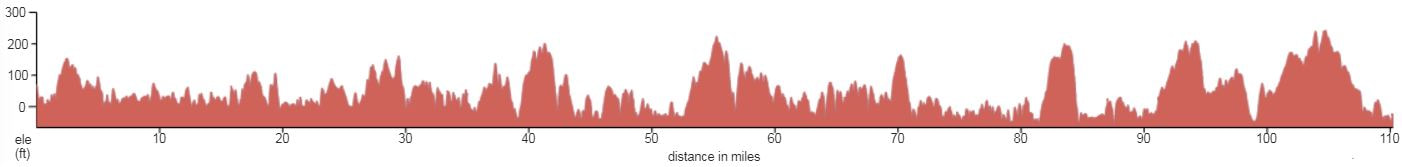

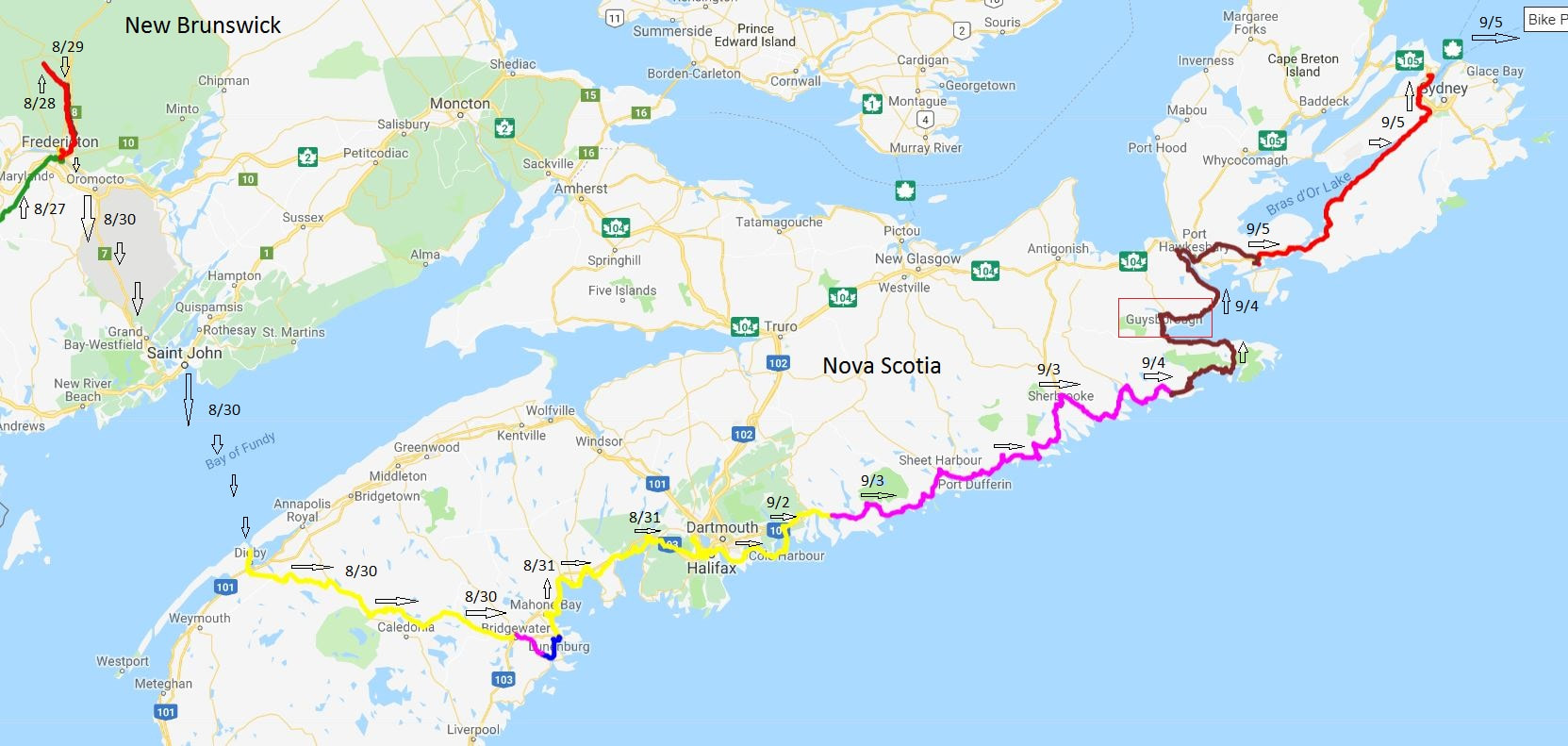

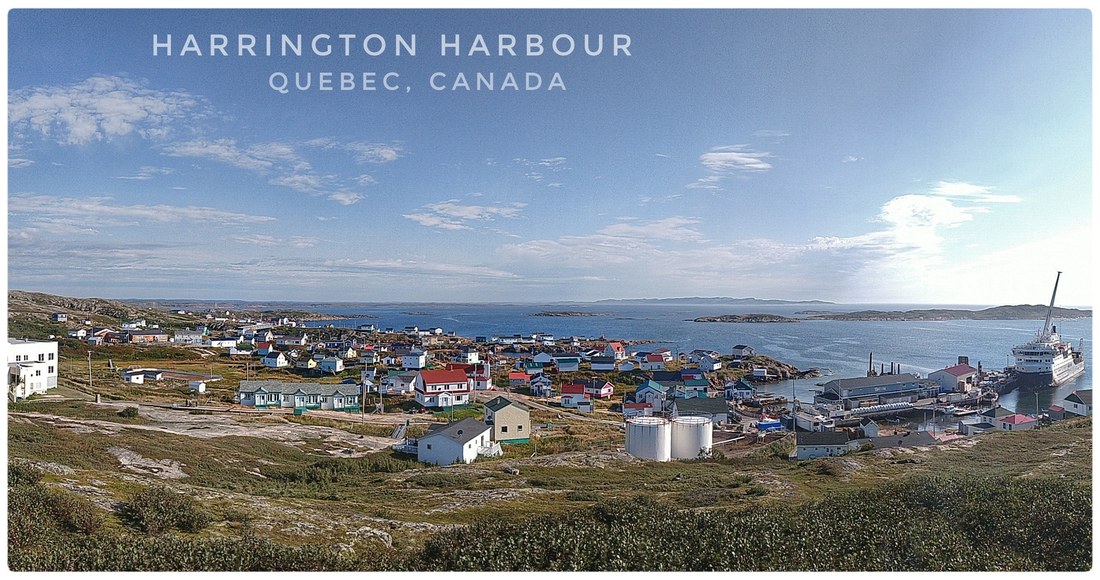

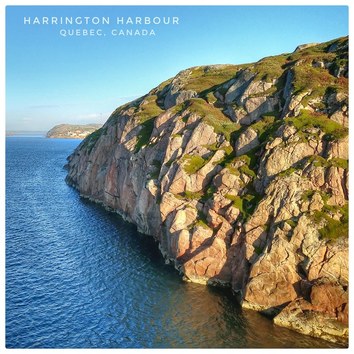

Top-to-bottom: 2 September: 53.6 miles +2569 ft / -2808 ft, Halifax to Head of Jaddore; 3 September, 133.6 miles +7,621 ft / -7,530 ft, Head of Jaddore to New Harbour; 4 September, 110.2 miles +6,918 ft / -7,014 ft, New Harbour to Louisdale; 5 September, 78.7 miles +5,271 ft / -5,246 ft, Louisdale to North Sydney, Nova Scotia. Background: This is the sixth blog entry, the first a prologue, in a series that when completed will tell the story of my 2018 autumn cycling tour through New England (United States) and eastern Canada including Newfoundland and Labrador. Please scroll down this page to read the story in the order that the events occurred starting with my arrival to Maine on 10 August 2018 described in the prologue, Going Full Tilt to Newfoundland and Labrador. Amidst the privileged comforts of Lavi and Saranyan's home in the suburbs of Halifax, I dreamed of unfriendly dogs and remote dirt tracks as Planet Earth peacefully transitioned, in the exceptional loneliness of outer space, into a position in our solar system that signaled a new month on a calendar familiar to you and I and first proposed by the Council of Trent in 1545, when Pope Gregory the XIII served as mankind's primary liaison to God. When I woke it was the 1st of September, 2018, a day closer to an impending autumn but for now the very best, at 44.65 degrees north latitude, for the outdoor pleasure of man, beast, and vegetable. Beyond the shades of my makeshift bedroom, my eyes and other senses were greeted by brilliant blue skies, sunshine, the anticipation of cool temperatures, and no detectable wind. A glorious day, a gift from the cosmos to enjoy by any means including the comfort of Saranyan's passenger vehicle and shoes made cheap by generous factory workers far, far away, where modesty no doubt remains a celebrated moral value.

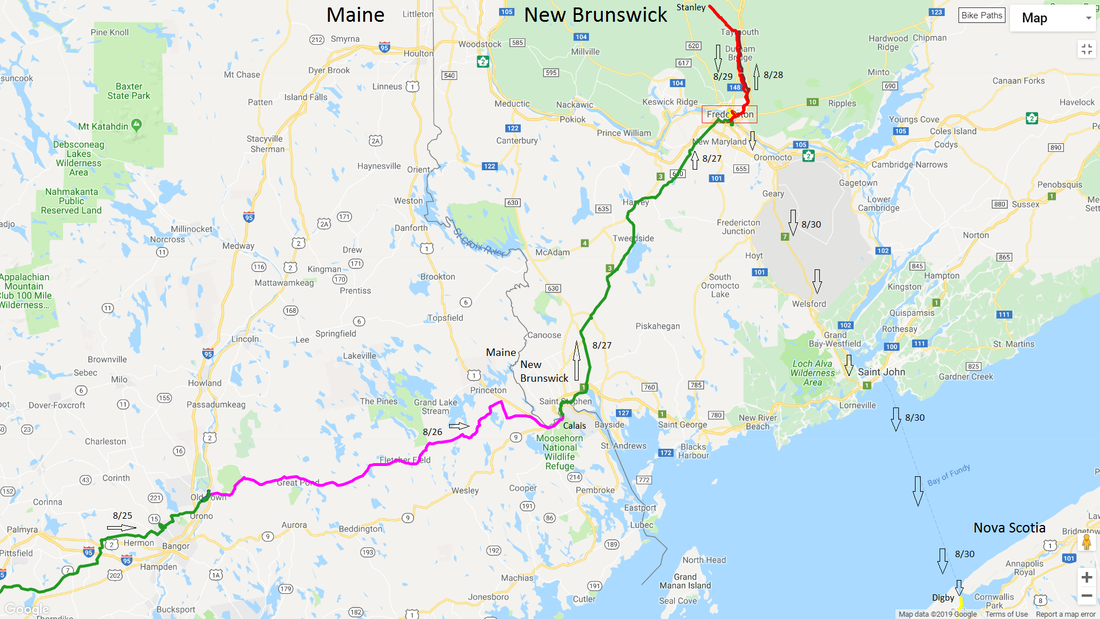

My route from Fredericton, New Brunswick (not shown on map) on 30 August to Saint Johns where I caught a ferry to Digby, Nova Scotia and then bicycled to Middle Lahave; and the next morning to Halifax, 31 August. I've included my departure routes form Halifax for perspective, my next blog entry will cover Halifax to North Sydney. Background: This is the fifth blog entry, the first a prologue, in a series that when completed will tell the story of my 2018 autumn cycling tour through New England (United States) and eastern Canada including Newfoundland and Labrador. Please scroll down this page to read the story in the order that the events occurred starting with my arrival to Maine on 10 August 2018 described in the prologue, Going Full Tilt to Newfoundland and Labrador. As much as I try to avoid commitments on my adventures, preferring instead to fly-free whenever possible, occasionally a commitment arises by design or necessity that requires me to be somewhere on a particular day, and perhaps time as well, for a rendezvous with some-one, or some-thing, such as a ferry boat. This tour had more than it's share of commitments, much more than any of my previous explorations by boot, boat, motorcycle, or bicycle. Most involved friends ...

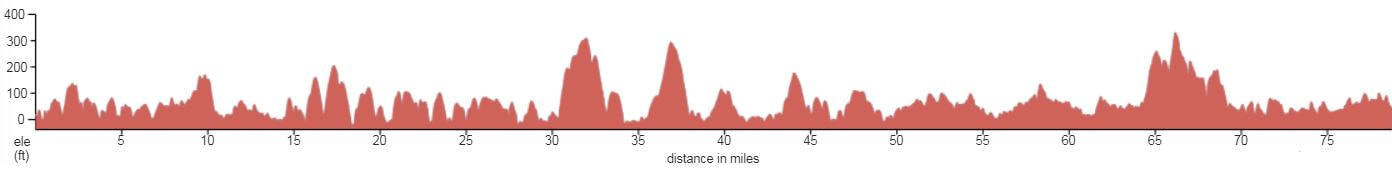

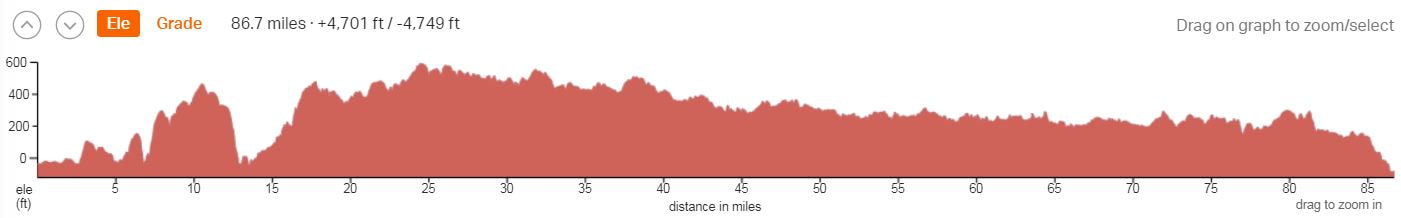

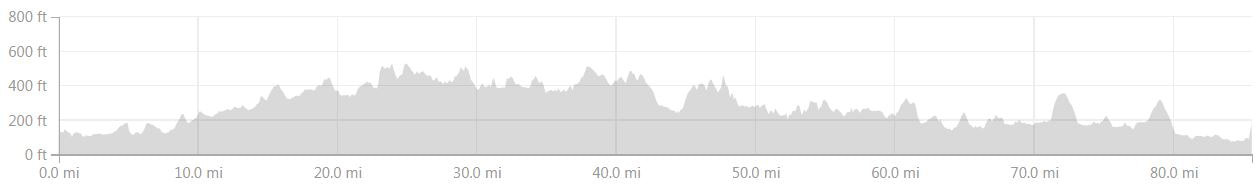

This map includes a portion of my route through Maine including Stud Mill Road (pink). The green line, center, provides a GPS impression of my route from Calais, Maine to Fredericton, New Brunswick; the elevation profile (above) is from this section. I crossed the border into Canada at Saint Stephen. The red line and nearly overlapping brown, records my route to/from Stanley from Fredericton, 27-29 August 2018. My departure route from Fredericton to Digby, by car, ferry and bike, is provided for perspective. Background: This is the fourth blog entry, the first a prologue, in a series that when completed will tell the story of my 2018 autumn cycling tour through New England (United States) and eastern Canada including Newfoundland and Labrador. Please scroll down this page to read the story in the order that the events occurred starting with my arrival to Maine on 10 August 2018 described in the prologue, Going Full Tilt to Newfoundland and Labrador. On a hill high above the St. Croix River, the border between the United States and Canada in this remote corner of Maine and New Brunswick, I stirred from my last phase of light sleep after an evening, no doubt, spent dreaming, in REM, of my adventure on Stud Mill Road the previous day ...

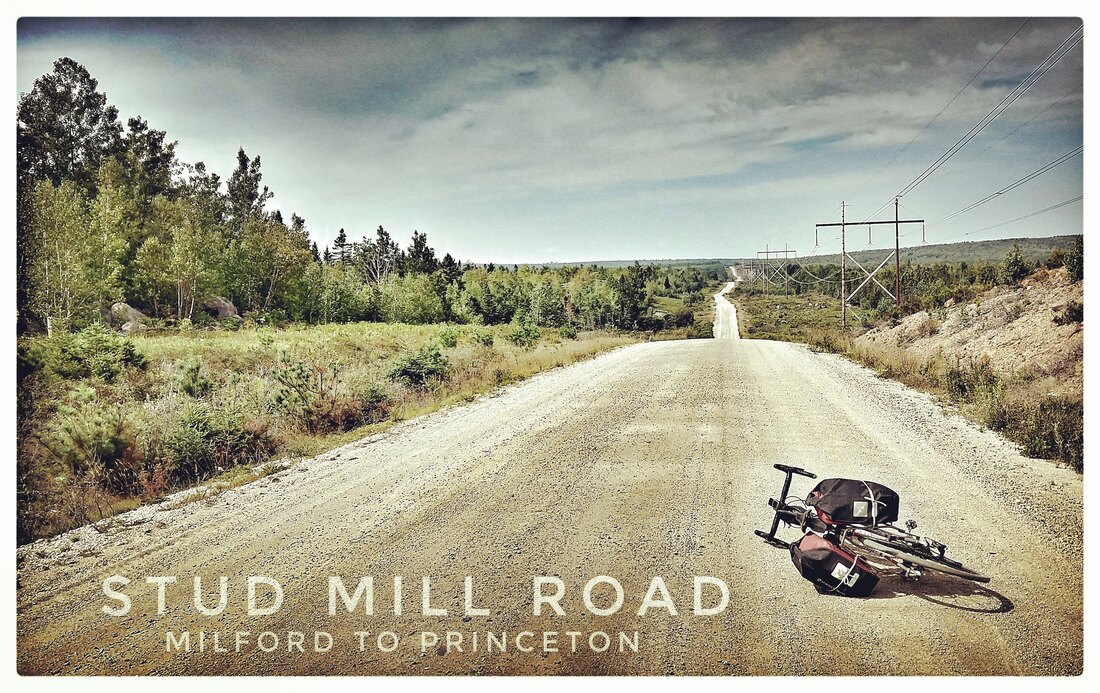

The Belgrade Lakes to Calais, Maine including sixty-three miles of gravel on Stud Mill Road.5/31/2019

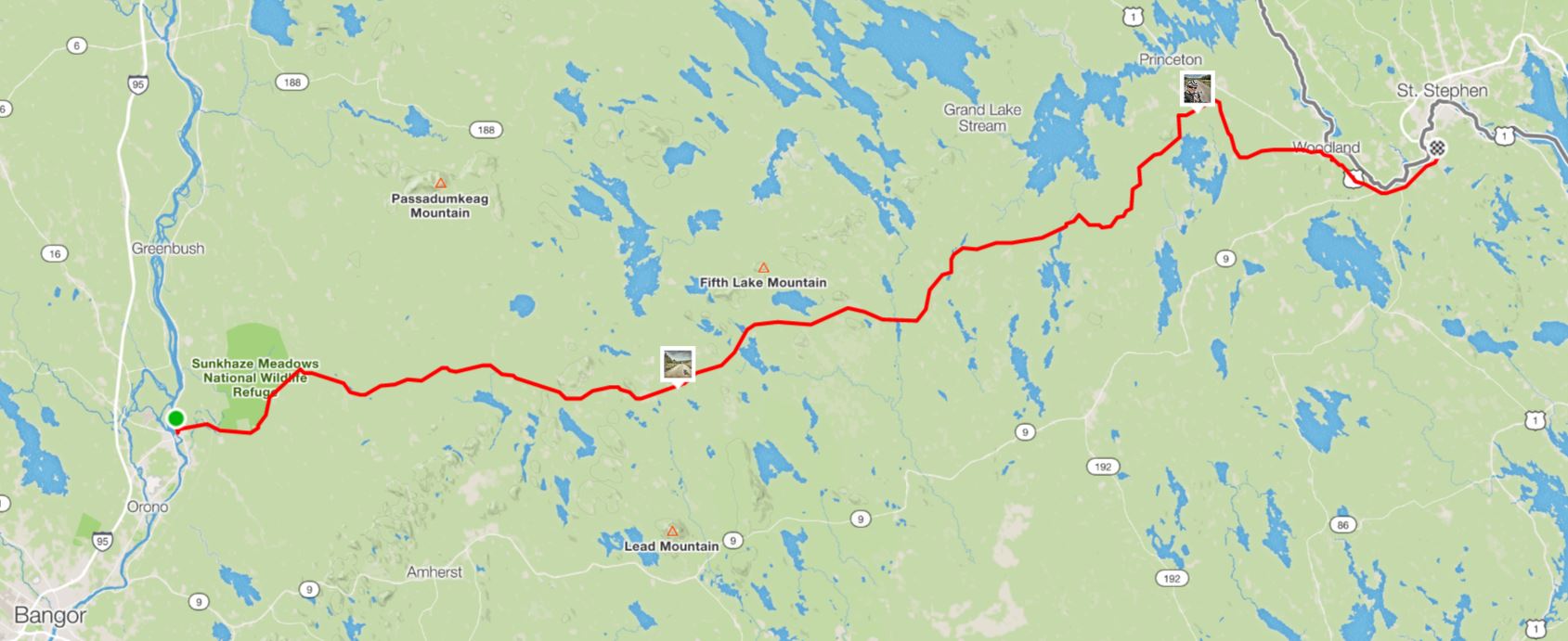

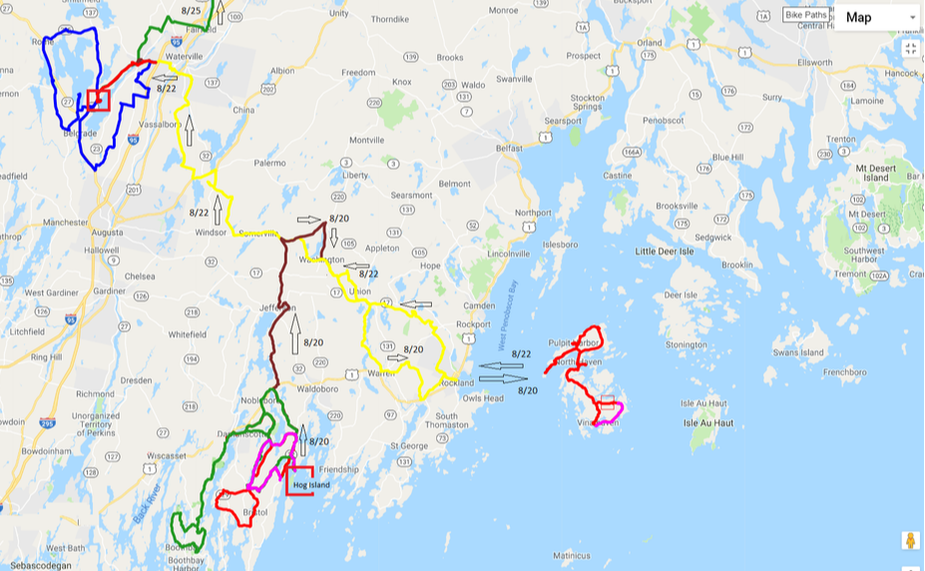

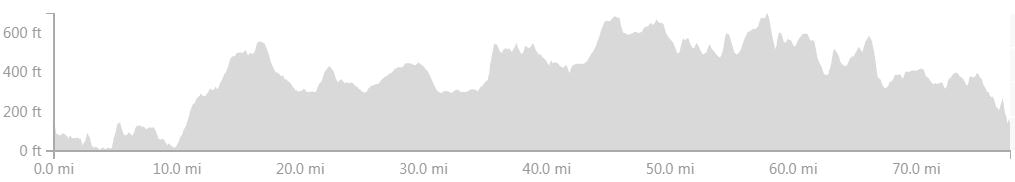

Milford to Calais, Maine, 26 August 2018. Most of the route is on Stud Mill Road (elevation profile above). The opening few miles are on County Road in Milford, the last few are on South Princeton Road (dirt) and Route 1 (asphalt) in Princeton and Calais. Note the small boxes, these are the locations where I photographed the bike lying on Stud Mill Road (left) and me with my sunglasses dipped on my nose (right), both images are included in this blog entry.  My route from the Belgrade Lakes Region to Milford (8/25), Maine, then (pink line across the middle of the image) across Stud Mill Road to Calais, Maine (8/26). When the route turns north, I'm almost immediately in New Brunswick, Canada (8/27), starting at the border in Saint Stephen then north to the provincial capital, Fredericton, and eventually (8/28) Stanley at my northern most ascent. I've also included my route from Fredericton to Nova Scotia via a ferry across the Bay of Fundy. As well as a part of my route from 9/22 through Quebec. I'll write about these bonus routes elsewhere, here they are provided only for perspective. Background: In this blog entry, I pick up the story, from my previous entry, at my departure from Messalonskee Lake in the Belgrade Lakes Region of Maine where I stayed for three nights at a friends cabin. This is the third in a series of entries, the first a prologue, that will tell the story of my autumn 2018 cycling tour through the Northeastern United States, Canada's Maritime, Newfoundland, Labrador, and Quebec provinces. I hope to finish the massive writing project before I depart on my next tour, John-O-Groat's, Scotland to Istanbul, Turkey, ca. 20 August 2019. One half of my genetic story, involving a great grandfather of French descent, the other was a Scottish immigrant that settled in Kansas, may have included the nearby town of Waterville, Maine. Henri Breton, his wife, and two children certainly immigrated from France to Canada then, within a couple of years or less, migrated to and settled somewhere in northern Maine ...

Mid-coast Maine, from Boothbay Harbor to Mount Desert Island, the foundation of Acadia National Park. Colored lines are GPS tracks from my autumn, 2018, tour including exploratory rides on and off the Pemaquid Peninsula, around the Belgrade Lakes, and on "two havens" (see text for details) in Penobscot Bay. Arrows provide direction of travel and dates the day that I completed each section. Background: This blog entry is the first of several parts, currently being written, that follow a prologue to my autumn 2018 bicycle tour. In the prologue, I provide important background info for this entry and subsequent entries. Scroll down to read the prologue which I coined Going Full Tilt to Newfoundland and Labrador.  Favorable conditions for my 20 August 2018 departure from the Nash House, Bremen Township, Maine. Favorable conditions for my 20 August 2018 departure from the Nash House, Bremen Township, Maine. From the enviable vantage of the Nash House at the end of Keene Neck Road, I sipped coffee, absorbed sunshine on the front deck overlooking the narrows, and contemplated my commitment. It was the morning of August 20th, 2018, departure day from Bremen township on the Pemaquid Peninsula, part of the middle-coastal region of Maine. What lay ahead I could not say with certainty but my experience on previous adventures suggested that there would be much to overcome over many weeks of touring by bicycle through the United States and Canada including remote areas that, despite their distance from the Arctic Circle, were Arctic in reputation and character. That reputation was of particular significance to a guy riding a bicycle, wearing ...  An enviable view from the vantage of a wee cabin many miles off the coast of Maine, August 2018. An enviable view from the vantage of a wee cabin many miles off the coast of Maine, August 2018. After my longest and most successful season of training and racing to date, I made my way from Denver International Airport, on August 10th, 2018, to a faraway island, many miles from the mainland, to Seal Island National Wildlife Refuge in Penobscot Bay, Maine, where I spent a few days with old and new friends, including many Atlantic Puffins. My idea for this autumn adventure was to reunite with old friends from my days working as an education intern (1993-1994), a seabird conservation biologist (1995-2001), and graduate student (2000-2005) in the Gulf of Maine and also to add a bit of my latest passion to the trip: some sort of bicycle tour, length and exactly where I would go to be negotiated and perhaps finalized as I sipped coffee, socialized, scanned the land and sea for birds, and otherwise decelerated ... From the third floor of a circa 1890s Victorian-style home on the corner of Elm and North Streets in Saco, Maine, on the morning of 12 October 2018, I can easily visualize the finish line of my ca. two month autumn cycling tour. To complete the cycled portion of my great circle route (see map image below), I dedicated 34 days of the tour, out of 53, to bicycling. On the remaining 19 days I mostly explored locally by bike, spent quality time with friends and family, worked, or enjoyed the perspective from the passenger seat of an 18-wheeler or a cargo ship. Average distance cycled over the 34 dedicated cycling days was about 82 miles with 4200 feet of climbing per day. Total miles cycled will likely be close to 3100, my most ambitious tour to date, when I reach Bremen later today and the dock where the tour began on August 20th. With those cycling miles came hills of most sizes totaling more than 160,000 vertical feet of climbing, equivalent to five and half times up Mount Everest from sea level. Tomorrow I arrive and soon I rest, but not for long. There is far too much to see and even more to dream during our short lives on Planet Earth.

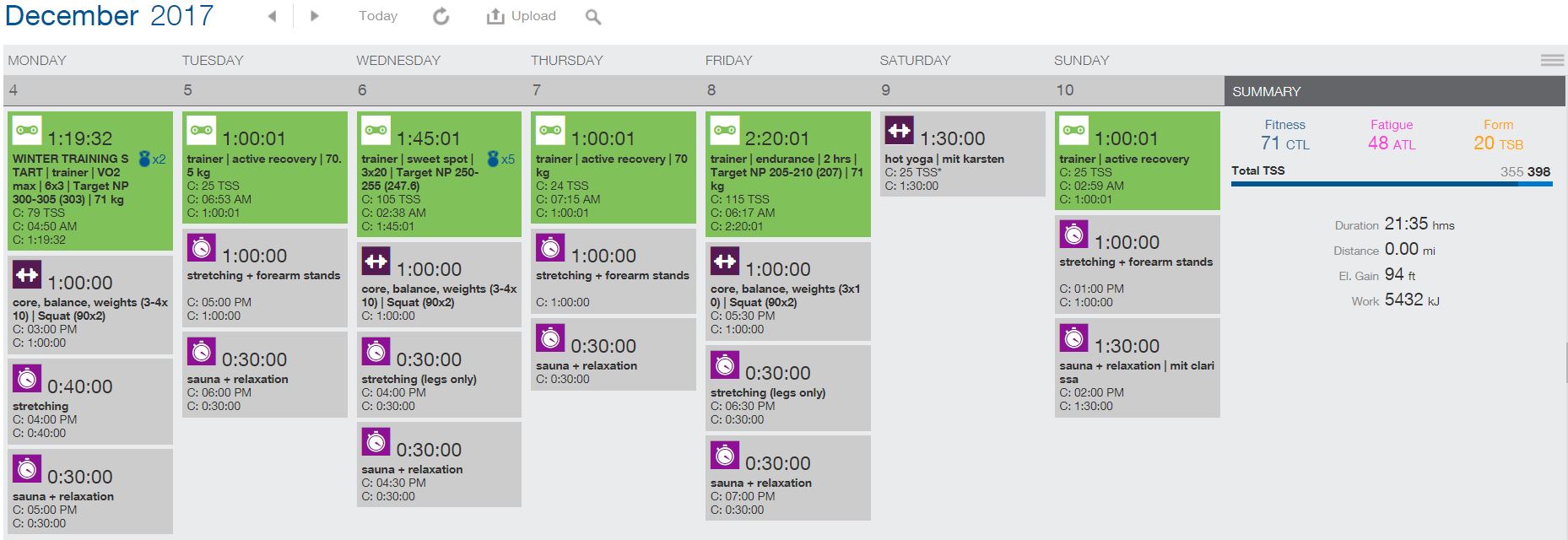

Please check back in to my blog over the next few days for a full account of my 53 day cycling tour through greater New England, USA, and Canada's Maritimes, Newfoundland, Labrador, and Quebec. Summary: Inspired by advice from a friend and pro racer, David Krimstock, and the book Training and Racing with a Power Meter, I set-out in early December 2017 to elevate my Functional Threshold Power (FTP) from where I was at the conclusion of racing in 2017, 270-280 watts, to 300 watts. I trained three components of my cardiovascular and physiological systems, endurance, sweet spot, and VO2 max, alongside an aggressive gym program involving weights, core, balance, and flexibility exercises. After nine weeks of structured, multifaceted, and intensive training I achieved or came very close to my ambitious goal, an FTP in the range of 295-300 watts. Since leaving Deutschland and entering the amatuer racing circuit in Colorado, I've had three top-of-the-podium finishes in my very competitive 40-49 age category, a first place finish overall at the Salida 720 racing as part of a pro-expert duo team, a solo fifth overall at the Bailey Hundo, and most recently a solo 7th place overall at the Breck 100. These performances were the result of planning and hard work over the winter and the kindness of others that were willing to share their experiences and knowledge of the sport of cycling. Part 1: Background, Schedule, and Dose.  October 26, the end of the last ride to reach 10,000 bicycling miles in 2018., Hamburg, Germany. Jersey from Subculture Cyclery in Salida, Colorado. October 26, the end of the last ride to reach 10,000 bicycling miles in 2018., Hamburg, Germany. Jersey from Subculture Cyclery in Salida, Colorado. Despite common sense, intuition, and logic, hard work does not guarantee improvement in sport especially as an athlete accumulates years of experience. As that experience approaches about 7-10 years, a hard working / training / recovering athlete transitions to marginal gains for the same effort that delivered much larger gains in the past. Sadly, these marginal gains may not even keep pace with losses, due to aging, illness, poor nutrition, etc, during the same period. Six years into my cycling and racing history (2013-present), at 47 y.o., aging is a significant factor nipping away, each year, at my physiological capacities. Aware of this process and how it might affect my long-term competitive goals, in December I initiated my most ambitious interval training program to date in December 2017 in prep for racing in 2018. My decision to plan and execute an ambitious winter training program in-prep for the 2018 race season began with serendipity when I shared a meal with Shimano-Pivot Cycles sponsored, professional mountain bike racer, David Krimstock, following the 2017 edition of the Fat Tire 40, part of Crested Butte Bike Week. Although I'd considered many times before, especially since I started self-coaching in 2017, integrating a more robust interval training program into my usual endurance training so far I'd failed to make that happen. For some reason, my encounter with David, a super-fast, super-friendly, and studied athlete, finally pushed-me over-the-top of whatever obstruction was holding me back from implementing a full-on, pain cave, interval program. After the Fat Tire 40, I rode-on, eventually finished my 2017 racing season with a 1st place, age 40-49 finish at the Breck 100 on 29 July and then flew to Europe where I pedaled from Hamburg to Scotland on my Niner Bikes RLT 9 Steel. From Scotland, I flew back to the United States to accommodate a month-long cycling tour of New England and adjacent states (USA) to visit friends and family. By the middle of October I was back in Europe and settled-into my winter home (at that time) in Hamburg, Germany for some much needed rest and recovery. I spent the remainder of October casually pursuing, on the nice days, my 10,000 mile year goal which I completed on October 26th. Otherwise, I spent October and November refining ideas about how I might use the winter to interval train, improve my daily nutrition, and add strength to my cycling muscles through weight lifting. By the middle of November, static, Darwinian, armchair, reflection transitioned to physical testing on the bike and in the gym where I further refined my ideas and also measured my base fitness level including Functional Threshold Power (FTP). By the end of November my confidence was high, I knew when, how much (schedule and intensity), how long, and what I hoped to gain. My structured, multifaceted, and intensive winter training program would begin on 4 December 2017, almost a month earlier than any other season to date. By the end of March 2018, I was hoping to push my FTP to 300 watts, my primary objective, through a combination of interval training on the bike, weight lifting (squats, deadlifts, and overhead presses), core, balance and flexibility training, and improvements in daily nutrition including weight loss. As December approached, I performed one 20-minute FTP test in late November, the result was 248 watts. I performed the test on the road, invariably on varying terrain, on a day I felt I wasn't rested and following a few weeks of otherwise light activity on the bike. My guess was then and remains that with fresh legs rolling on an ideal surface, no dips in the road, stop signs, etc, I could have output closer to 260 watts which is the number I used as my FTP, rather than 248, when I started training on 4 December. Before I get into the details of what transpired on and off the bike, it might be helpful to just cover the daily schedule, repeated each week, of my training program. Below, as an example, I've inserted my first week of training for the 2018 season, 4-10 December 2017, from my Training Peaks calendar. Assuming I felt rested enough on Friday to perform 2 x 60 minute endurance intervals, then my schedule would be M-W-F, all other days would be allocated to active recovery or days off. If I wasn't rested on Friday then I rested and instead trained hard on Saturday. On Mondays, typically mid-morning after putting-out any fires as far as clients / work, I'd climb onto the trainer in my office between 9 and 11 am. I warmed-up for 15 minutes then rode for 5 minutes at my functional threshold power, 260 watts, before initiating 6 x 3 minute VO2 max intervals at 105% to 120% of my FTP. If you know your FTP, then your VO2 max adaptation window is approximately 1.05 x FTP to 1.20 x FTP. For me, on 4 December, that window was 299-312 watts. By training in this adaptation window I was training and hopefully increasing the power associated with the VO2 max component of my physiological spectrum. For more details about human physiological systems and adaptation, I highly recommend Training and Racing with a Power Meter from Hunter Allen and Andrew Coggan. Outside of suggestions from David Krimstock, this book was my primary resource for planning the cycling-component of my winter training blocks. At the conclusion of the intervals, I'd climb off the bike, eat a recovery snack, towel off, change clothes, and head to the gym. The first 60-90 minutes were allocated to weight lifting, followed by core and balance exercises, then flexibility. I often concluded each trip to the gym with a 15-minute session in the sauna, or a double-dose separated by 5-10 minutes waist deep in cold water, followed by a short period of relaxation before showering and heading straight for food! It wasn't unusual for me to cash food in my locker which I visited as needed throughout the gym session. Weight lifting consisted of the squat, deadlift, and overhead press. Core and balance comprised six exercises (not always the same) done twice each, 15-50 reps. For example, I performed two push-up sets of 10-25 reps each while balanced on two yoga balls, palms-down hands on one, toes on the other. Sometimes I was tired and managed only 2 sets x 10 reps. Sometime I was more rested and crushed 2 sets x 25 reps. Flexibility involved my cycling muscles, mostly, but not exclusively. Stretching the hams, quads, glutes, and hip flexors were a priority to avoid low-back pain while walking or standing, possibly due to adaptive shortening. Although the sauna and relaxation are simple in concept I believe they are powerful in practice. Of course, there is no need to describe how to sit in the sauna and chill afterwards, but don't let the absence of details disway you. I believe heat and relaxation were important components of my winter training. Wednesday and Friday (or Saturday) were the same as Monday except for the cycling part. Wednesdays were allocated to sweet spot intervals, intervals performed at 85-95% of my FTP. The 'sweet spot' is the the part of the physiological spectrum that marathon-style mountain bike racers settle-into after their fast start and before they pick-up the pace for the last push to the finish. The sweet spot includes the well known / often discussed physiological zones known as tempo and about half of the sub-threshold zone between tempo and FTP. If you know your FTP, then your sweet spot is 0.85 x FTP to 0.95 x FTP. At the beginning of December, 2017, my sweet spot range was 221-247 watts based on an FTP of 260. My training plan allocated VO2 max to my most rested day, Monday, the day following an easy weekend. Next in difficulty and slightly less rested, I integrated sweet spot intervals on Wednesday. Lastly, on Friday or Saturday, exclusively in a fatigued state by this time, sometimes wasted, I did my best to perform two sets of 60 minute endurance intervals. The endurance zone is roughly 69-75% of FTP. At the beginning of December, I estimated my endurance zone as 180-195 watts. However, based on a lot of endurance days on the bike, and testing in November, I decided to increase this range to 200-210 watts to start. On my first endurance interval session on 8 December my goal was to maintain 205-210 watts and I was successful, some evidence, certainly not conclusive, that my intuition was correct. On Tuesdays and Thursdays I worked as many hours as possible before an easy active recovery ride on the trainer and then a shortened flexibility session followed by sauna / relaxation. I varied my active recovery rides, sometimes I maintained a cadence of 90-95 for 1-1.5 hrs. Sometimes I started and finished with 10 minutes at 90-95 rpm with 40 minutes of 105-110 rpm between. Although I don't go into the value of cadence anywhere in this blog entry, it's definitely a topic any cyclist will want to read about. I believe that training cadence is one of the primary ingredients in the recipe of any successful cyclist. The minority of successful grinders withstanding, including former pro-roadie Jan Ullrich. Saturday and Sunday, ideally, I completed an active recovery ride followed by flexibility and relaxation in the gym. Given my busy M-W-F schedule, I sometimes had to work as well, which I tried to do in the mornings. In early December, I was still planning two trips to Spain to add climbing / elevation adaptation blocks to my winter training program. I traveled to Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, from 16 Jan to 1 Feb; and later, to Mallorca from 20 Feb to 12 March. When in Spain my priority was climb, climb, climb, no gym, occasionally stretching, always eating. I took days off to work and recover. I did perform some interval sessions, including VO2 max, and FTP testing in Mallorca but those were exceptions. The rule was 'get on your bike and climb until you hate yourself'. That might sound awful but both trips provided many memorable adventures, each full of surprises with many reasons to smile and reflect. Before I flew to Gran Canaria, I completed seven VO2 max interval sessions. Because I flew on a Tuesday I completed one less sweet spot and endurance session before the first winter climbing block. Between Gran Canaria and Mallorca, back in Germany, I completed two more weeks of training on the bike and in the gym. After Mallorca, sadly by this point experiencing relationship stress that would conclude my German experiment, I added two final weeks of intensive interval training / gym sessions before flying back to Colorado on 28 March. All told, twelve VO2 max training sessions and eleven sweet spot and endurance interval sets. Weight lifting sessions were three-times per week when I was in Hamburg, so about 30 sessions involving a barbell, same number applies to core and balance. When I returned to Colorado I replaced gym and core work with many forms of hot yoga (Midline Yoga) and indoor soccer (Arena Sports) as I increased my cycling hours and waited for my body to adapt to elevation in prep for racing. All cycling was performed on my 2015 Giant TCR Advanced road bike attached to my Omnium Trainer from Feedback Sports, an exceptional, travel-friendly, unit. Thanks to a friend, I have a Quarq power meter attached to my road bike. Weight-lifting, core, and flexibility exercises were completed in the Kaifu Lodge, a short walk from my office and winter home (at that time) in Hamburg, Germany. What I just wrote covers schedule, structure, and logistics, now I'll describe the dose that I chose for cycling and weights and my overall goal / objective for my winter training program. On the bike my plan was to increase intensity by five watts each session (dose) relative to the one before. So if my VO2 max goal was 300-305 during a given week then the goal a week later, assuming I was successful, for VO2 max would be 305-310. I applied a similar strategy to my weight lifting schedule / plan, add five pounds each day (dose) to all of my sets and reps. So if I performed 3 sets of squats by 5 reps at 220 lbs on Monday, and was successful, then on Wednesday I repeated 3 sets by 5 reps (3 x 5) with 225 lbs. My hope was that by increasing power and weight incrementally over many weeks I could gradually and successfully increase my FTP to 300 watts, this was my overall goal. My decision to simultaneously (same week) train three components of my physiological system was motivated by two conclusions: 1) I'd spend less time on the trainer versus training long endurance hours for weeks, then sweet spot, then VO2 max; and 2) adaptation within each system (more power) might, sensibly I thought, cause a shift overall in my power through simultaneous adaptation. I would, I hoped, pull myself up into a stronger, faster, higher performing self by executing a winter training program that simultaneously integrated four structured training components, each imposing adaptations on different part of my body, three motivated by the bike and one by a barbell. To these physical challenges I added plenty of healthy food, active recovery, heat adaptation in the sauna, and relaxation to help motivate adaptation on the off days. This final component, a multifaceted recovery strategy, was motivated by the following reality: adaptation occurs during recovery not training. Part 2: Details Training on the Bike Day one, 4 December 2017, 6 sets x 3 minute VO2 max intervals (3-minute recovery between), followed by weights and core exercise in the gym, then stretching, then thirty minutes for sauna and relaxation. My average normalized power (NP) goal for this first set of VO2 max intervals was 300 watts, slightly above the middle of the target range suggested by David and the book by Allen and Coggan: 260 x 1.05 to 260 x 1.20 = 273-312 watts. Apparently I was showing myself no mercy on day one of my winter training program and I wasn't disappointed, I was able to maintain, despite the high-level of mental and physical suffering I experienced during all of my VO2 max intervals, an average of 303 watts (avg NP) over the six intervals: 296; 303; 306; 307; 304; 303. I went a little under my goal on the first interval, the next five were a smidge above 300 watts. Here's what I wrote in the comments section of this workout shortly after climbing off the trainer: "I'm very close to being able to sustain 310-315 for these 6x3 min intervals, closer to 300-305 at the moment but that's a big leap relative to power when I climbed onto the omnium [trainer] about two weeks ago. My body is adapting quickly, road and trainer power are equalizing though not yet equal. I'm very satisfied with today's result and looking forward to the next 6x3 session so that I can assess how much closer I am to road power." Regarding "equalizing", recall I was testing ideas in November. During this time I was also spending time on the trainer so that my road and trainer FTP would be more, rather than less, aligned, simplifying the arithmetic especially when I flew to the Canary Islands in a few weeks, then later Mallorca, where I would train almost exclusively outdoors and at intensities dictated by my functional threshold power. It's not unusual for a riders trainer FTP to be 10-30 watts lower than their road FTP but the difference tends to get smaller, or even go away, following many hours of adaptation on the trainer. Here's the complete set of average normalized power numbers for each interval from the month of December, Weeks 1-4: December 4-25, 2018 (1) 296; 303; 306; 307; 304; 303; avg 303. (2) 317; 319; 315; 310; 308; 300; avg 311.5. (3) 316; 320; 321; 320; 315; 315; avg 317.8. (4) 326; 328; 326; 327; 323; 320; avg 325. Recall that each week I increased my average NP wattage goal by 5 watts. Week one my goal was 300-305. I actually added 10 watts, not 5, to this range the second week to arrive at 310-315 based on what I felt I could do and the less-than-ideal conditions of my last FTP test. Weeks three and four I increased my wattage goals to 315-320 and 320-325, respectively. A fine detail but one worth stating here, for my trainer profile on my Garmin 520 I integrated lap normalized power as a prominent part of the display. I used this as a "carrot" as suggested by Allen and Coggan, to push myself to maintain, reach for, the planned / targeted wattage range on each interval. I can't understate the value of using this "carrot" trick to reach your goals on the trainer, especially those that involve a lot of physical and mental stress. The same trick is useful on the road and trail. Each week in December I successfully achieved my VO2 max goals, increasing by five watts per week. After a New Year celebration and before I flew to the Canary Islands for my first winter block of climbing I performed three more VO2 max interval sessions in January, Weeks 5-7: January 1-15, 2018 (5) 332; 331; 333; 330; 327; 325; 329.7 avg. (6) 337; 337; 337; 336; 335; 330; avg 335.3. (7) 340; 341; 337; DNF. As you can see, the VO2 max trainer session during week seven concluded with my first DNF, I was unable to finish interval four within the estimated adaptation range, 105-120%. After the session I wrote, "Wasn't rested, should have listened to my inner voice and not started." Maybe I wasn't rested, recall everything else, physical, I was performing each week including difficult sweet spot intervals (85-95% of FTP) each Wednesday. Of course, it's always important to listen to your inner voice, that's the 80-90% of your brain that sends brief messages to your conscious 10-20% but otherwise silently works on crunching numbers, reflecting, and much more. However, what I failed to realize on 15 January, when I blew-up during interval four, was that I hadn't failed. Instead, I'd ridden myself, incrementally, week after week, into a direct collision with my trained-state FTP, likely something very close to where I was before I stopped training in 2017. Looking back to week six, I was successful, I finished all of my intervals in the prescribed zone. If I take the average of the six intervals from that week, 335, then a rough estimate of my FTP during that session is 1.2/335 = 279 watts. Based on my 2017 power data (all files), my FTP was likely about 270-280 watts at the end of racing in 2017. The FTP estimate from session six, 279, is in that range. It seems logical that during week six I'd trained myself back to my trained-state FTP at the conclusion of 2017 racing. Any cyclist that is interested in FTP and other thresholds has not doubt complained that FTP "is just a number", or something similar, a useful reference but not "real" in the strict sense of a threshold. Before this winter I would have quickly agreed, but now I totally disagree. There is definitely something very real about the physiological threshold known as FTP. Whether yours or mine is 290 or 291 or 289 certainly isn't important. But the "line" is a real boundary, that moves around depending on our level of fitness and fatigue. Weeks later when I realized what truly happened during week seven of my VO2 max interval training it was a moment of clarity that I doubt I'll ever forget. The realization, the moment I figured it out, will always be special and it's definitely added significantly to my experience as an athlete. By incrementing by five watts per week I incrementally approached a critical component of the human physiological system and all of the processes and chemistry that this system is composed of, our Functional Threshold Power. From January 16th to February 3rd, I moved my base-camp to Gran Canaria, the largest of the Canary Islands. This was a nice break from chilly, grey, wet Hamburg. When I returned to Hamburg, I resumed my interval and gym sessions for two more weeks, Weeks 8-9: February 5-12, 2018 (8) 345; 345; 346; 342; 334; DNF. (Goal 345) (9) 345; 345; 345; 341; 328; 319; avg 337. (Goal 345) By week seven, in January, my goal was 340-345 watts per interval. Recall that I did not finish (DNFed) the fourth interval of that training session because I couldn't maintain wattage in the adaptation window for training the VO2 max part of my physiological spectrum. Subsequently, the next day in fact, I flew to Gran Canaria where I climbed a total of 58,963 feet over 459 miles on the road bike. I was sick, unable to ride, on three days, airport gunk. I took a few additional days off to rest. Total days on the bike were eight. Surviving so much climbing in such a short time gave me confidence, once back in Hamburg, to up my VO2 max wattage goal for week eight to 345-350 despite the DNF at 340-345 a few weeks before. As you can see from the numbers (above), I had some success, holding 345 watts on the first three intervals, both weeks, and completing the set of six during week nine. I was getting stronger, the ninth week compared to weeks 1-8 were proof of that accomplishment. For what remained of my structured interval training, a few sessions in Mallorca and about two weeks in March before returning to Colorado, I was never able to repeat the numbers, on the trainer, that I put out during session nine. Part of the reason was so much travel during which time my body became less adapted to the trainer. Another part was relationship stress. Nonetheless, as you'll see at the conclusion of this blog and in the next paragraph, all of the VO2 max work that I'd done up to / including my success during week nine was making me stronger. By early March I was riding outdoors under Mallorca sunshine with no excuses to postpone my first FTP test of 2018. I performed a 60 minute individual time trial on a climb that was a few minutes shy of ideal, a big dip downhill before climbing again with smaller dips before and after. Despite the terrain, I averaged 289 watts NP. At minute forty, I was holding 301 watts, right before the biggest downhill section. I don't know because I didn't do any serious testing last summer but I suspect 289 was a personal record. On March 6th, just two days after the first test, I repeated the test on the same section of road, same dips, etc, but this time held an average 292 watts even carrying the fatigue of the test from two days before. Back in Hamburg, on 27 March, I performed one more test, a 20-minute time trial. After subtracting 5%, that test suggested my FTP was 294 watts. Not bad, especially given that I had to negotiate one stop sign during the test. This test suggests that when I departed Northern Germany for Colorado I was confidently, given stop signs, etc, capable of 295 watts for 60 minutes, and perhaps even 300 under ideal conditions. Although issues of adaptation had kept me from pushing higher VO2 max wattages on the trainer I'd nonetheless achieved, or nearly so, my FTP goal at least at elevations I encountered in Hamburg and Mallorca through intensive interval training over roughly four months (Dec-Mar). Success and failure as just described for my VO2 max sessions over nine weeks was essentially replicated, for the same reasons described above, during my sweet spot, 3x20 minute intervals at 85-95% of FTP performed on Wednesdays. Here's the numbers from the first six weeks of my sweet spot training, Weeks 1-6: Dec 6 2017 to Jan 10 2018 (1) 252; 246; 245; avg 247.7. (2) 258; 252; 250; avg 253.4. (3) 261; 252; DNF; avg 255.5. (4) 260; 259; 256; avg 258.3. (5) 264; 264; 261; avg 263. (6) 270; 269; 267 (15 min); avg 268.6. Week one, 6 December 2018, I set my first goal at 250-255 watts. Recall I increased this by five watts each week, thus my goal for week two was 255-260 watts. By week six, I was hoping to stay within 270-275 watts for each 20-minute interval. Notice on week six I faltered (blew-up) 15 minutes into interval three. As I had with VO2 max intervals, I was running into my very real FTP six weeks into my sweet spot interval training. Here's the two weeks between the Canary Islands and Mallorca (back in Hamburg), Weeks 7-9: February 7-14, 2018 (7) 270; 269; 270; avg 270. (8) 275; 270 (17 min; DNF); DNS. My success during week seven was perhaps my very best on the trainer for the sweet spot up to that time. That day I had reverted to the week six goal, 270-275 watts, giving myself a slight advantage to succeed given I'd been off the trainer for weeks riding outdoors on Gran Canaria. The next week I reached for 275-280 watts and blew-up after 17 minutes during the second interval. I never started the third. It's very likely that I was above 120% of my FTP at 275 watts at least on the trainer at that time. My experience performing the much less intensive, relative to VO2 max and sweet spot intervals, 2x60 minute endurance intervals also hit a wall, I began to blow up, during week eight. Here's the first eight weeks, all on the trainer, before my endurance interval training was set-aside during my trip Mallorca, Weeks 1-7: Dec 8 2017 to 12 Jan 2018 (1) 207; 208; avg 207.5. (2) 219; 221; avg 220. (3) 226; 226; avg 226. (4) 231; 232; avg 231.5. (5) 235; 237; avg 236. (6) 241; 240 (40 min); avg 240.5. [Off the Trainer: 16 Jan to 1 Feb, Gran Canaria] (7) 240; 240; avg 240. (8) DNF; DNS. My goal during week one, 8 December 2017, was 200-205 watts for each 60 minute endurance interval. By week six (no trips to Spain just yet) my goal was up to 240-245 watts and I was able to meet that goal, 240.5 watts average over the two intervals. When I returned to Hamburg from Gran Canaria I again, as with my post-Gran Canaria goals for VO2 max and sweet spot, gave myself a slight break by maintaining the goal from week six and was successful, 240 watt average over the two intervals. In contrast to week seven, week eight was a near complete loss. And this was in part because by this time I was single but still living with my former girlfriend in Germany. Relationship stress was very high. Another factor was loss of trainer adaptation. After Mallorca, I never regained the trainer fitness I had during week seven. Part 3: Details Weight Training in the Gym For the readers convenience, I'll start this section by repeating some of what I wrote in the introduction including the basic structure of the weight lifting component of my gym exercises, the squat, deadlift, and overhead press. These were entirely new to my athletic sphere when I started planning in November 2017. I've been performing core, balance, and flexibility exercises since April 2011 and many of these exercises as prescribed by my physical therapist, Dr. John Kummrow (Integrative Physiotherapy), instructors teaching at Midline Yoga (previously at Elan Yoga & Fitness), and massage therapists including Katie Hines. As part of my 2017-2018 winter training, I continued to do these though in different reps and sets to accommodate my goals involving weight lifting. For the remainder of this section I'll write almost exclusively about weight lifting. For questions about any part of this blog entry, including core, balance, and flexibility training, I'd be thrilled to hear from you via a comment or email. The simplest way to replicate my weight lifting schedule and dose for the squat, deadlift and overhead press is to buy the book Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training by Mark Rippetoe. In it he advises a five pound weight increase for beginners per session, 2-3 sessions a week, in the gym. I played-around with weights, reps, and sets, and worked on form, throughout November in prep for December. Mark Rippetoe is also featured in many videos that are available on YouTube, such as this one. They're all excellent, informative and entertaining. Throughout, planning and implementation, I was also coached by my older brother, an accomplished weight lifter and stone mason extraordinaire. I sent him videos and he coached me on form as best he could from a distance. He answered dozens of questions. He was also my inspiration and source of courage to get under the barbell for the first time since I was a teenager. What I discovered, once I went under and over the bar, was I really enjoyed these exercises. Especially the squat. On Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, overlapping with the trainer component of my winter training program, I went to the gym and performed first weights, then core and balance, then flexibility exercises. After these workouts, which I always performed after cycling, I often collapsed in the sauna to relax and wind down. It wasn't unusual for me to spend four hours in the gym. On days I had to be quick I could shorten to 2.5-3 hours by cutting-out some of the peripheral activities and being all business. I focused on work in the early mornings and on rest days: Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday-Sunday. I was late getting Rip's book shipped to Germany so didn't actually integrate his structure, sets and reps, until 20 December. On that day my heavy set for squat was 65 kilograms plus the 20 kg barbell, 187 pounds. I performed many warm-up sets, as prescribed (exactly) by Rip, then performed 3 sets of 5 reps at 187 pounds. Based on Rip's suggestions, two days later I added five pounds to my heavy sets, 192 pounds. The hardest barbell exercise I performed was by far the overhead press, I started at a modest 77 lbs, my heavy sets were 3 x 5 reps just like the squat. I enjoyed the deadlift almost as much as the squat. On 20 December I started my deadlifts with a heavy set of 5 reps at 176 lbs, weights + bar. My heavy set for deadlifts, as prescribed by Rip for beginners, was 1 set of 5 reps. Rip predicted that my deadlift heavy weight would eventually overtake my squat heavy weight. He was right, and that occured on the 5th of February, 2018, when I successfully squatted 220 lbs (3 sets x 5 reps each) and then subsequently deadlifted 232 lbs (1 set x 5 reps). I lost and gained on all of these barbell exercises as I traveled between Germany and Spain (no gym, only cycling). On my last trip to the Kaifu Lodge, where I performed all of my gym training, I was up to the following weights on my heavy sets: squat 221 lbs, press 94 lbs, deadlift 254 lbs. I ran into marginal gains, no longer five pounds per session, about eight weeks in with both the squat and press. I continued to gain with few exceptions with the deadlift. My first three month excursion into the weight room in about 30 yrs delivered significant strength gains. For example, my deadlift increased from 176 pounds, a set of 5 reps, to 254 pounds, a difference of 78 very real pounds. I'm already looking forward to getting back into the gym in about December 2018, based in part on how much I enjoyed my time under and over the barbell last winter but also because I know that the weight training contributed significantly to my accomplishments (so far) racing a mountain bike in 2018. Part 4: Conclusion Armed with great advice from a friend and pro racer, David Krimstock, and the book Training and Racing with a Power Meter, I set-out in early December 2017 to elevate my FTP from where I was at the conclusion of racing in 2017, 270-280 watts, to 300 watts. I simultaneously trained three components of my cardiovascular and physiological systems, endurance, sweet spot, and VO2 max, alongside an aggressive gym program involving weights, core, balance, and flexibility exercises. After nine weeks of intensive interval training interspersed with two climbing blocks in Spain and the work in the gym, I achieved or came very close to my ambitious goal, at least at sea level, an FTP in the range of 295-300 watts. Given my limited experience with the sport of cycling, I suspect that what I did on the bike and in the gym was not the very best way to increase my FTP. I'll be thinking about how to make improvements and then implementing those changes in the winter of 2018-2019. But those forecasted improvements aside, it turns out my 2017-2018 plan was effective without requiring excessive hours on the trainer and I learned much more than I anticipated along the way, a nice bonus. Since leaving Deutschland and entering the amatuer racing circuit in Colorado I've had three top-of-the-podium finishes in my very competitive 40-49 age category, a first place finish overall at the Salida 720 racing as part of a pro-expert duo team, a solo fifth overall at the Bailey Hundo, and most recently a solo 7th place overall at the Breck 100. A few weeks ago when I climbed off the bike in Bailey, Colorado I knew I'd accomplished something very special for my modest, endurance-distance, racing palmeres, a breakthrough performance that was made possible by planning and hard work over the winter and the kindness of others that were willing to share their experiences and knowledge of the sport of cycling. Please check back in to Andre Breton Racing Dot Com for future blogs dedicated to my winter base camps in Gran Canaria and Mallorca among other topics from my 2018 training and racing experiences.

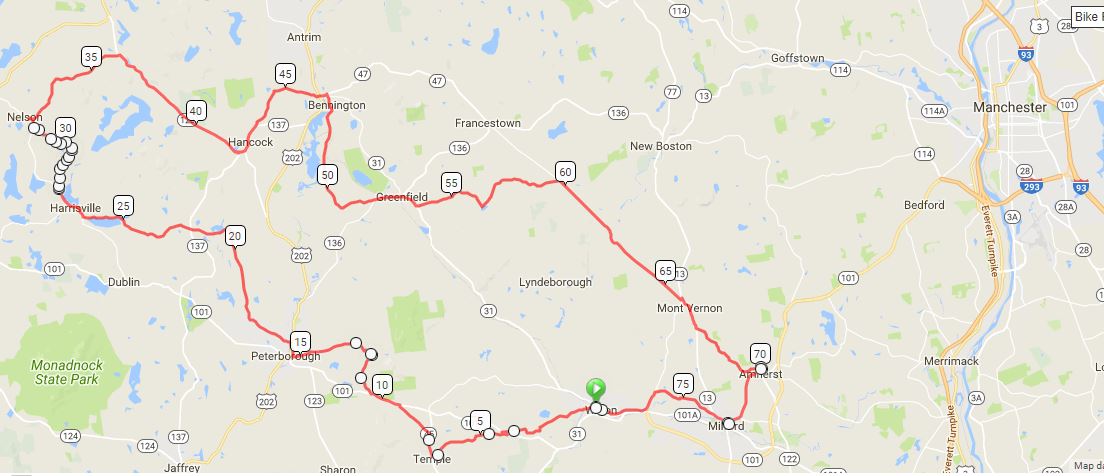

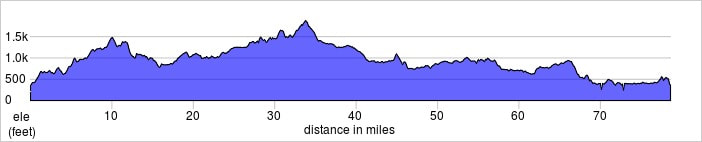

Tour of New England and New York, 9/5-10/8/2017. Tour of New England and New York, 9/5-10/8/2017. Summary: This blog entry is the first of three intended to capture my impressions, and more, from a cycling tour of New England and New York that I completed from 9/5 to 10/8/2017 amidst lots of days off the bike to spend quality time with friends and family. My primary goal for this three-part impressions series is to inspire others to explore the regions rural routes, quaint villages, and scenic landscapes by bicycle. In this entry, I recall impressions from a day of cycling through eleven historic villages in southern New Hampshire's picturesque hill country starting and ending at the Sky Bridge Cafe in downtown Wilton. The entry is written as if you, the reader, are following my route on a bicycle and I'm a voice in your head providing directions along the way including suggestions for satisfying your inevitable food and caffeine cravings. I've also inserted a touch of history as it relates to the land and the villages on the route. From Wilton and the Sky Bridge, my eleven-village tour proceeds west, clockwise (see map below), first to Temple then Peterborough, Harrisville, Nelson, Hancock, Bennington, Greenfield, Mont Vernon, Amherst, Milford, and ultimately back to Wilton and the Sky Bridge. With the exception of Peterborough and Milford, both "towns" by any measure legal or otherwise, the word "village" provides an appropriate visual cue for the other nine. Within the villages and the much larger town centers of Peterborough and Milford are some wonderful opportunities for the curious food and caffeine motivated traveler. Among them the Sky Bridge Cafe of course, but also the English-inspired Birchwood Inn and London Tavern in Temple, the Harrisville General Store, the Local Share by Plowshare Farm in Wilton, and the Union Coffee Company in Milford. Between the villages you'll find a bit of Alice's Wonderland, a patchwork landscape of hills, forests, and farmlands. I hope my blog entry will inspire you to explore, by bicycle, this relatively undiscovered region in New Hampshire. If you can't make the trip on a bicycle then carpool with a group of lucky friends and family! Before delving into the ride, my impressions, and more, let me start-out with some details that will be helpful for anyone wanting to repeat this ride as I completed it, all eleven villages in a day including stops for photos, snacks, drip coffee (Harrisville General Store) and a latte (Union Coffee Company, Milford). In this opening section, I'll include details about road surfaces you'll find on the route and some tips to keep in mind including tire pressure and bike choice for maximizing the fun factor on dirt with minimal loss of efficiency on pavement. The route, including out-n-backs for coffee and town-center visits, is 78 miles (126 km). Along the way, you can expect to climb, according to Strava, about 5850 feet (1783 meters). My time on the saddle, moving time, was five hours two minutes. Elapsed time, including two stops for food and coffee, was six hours thirty-four minutes. Here's a link to the route on Strava where I go by the alias Lava Monkey. I used Ride With GPS to assemble and save my route in a format (GPX file) that could be read by my Garmin eTrex20 GPS device. Turns along the way were informed by previous rides I've done in the area. I favored roads-less-traveled and avoided, whenever possible, state-maintained "highways" such as the 101 and 31. As their designation implies, these routes are the primary corridor for high-speed traffic including freight. I'd advise staying off of them especially the noisy, busy 101, an alternative route connecting Milford, Wilton, and Peterborough. Among the roads-less-traveled, I favored paved routes mostly, but not exclusively, for this tour because I knew I would be advertising and recommending the ride to a wide-readership on my blog. On other rides I've done through southern New Hampshire's hill country (see links at the end of the blog), I favored a higher percentage of mixed-surfaces including dirt roads and rail trails (bike paths built on former rail beds). My eleven village tour is close to 90% paved vs. non-paved, so I'd advise tire pressures that favor paved roads with only modest softening for the few dirt roads that you'll encounter. With the proper bike, "dirt" roads, sometimes referred to as "gravel" roads, a highly varied road surface, can add immensely to a cycle tour. With modern "hybrid", alternatively "gravel", bikes and the features they offer, such as tubeless tires and steel frames, these surfaces can be ridden safely and comfortably at much higher speeds than a road bike with 90-120 psi tire pressures front and rear. When preparing my Niner RLT 9 Steel gravel bike (50-36 rings, 32-11 cassette), the bike I used on this ride, for non-paved surface such as gravel roads, cobble stone, and non-technical single track, I inflate my tubeless Hutchinson Sector 28 mm tires to 85 psi rear / 75-80 psi front. Over a calendar year, my body weight varies from about 150 (race fit) to 160 (off-season) pounds (68-72 kg). You'll want to factor in your own body weight when softening your tires. Too low and you could easily damage your rim or pinch a tube if you're not rolling tubeless. There is also the trade-off to keep in mind between decreasing efficiency on the paved roads with gains, as you drop tire pressure, in efficiency and safety on the mixed-surfaces. Unless you know a garage code in Wilton or another town nearby, where you can bunk for the night as I did, then you'll likely drive into Wilton center with your bike on a rack. You'll find ample parking in the town center. Given that you'll be gone most of the day I advise parking off the main street. The Sky Bridge Cafe is close to the west edge of downtown, a short spin from any parking option. Depending on which day and time you decide to set-out on this tour of eleven villages, or any other ride that starts in Wilton (see suggestions below for more routes), you may find that the Sky Bridge is either closed or not yet open the morning that you arrive. An excellent alternative is the Local Share by Plowshare Farm, quality drip coffee and espresso, organic baked goods, locally made art, and even local produce when in season. To find the Local Share cross the street from Sky Bridge and take a left, a few doors down, across from the historically significant and locally celebrated Wilton Town Hall Theater, you'll find the Local Share. If you drove in then you likely arrived off the 101 from Milford. On your way, you may have noticed that the roads were essentially flat as you made your way from interstates to the 101 eventually to Milford and then Wilton. You were driving across a former, mostly flat, outwash plain comprised of sands and gravels left behind by receding glaciers, ca. 11,000 years ago (from the most recent cold period of the ongoing Quaternary Glaciation) Alternatively, if you came from the west on the 101 then you came through hills associated with the extensive and geologically ancient Appalachian Mountains, a landscape feature easily seen from space whose origins date back ca. 480 million years to the so-called Age of the Fishes, well before the evolution of reptiles and mammals. From Peterborough heading east towards Wilton, the 101 climbs up-and-over a section of Temple Mountain (2,045 ft (623 m)). Like all of the hills in the region, the bedrock of Temple Mountain is mostly metamorphosed schist and shale, rock layers that record the former existence of a sea of an antiquity even older than the Appalachians. As this overview of the geography of southern New Hampshire implies, from Wilton heading north, towards Greenfield, west back towards Peterborough and Keene, or south towards the village of Temple you can expect to encounter a region dominated by hills and valleys and the watersheds that divide them including those drained by the Souhegan and Contoocook Rivers, each a tributary of the much larger Merrimack River. Some of the hills are significant such as Mount Monadnock (3,165 ft (965 m)), which is part of the divide between the Connecticut and Merrimack River watersheds, and the already mentioned Temple Mountain. However, don't underestimate the smaller, lesser known hills. My eleven-village tour samples not exclusively, but nearly so, this region of hills and valleys found south of the more widely known White Mountains of central New Hampshire. From Sky Bridge or the Local Share, with plenty of caffeinated cycling fuel in your body, saddle-up and point your whip west. Just after the Sky Bridge Cafe, take a left. At this point, you're very close to the confluence of the Souhegan River, a tributary of the regionally significant Merrimack River and the locally valued Stony Brook. Cross the bridge over the Souhegan and take the first right. Here you'll begin your ascent into southern New Hampshire's hill country. A few hours later, as you approach Amherst, you'll roll-out of the same hills onto the former, glacial, outwash plain on which sits Amherst, Milford, and the eastern edge of Wilton among other towns and villages in the area. As you begin to ascend from the banks of the Souhegan River, grades will initially approach 15% but the majority of the climb, over about 3.5 miles including false flats and short descents, is far less steep. At a casual pace I climbed to the top in about 18 minutes. You'll gain a modest ca. 550 feet on this climb. Despite your proximity to the busy 101, just to the south, you'll already be getting hints of what lay ahead in southern New Hampshire's hill country. From the summit, you'll drop-down to the 101, turn left at the intersection, coast a few tenths of a mile, then make a right onto a country road. Over the next ca. 1.5 miles you'll gain another 400 feet in two back-to-back climbs. The second is impressive, for its steepness from the vantage of a bike saddle, especially with the initial climb already in your legs. From the top, you'll descend comfortably, possibly on a section of dirt road but I can't recall for sure, to the village of Temple, the second village on the tour. Temple was first settled in 1758. This early in your tour it wouldn't be advisable to drop-into the Birchwood Inn and London Tavern for a pint. But I would advise that you take a few photos and make plans to return to the village when you can stay longer. Scroll through the photos of the rooms available at the Birchwood Inn, they are impressive, cozy, welcoming, and a short walk to a "proper" British Imperial pint in the adjoining London Tavern. Temple is perhaps best known for the New England Glassworks Company (more commonly referred to as "Temple Glassworks"). The furnace and associated infrastructure from the factory were operational from just 1780 to 1783. Glassworks forged in Temple during this time are highly sought-after collectibles. From the village of Temple you'll pick-up state highway route 45 and head north. Not to worry, this short section of highway, less than six miles, does not attract high speed wackos like the 101. However, you will have to climb out of town, up-and-over the western slopes of nearby Mount Howard. Settle-in, this is hill country after all, they'll be much more climbing ahead. As you approach the 101, at the top of a steep descent where you can see the highway below, take a left onto a gem of a dirt road, smooth, wide, lightly traveled. It's a false flat most of the way to the next junction with the 101. When you get there, cross the highway (with care) and make a left into the cycle lane. This is the most dangerous part of the ride because you'll be sharing a busy road with high-speed motor-vehicle traffic. Stay as far right as possible as you ascend this part of Temple Mountain. The climb is less than a mile, about 5-6 % grade on average. The exit point, a right turn, off this cycling-unfriendly road is less than a half mile from the summit. When you reach the right turn off the 101, remember to return to normal breathing. I assure you, this short tour of the 101 is worth the risk for the opportunity to tour the villages and hill country west and north of Wilton. From the right turn off the 101, you'll enjoy a fast, flowy, paved road for a handful of miles before turning left onto a dirt track. Unlike the previous dirt section, the day I rode this section I encountered moderately deep ruts from water erosion as well as small patches of loose sand and gravel. Be prepared to ride your road or gravel whip like a mountain bike at times. If you're like me then you'll enjoy the challenge of riding this section at a sensible speed, but not too sensible. Note, part way down the initial descent off the paved road you'll come to a sharp left, take care not to overshoot the corner. To recap so far, from Wilton center to Temple you'll ride ca. seven miles with 1000 feet of climbing; then another ca. nine miles with 775 feet of climbing from Temple to Peterborough center. Peterborough is a popular destination for visitors and locals and the downtown area, primarily for tourists, is the center of that activity. Busyness aside, Peterborough offers a variety of shops set in an attractive New-England-style setting of bygone days. You won't be able to settle-in to every village on this tour, including the popular town centers of Peterborough and Milford, but you should at least do a roll through of the main tourist loop for future trip planning. If you're following my route and intend to complete the full eleven-village tour then it'll will be too early for lunch when you arrive to Peterborough. Regardless of your priorities, at some point you should stop-into Twelve Pine for a multitude of delicious sandwiches, salads, and other options. You might also enjoy Little Duck Organics, a grocer, or Aesop's Table, a wonderful combo bookshop and cafe. Be sure to save some time for my first recommended coffee stop at the Harrisville General Store. From Peterborough, you'll ascend the west bank of the Contoocook River onto a modest climb as you make your way out of the downtown area. Not far from the top of the climb, you'll make a right off the main road back into the forest. You're now on your way to Harrisville and the coffee-stop that I mentioned. As you make your way, you'll ride along narrow, lightly traveled, paved routes through rural, picturesque, hills and farmlands. Amidst the landscape scenes will be plenty of old stone walls to send your mind wandering back into New England's recent past when European settler's and their harness animals laboriously transformed continuous forests into patchwork farms. Although they'll be much more to see ahead, the section between Peterborough and Harrisville is certainly as scenic and peaceful as any other on the tour. Take your time, allow the natural smells and sounds to settle-in. Along the way, you'll encounter no hill climbs of any significance and no dirt sections (on my route). Shortly before climbing into the village of Harrisville, you'll ride for a few miles along the shoreline of Skatutakee Lake, the source of Nabanusit Brook. The Nabanusit converges with the Contoocook River not far from downtown Peterborough. We'll revisit the Contoocook one more time in the village of Bennington. At the end of Hancock Road, which parallels the north shore of the Skatukakee Lake, you'll turn right (north) onto Main Street in Harrisville. With less than a half-mile to cover before my first, suggested, coffee and food stop, I encourage you to unleash the athlete inside you and pedal hard up the 100 foot climb into town! You'll see the short climb into the village shortly after making the right turn off Hancock Road. The Harrisville General Store is on the left at the top of the climb. Many of the old mills from the town's earliest European settlement are on the right side of the road as you come into the village. Between the centers of Peterborough and Harrisville you'll pedal about 12 miles and climb a modest 1000 feet. In Harrisville, you'll be 27 miles into the route with 2700 feet of climbing already behind you. Stash your bike somewhere in front, next to, or perhaps even behind the General Store, there is no need to lock it in this part of the World. Once you're inside, allow your eyes to adjust to the bountiful food and drink options that surround you. Stare wide-eyed into the glass cases at both hardy and sweet options. Breath in the smell of quality drip coffee and imagine the satisfaction of a bottomless cup for a few dollars. Once you've performed a thorough-ish inventory of your options head to the counter and start ordering. If you're lucky you'll encounter a man with a strange ascent, that's the owner. I was told his dialectic roots sprouted in Zimbabwe. However, don't be dismayed if a lady or a non-funny speaking man greets you, I found only genuine smiles in this little shop perched above and beside "a unique, well preserved, 19th-century mill town" (more at Wikipedia). In fairness to those that performed the preservation, "a unique, well preserved, 19th-century mill town" really doesn't do the extent of the towns preservation justice. Coffee-in-hand from the porch of the General Store, so much has been preserved that a spandex-clad (or otherwise) visitor can easily hearken back to an era when "work", referring to the term as it applies to Physics, was produced exclusively in this and other mill towns by the "force", more physics, of gravity pushing water downhill. You'll absolutely want to come back for a foot tour of this town, including a visit to the original Harrisville train depot and the Cheshire Mills. In the meantime, check-out this Virtual Tour of Harrisville Village. Next-up on my clockwise tour of eleven villages in southern New Hampshire's hill country is the exceptionally sleepy village of Nelson, New Hampshire. It's so sleepy in fact that unless there is a contradance underway in the village town hall, a tradition dating back 200 years according to the locals, you could easily roll past without realizing you'd been there. As you make your way to Nelson you'll be reabsorbed by the land- and sound-scapes of southern New Hampshire's hills and valleys. The ride to Nelson from Harrisville won't take you long, it's only about five miles with 550 feet of climbing. Along the way you'll roll past Tolman Pond where, apparently, one of New England's first ski hills was established in the 1920s. At the junction of Nelson and Old Stoddard Road take a left into the village-center of Nelson for nostalgia and photos. When you're finished, return (back-track) to the junction and proceed east on Old Stoddard. My memory suggests that this is initially a smooth, no ruts and other inconveniences for tires and schedules, dirt road. After a short climb out of Nelson, you'll descend about four miles to state-highway 123 where you'll turn right towards Hancock, the next village on the tour. You'll follow the 123 for about six miles, nearly all descending, at which point you'll encounter a large white church and a post office on the left, both signs that you've entered one of New Hampshire's historic villages. Total climbing on this section is just ca. 580 feet, most of it on the initial climb out of Nelson that I mentioned. As any American might guess, the namesake of Hancock is the man that signed the Declaration of Independence with fifty-five other delegates to the Continental Congress. And namesakes withstanding, this short quote from Wikipedia paints a picture that should motivate you to visit and perhaps return again to the quaint village of Hancock, "Almost every building on Main Street in downtown ... is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as part of the Hancock Village Historic District. Hancock's Meetinghouse is home to Paul Revere's #236 bell, which chimes on the hour, day and night. The town does not have paved sidewalks, [instead] gravel paths [lead] from home to home." Hancock was first settled, by European invaders, in 1764. When you're ready to ride-on from Hancock, follow state-highway 137 out of town. Neither route 123 nor 137 present any concerns as far as traffic and proximity to fast moving vehicles. Neither road is heavily used and those that do use the road don't seem be late for their dinner reservation, which too often seems to be much more important than safety concerns for a nearby cyclist. Follow the 137 for ca. one mile then turn left onto Antrim Road. From this junction you're only 3.5 miles, with about 330 feet of climbing, from Bennington, the next historic village on my clockwise tour from Wilton and back again. If you've been scribbling down numbers and arithmetic then you may have noticed that "feet of climbing" per mile cycled has been declining in the last few miles of my description. That's because as you make your way east from Nelson you'll be riding out of southern New Hampshire's hills and into the region of the former outwash plain that I mentioned earlier in this blog entry. You'll descend off the last hill onto sands and gravels distributed by flowing glacial melt water, ca. 11,000 years ago, and later covered-up by invading plants, such as White Pine (Pinus strobus), as you approach Amherst. On Antrim Road (named for a village to the north) you'll find yourself in a space that should be familiar to you by now, the smells and sounds of southern New Hampshire's hill country. Ride on and enjoy the solitude. The village of Bennington is located at The Great Falls of the Contoocook River, the same river we encountered to the south in Peterborough. The Great Falls drop 70 feet in 1.2 miles (more details at Wikipedia). Attracted by the Great Falls, industrialists and their mills were already established in this town by 1782 not long after the conclusion of the American Civil War (1861-1865). Because I wanted to visit Bennington, a village north of both Hancock and Greenfield, I wasn't able to include a wonderful feature of the region known as the Hancock-Greenfield Bridge. On your future visits to the area, many I hope once you discover or perhaps rediscover, as I did, what you've been missing, I suggest making the bridge a part of one of your itineraries. The bridge lies about half-way, on a roughly east-west line, between the two villages in its namesake. All of the details that you'll need, are available at the Hancock-Greenfield Bridge Wikipedia page. From Bennington, my route heads south and then east to the village of Greenfield, about six miles with 400 feet of climbing on paved country roads. Amidst it's list of current and historical factoids, one fact, an accomplishment in this case, about Greenfield truly stands-out in my humble opinion. From Wikipedia, "Greenfield is home to the Yankee Siege, considered the most powerful ... trebuchet in the world. [The Yankee Siege] has participated in the annual World Championship Punkin' Chunkin' Contest in Sussex County, Delaware since 2004." Also from Wikipedia, "A trebuchet is a type of siege engine which uses a swinging arm to throw a projectile at the enemy." No doubt there is much more to see, eat, and drink in Greenfield, a town established in 1753 in part because of the distance to the nearest church and school and the "Monadnock hills" along the way, but don't let that stop you if your preference is to seek-out the "most powerful" pumpkin thrower, aka, the Yankee Siege! Once you're satisfied with your visit to Greenfield, roll east out of town on the main street. You'll spend only a minute or two on state-highway 31 before making a left turn onto a friendly cycling alternative. Enjoy the next six miles as you continue east towards the oddly named road "2nd New Hampshire Turnpike S". At the turnpike, a mellow road despite its name, turn right. The turnpike will take you directly into Mont Vernon, village number nine on my tour of eleven. Mont Vernon really is spelled without the "u" as in "Mount". But spelling aside, which they got wrong relative to its namesake, the town founders were apparently fond of George Washington and so they chose the name of his country residence, a plantation in Virginia, for the name of their town shortly after 1803 following a dispute with residents of nearby Amherst. There was a time when Mont Vernon was a favorite for travelers coming-up from the south, especially members of privileged societies from Boston. Hotels from that time, including the Grand Hotel, must have been a sight to behold, each of them sparing no detail for their elite guests. But sadly, none of them survived to the present (more details at Wikipedia). However, you can still view images of these old hotels on display in a museum on the second floor of the Town Hall, courtesy of the Mont Vernon Historical Society. If you need a snack before continuing on to Amherst, consider a quick stop at the Mont Vernon General Store, you'll roll past it, on the right, as you leave the village. Less than a mile south of town turn left on Amherst Road and follow this just three miles to the village center of the same name. Amherst, for white settlers, began as a land grant to soldiers that participated in King Phillip's War (1675-78), a war brought to Metacom (aka, "King Phillip"), then the leader of the Wampanoag Confederacy, by selfish puritans among others. An accurate telling of history aside, it's nonetheless fascinating to think that this part of New Hampshire was settled by soldiers from so far back in American history. At that time, New England remained a dangerous frontier for both natives and settlers. For an excellent, historically accurate, and unbiased account of the settlement of New England, including wars and other skirmishes, I strongly recommend Mayflower: the story of courage, community, and war, a book by Nathaniel Philbrick. Amherst has a wonderful central park, with a ring road around it, that is perfect for a short break, especially to take advantage of shade trees if you happen to ride on a warm day. The same park also provides an excellent vantage for capturing images of the park itself with historic buildings in the background. If you're feeling peckish, then I recommend a visit to Moulton's Cafe, on Main Street, they are apparently New Hampshire's original "soup bar" (see their webpage for more details). You'll find plenty more to eat at this location including a handsome menu of fresh sandwiches, baked goods, and groceries. When you're satisfied with your Amherst visit then pick the route back up and continue, just three miles on flat roads, to the last village on the tour. Hopefully, you'll have some time, before riding the six miles back to downtown Wilton, to drop-into the Union Coffee Company for your favorite espresso-based wake-me-up. They serve an excellent latte in a proper cup, visualize a soup bowl with a handle. Like Peterborough, Milford has a lot to offer the curious traveler. No doubt, if you need something you'll find it somewhere around the central oval (a ring road) found in this busy yet attractive, old New England-styled town. Milford's namesake was a mill, perhaps one of the mills still standing, built close to a ford over the Souhegan River, the same river we encountered not far from the Sky Bridge Cafe, in Wilton. Despite it's size relative to sleepy Amherst, Milford actually separated from Amherst, not vice versa, in 1794. I encourage everyone to visit Milford's Wikipedia page for a more thorough read of this communities rich history. For example, prior to the emancipation proclamation (1863) and the conclusion of the American Civil War (1861-1865), "Milford was a stop on the Underground Railroad for escaped slaves". With whatever gas you have left in the tank, supplemented by a caffeinated beverage from the Union Coffee House, from Milford head north from the ring road across the same bridge you came in on, over the Souhegan River, and turn left, to the west. From here you'll follow the Souhegan on a gently rolling, lightly trafficked, paved road. At the junction of North River and Purgatory Road take note of Fitch's Corner Farm Stand, you may want to return for fresh veggies on your way home. Take a left onto Purgatory Road then take your second right back onto North River Road and enjoy the last few miles back to where you started earlier in the day, downtown Wilton. If you were able to postpone your inevitable rendezvous with a hearty meal then you really should sample some of Jorge's, the owner of the Sky Bridge Cafe, locally famous paella. And although his espresso machine is modest by industry standards, Jorge's talent for preparing an espresso will nonetheless impress you and your taste buds. Depending on when you arrive to the Sky Bridge you may be able to sit in the shade, outdoors, with your feet up. Regardless of where you land when you step off your bike, be sure to let all that you've accomplished settle-in before you return to your busy life. Once you're back home and drifting-off into a well earned sleep, I anticipate that you'll dream about the hill country of southern New Hampshire; and when you wake, you'll consider plans for your next trip to Wilton for a day or part of a day of exploring the hills, valleys, and villages nearby. Strava links to other rides in the area from the Lava Monkey,

https://www.strava.com/activities/1184213358 https://www.strava.com/activities/1185596383 https://www.strava.com/activities/1187223189 https://www.strava.com/activities/1188751977 Native American name translations and other details from Wikipedia, Souhegan River: Algonquin, "waiting and watching place." Prior to European settlement, salmon, alewives, sturgeon, and eels all migrated to and from the river. The name for this river reflects a time when Native American's sat and waited, with nets across the river, to capture fish. Today, these fisheries are either gone (e.g., Salmon) or greatly diminished (e.g., American Eel), Merrimack River: Algonquin, "the place of strong current." Contoocook River: Abenaki, Pennacook Tribe, "place of the river near pines." Skatutakee Lake: No translation available. Nabanusit Brook: No translation available. Wampanoag: "People of the Dawn." For questions about this tour and any other inquiries please send me an email from my webpage. I'd enjoy corresponding with you. |

�

André BretonAdventure Guide, Mentor, Lifestyle Coach, Consultant, Endurance Athlete Categories

All

Archives

March 2021

|

Quick Links |

© COPYRIGHT 2021. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed